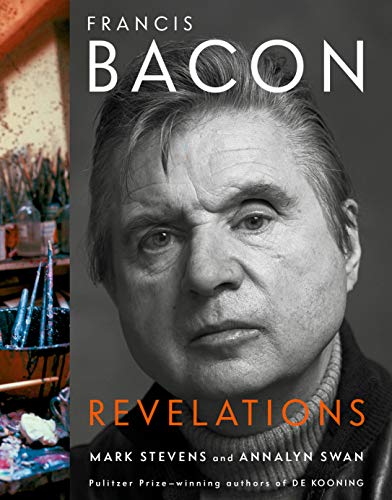

FRANCIS BACON: Revelations is an expansive biography of one of the world’s most discussed painters of the 20th century. Art critics Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, authors of a biography of Willem de Kooning, carefully examine Bacon’s life, art, and times, showing the philosophical grounds underlying his disturbing pieces.

Bacon was born in Ireland in 1909 to a family with aspirations of nobility. His father, formerly in the British military, dealt in horses and had many of them stabled on his estate. As Bacon suffered from asthma as a child, all this animal hair aggravated his condition. Uninterested in horses, sports, and other “manly” pursuits, Bacon frequently attracted his “tyrannical” father’s anger, who apparently vented it in shocking ways, including having his grooms beat the child. Bacon would later report that the grooms also assaulted him sexually. At one point he traveled to Berlin with a sexually adventurous family friend; Bacon would later claim his father “sold” him to this friend.

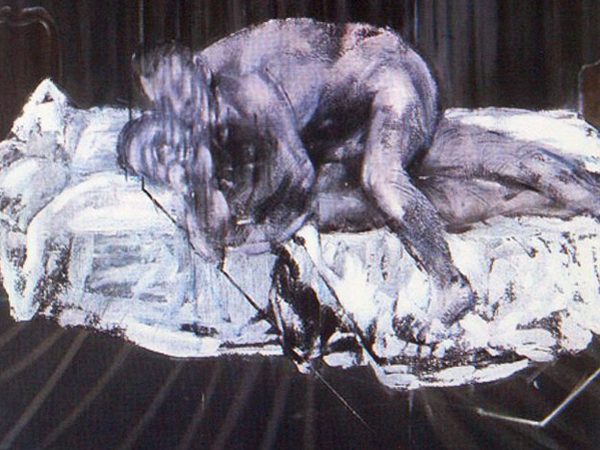

Escaping as a young man to London and Paris, Bacon began a brief career as a designer. He attracted the interests of older, closeted men, who helped him out financially and career-wise. When money was hard to come by, he would take out classified ads looking for these types of men. Eventually he started painting, producing those unsettling works of popes screaming, people with mouths full of sinister teeth, and grotesque figures reminiscent of the Furies of Greek mythology. Stevens and Swan consider his Three Studies for a Crucifixion “arguably the most disturbing painting in twentieth-century art.” When it was first displayed in a gallery, many visitors would walk out immediately upon seeing it. He would also occasionally paint scenes such as Two Figures featuring two men in a moment of passion. Bacon’s dealer thought this was “his finest work,” but due to the conservative, anti-gay climate of the times, he was unable to display it openly or find a buyer for it.

For many people, these paintings seemed to expose the true, animal nature of humanity, which, after the devastation of two world wars, could no longer be viewed as civilized or a force for good. This suggestion makes sense in light of Bacon’s deep knowledge of and interest in the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who argued that Christianity was a religion of slaves giving the weak an unjust way to rule over the strong, a belief system that papered over humanity’s darkest desires. Bacon was a self-educated thinker as well as a self-taught artist, who had several copies of Nietzsche’s work on his night table. Nietzsche may also have been homosexual, making for an interesting connection between him and Bacon.

Bacon’s romantic life was as provocative and distressing as his art. One lover died on a Paris hotel room toilet the night of Bacon’s French retrospective. Bacon claimed to have met another lover when the man broke into his studio. At least two beat him frequently, which Bacon seems to have relished. Stevens and Swan make clear that this was not ritualized S&M but rather bloody attacks that left bruises and missing teeth. Before leaving his home for the day, Bacon often wore makeup emphasizing his bruises. In what may be a throwback to his childhood encounter with the grooms, he enjoyed pushing his lovers to violence. He certainly liked provoking the establishment, as shown by his lone booing of Princess Margaret’s singing at a high-society function. He often wrote apology letters to friends the next day for his behavior the night before. With many black-and-white photographs of locations and friends and color reproductions of his work, this biography captures the complexity and talent of a major artist.

Charles Green, a frequent reviewer for The G&LR, is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.