WHAT IS CAMP? The very definition of the term remains up for grabs in a way that isn’t the case for other artistic styles. Or is it a “sensibility” (as Susan Sontag called it)? Or an attitude, a commentary upon other styles or cultural constructs, thus a “meta” style? As a mode of social satire, most definitions agree that camp involves exaggeration, artificiality, over-the-topness. A more culturally specific definition sees camp as a feature of gay and lesbian culture when it satirizes heterosexual conventions and heterosexism. An even narrower definition tends to equate camp with drag, female impersonation, cross-dressing, or gender bending à la Annie Lennox, Madonna, or Elton John.

The notion of camp that I grew up with when I came out in the early 1960s was taught to me by a community of female impersonators, drag queens, and Jewish humorists. It was a camp that savagely mocked the rules and roles of straight society through gesture, language, voice, tone, pitch, fashion, exaggeration, and hyperbole. It was Miami Beach, art deco, Morris Lapidus’ Fontainebleau Hotel, Carmen Miranda, Desi Arnaz’ conga band, and Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films like Flying Down to Rio and Top Hat, which featured flamboyantly gay actors such as Eric Blore, Franklin Pangborn, and Edward Everett Horton.

As an eighteen-year-old budding lesbian, I was blown away by Jackie Jackson, Charles Pierce, and Dale Carter. They took me under their wings and taught me my gay heritage. I spent many nights at the Onyx Club in Miami Beach, absorbing their performances, afterward sitting in the shabby dressing room of Jackie Jackson (of the famous Jewel Box Review) watching him remove his makeup while cracking jokes with the others about the conventions of heterosexuality. So, you could say I took master classes in camp before Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” became the definitive word on the topic.

My experiences of camp gave me a real appreciation for the humor of Anna Russell’s parodies of Wagner’s operas, Lenny Bruce’s black comedy, Mel Brooks’ The Producers, Elaine May’s skits, Joan Rivers’ cutting-edge cynicism, and Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company (founded in 1967). As a graduate student at NYU, I naturally gravitated to Ludlam’s reinterpretation of the traditions of 19th-century theater in plays that he produced, directed, wrote, and starred in (often in female as well as male roles). He was a master of travesty: Ludlum coined the term “avant derrière,” creating parodies of such familiar genres as the dime novel (The Mystery of Irma Vep), film noir (The Artificial Jungle), and opera (Camille, Der Ring Gott Farblonjet).

Camp is the revenge of the oppressed: gays’ version of Jewish parody with its mocking Klezmer clarinets. Perfect examples of this are Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera parading through the mean streets in the cast-off rags that the affluent consigned to the garbage heap—truly gay Camp with a capital C. [Editor’s note: Even the question of whether camp should be capitalized remains unsettled. We went with the lower-case option.]

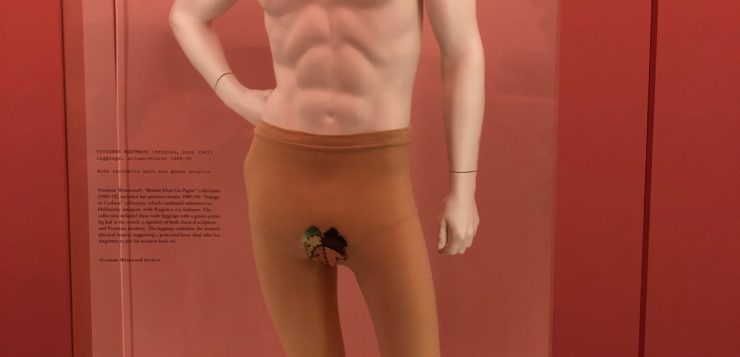

Currently, what passes for camp in popular culture is sadly lacking in this innovative critique. In brief, camp has gone mainstream, and there’s no better example than the current mega-exhibition titled Camp: Notes on Fashion at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, mounted by its Costume Institute, which attempts to piggy- back on camp’s gay legacy during the Stonewall 50 anniversary. The Met’s spectacle is a cultural and sartorial tour through the history of fashion containing 250 objects, of which 170 are garments. Some of the rest are pictures of people like an 18th-century French nobleman (Chevalier D’eon) dressed in drag (see p. 28) and Oscar Wilde in various poses. Most of it is an awfully long way from authentic camp. Instead, it is a shrewdly selective assemblage of artifacts of high fashion worn by the moneyed classes when it has gone over the top or toyed with gender reversals. To its credit, the show takes its subject seriously. Thus, if one definition of camp is “failed seriousness” (favored by Sontag), then one could say that this exhibition is itself an example of camp.

What camp is not is the rich performing rituals of wealth. Camp by its nature cannot be practiced by the rich and powerful—or, for that matter, imprisoned in a museum. (Sponsors of the exhibit include Gucci, Conde Nast, and Vogue.) Instead, it is the transgressive art of people considered by the one percent as nobodies mocking their “betters.” Nonetheless, gay icons like Lily de Gramont (friend of Marcel Proust, and Natalie Barney’s lover) would have enjoyed the spectacle. Elsie de Wolfe would have cartwheeled her way through the party startling the ensemble, and Romaine Brooks would have howled with laughter to see fashion designer Thom Browne planting her portrait of Una, Lady Troubridge, on an expensive designer jacket.

The artist Philip Core in his book Camp: The Lie That Tells the Truth (1984) defined Camp as “the heroism of people not called upon to be heroes.” Camp is easy to imitate, but then there are the originals, such as the activism of Marsha P. Johnson and others who supposedly had nothing and were worthless to straight society, the celebrated, and the privileged. But times have changed, and the camp I cut my teeth on as a young lesbian is out of fashion. Today, being gay is just a fact of life. True camp is serious fun at a time when the degenerate authorities are trying to push us back into the dark closets of yesteryear. As Josephine Baker said: “if I’m going to be a success, I must be scandalous.” I think now is the time to re-envision the possibilities for camp, to see it with new eyes, and to give it new meaning for the current generation of gays.

FASHION, as all good gay camp aficionados know, is the height of art as artifice, whimsy, frivolity, and satire. It is the vanity of the human ego splashed across the pages of fashion magazines, newspapers, television, and social media worldwide. The Costume Institute’s annual red-carpet event in May, fund-raising millions of dollars, was the talk of the town. There were exclusive openings for the wealthy, famous, and privileged, which in turn were catnip for the mainstream press.

was part of a blackmail settlement with King Louis XVI.

The exhibit opens with the words “Se Camper” (“to flaunt” or “to posture”), the French origin of the English term, which has been in use for centuries. The show is in two parts. The first part moves through four eras personified by Versailles, Oscar Wilde, Christopher Isherwood, and Susan Sontag. It kicks off amusingly, like the Netflix’s series Versailles, in the 1600s at the court of Louis XIV. Jan Versweyveld, the Belgian theater designer who created the rabbit warren of rooms that contain Camp, opines that gay icon Philippe, Duke of Orléans, “didn’t know he was inventing camp, but he did!”

In the space dedicated to Sontag, pages from “Notes on Camp” are on display, and visitors will hear the kitschy sound of a typewriter keyboard clattering away, while overhead fashionably dressed mannequins in colored glass enclosures look on. Curator Versweyveld states: “To me, light and space are the same thing; they come together.” As an art historian and curator, I have no idea what this statement means. Nor do I think the soundtrack of Judy Garland singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” helps to illuminate the items on display. Versweyveld also confided: “I’m not an experienced exhibition designer, but being able to think in that unity helped.” Lamentably, it does not excuse an installation that looks more like a series of colored cellophane display boxes featuring models wearing various high-end designer brands.

The second part of the show sets out to present contemporary manifestations of camp, as shown by a multitude of extravagant designs that could have been taken from a fashion runway catalog. The curators are to be commended for highlighting a few cross-dressing women: Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, et al. But, it is equally important to acknowledge those who were acting out in sleazy cabarets and theaters in the Village and on the streets. As philosopher Jack Halberstam points out: “Camp is very pointedly a critique, not just of the fashion world but of the cultural appropriation that the fashion world engages in when it basically is mocking and stealing from Latinos and black gay men, and then calling it high fashion.”

As a lesbian and as a fan of camp, I think Camp raises some troubling questions. Camp at its most authentic exemplifies the radical work of inserting the visual presence, the physical manifestation, of mongrelized and marginalized groups. It is subversive; it mocks; it is not a Vogue-curated fashion show. What’s missing is the art of Jack Smith, the artistic armor of Linda Stein, the screaming leather-encased heads and bodies of Nancy Grossman, the street performances of Marsha P. Johnson, and the Theater of the Ridiculous as scripted and performed by Charles Ludlum.

Camp for the gay community has always been subversive and anti-establishment. It originally was the arsenal of the criminal, the sinners, the mentally ill, the transgressive who refused to be boxed in and caged by bourgeois society and aristocratic pretentiousness. Gay people were outlaws and regularly put in jail and deprived of their rights by powerful people. Very little on display at the Met has anything to do with this side of camp.

Fashion designers and branding people are continually attempting to redesign the world by populating it with various flavors of the season: African, Middle Eastern, or whatever look grabs their fancy for big bucks. The New York Times publishes article after article digesting and regurgitating their public relations blitzes on the nuances of camp, debating camp, and selling camp. The press even mainstreams John Waters, the “prince of puke.” Who would have thought that, in the 21st century, camp would waltz up the red-carpeted steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wearing designer bling, dressed as a crystal chandelier and advertising a new line of a pop star‘s clothing?

In June, more than four million people filled the streets of Manhattan to celebrate the 50th anniversary of gay pride. But how radical is having MasterCard, T-Mobile floats, and other symbols of corporate sponsorship flying overhead in a celebration that once was about resistance to and disruption of corporate colonizing? Pride 50 celebrates fighting for equal rights under the Constitution—rights that are now under full-scale attack by the current administration in Washington. The mainstreaming and containment of camp are symptomatic of a larger mainstreaming of LGBT culture that has taken its toll on the spirit of activism without which our rights hang in the balance.

Cassandra Langer, a freelance writer based in New York City, is the author ofRomaine Brooks: ALife (Univ. of Wisconsin Press).