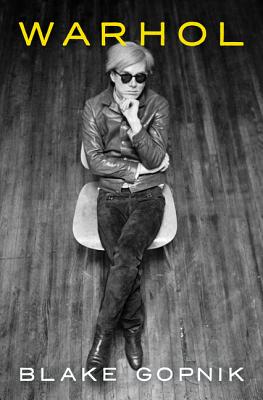

WARHOL

WARHOL

by Blake Gopnik

Ecco HarperCollins

976 pages, $45.

ART CRITIC Blake Gopnik, who has a doctorate from Oxford, wears his scholarship very lightly—sometimes too lightly—in this comprehensive biography. He interviewed 260 people, consulted 100,000 documents, and had the contents of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh at his disposal. The resulting book, Warhol, recounts Warhol’s life in chronological order in fifty chapters, each introduced by an often lovely black-and-white image.

Gopnik begins with Warhol’s poverty-stricken childhood, when he began taking photographs with his family’s Brownie camera and showing comic strip films on a hand-cranked, home-movie projector, which his mother scrimped and saved to purchase. He digs deeply into the archives to discover precisely what Warhol learned in his high school and college art classes, and what art shows he visited, consulting exhibit catalogs to see what Warhol saw and how those works influenced him. He describes each of Warhol’s many apartments and Factory locations in New York, his roommates, and his early years as an illustrator, his rise to fame and his eventual selling out, in Gopnik’s view, to commissioned work and occasional television appearances. He has particularly harsh words about Warhol’s 1986 appearance, as himself, in an episode of the popular comedy series The Love Boat, which became a multimedia event that Warhol described as the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable.”

Warhol highlights the line that connects the artist to Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists. In fact, Warhol was originally called a neo-Dadaist. In one of its many digressions, the book describes at length the French artist Yves Klein, perhaps best known for his 200 blue monochrome paintings, and their influence on Warhol. Another major influence was his “admitted hero,” the popular social realist Ben Shahn. Warhol’s blotted line technique was based on Shahn’s “fractured, lightning-bolt line.” Shahn had been influenced by Paul Klee, who was himself a big influence on Warhol.

While mostly concerned with his career as a painter, the book also delves into Warhol’s other ventures, notably filmmaking, writing, photography, and music management. One of Gopnik’s insightful remarks concerns the four-minute Screen Tests in which the subject—usually a notable person—would be filmed staring at a screen: “The Screen Tests give us our first taste of the passive sadism that Warhol became famous for as his Factory scene moved into high gear.”

Many of Warhol’s major early exhibits are nicely described, such as the 1964 exhibit of the Brillo Box sculptures at the Stable Gallery. Gopnik’s turned up far too many gems to mention here, so let me stick to two. There was an apparently one-off fan club newsletter, Andeeeeee monthly (Wee Hope) GAZETTE (capital letters in the original), which the Smithsonian has made available. An unpublished interview that was supposed to appear in the Spring 1966 issue of the Yale Record quoted Warhol as stating that “I always wanted to be a girl.” It is worth noting that Gopnik spends a great many pages describing, often in excessive detail, every man who could conceivably have been described as Warhol’s boyfriend.

Warhol’s personality will probably never be revealed in its entirety, and Gopnik has pieced together a wildly complicated man who went from being a “sweet little gay guy who worked like a dog,” according to a Harper & Row editor, to a self-consciously cultivated enigma, a modern-day court portraitist of the many socialites in his orbit, and a world-class manipulator. Toward the end he showed a gentler, more easygoing and kinder side in the year leading up to his death.

There is no shortage of qualifications that one might raise about this doorstop of a book. The big one is the absence of any references, which are available only online, either as part of the electronic version of the book or on the publisher’s website as a 740-page PDF. Gopnik’s writing style can also be off-putting. It seems at times that he’s trying too hard to strike a casual or hip style, as when he constantly uses verb forms like “got published” or “got painted” or when he addresses the reader directly as “you.” That said, this book is a feat of Warhol research that offers new insights into a widely studied artist.

Martha E. Stone is the literary editor of this magazine.