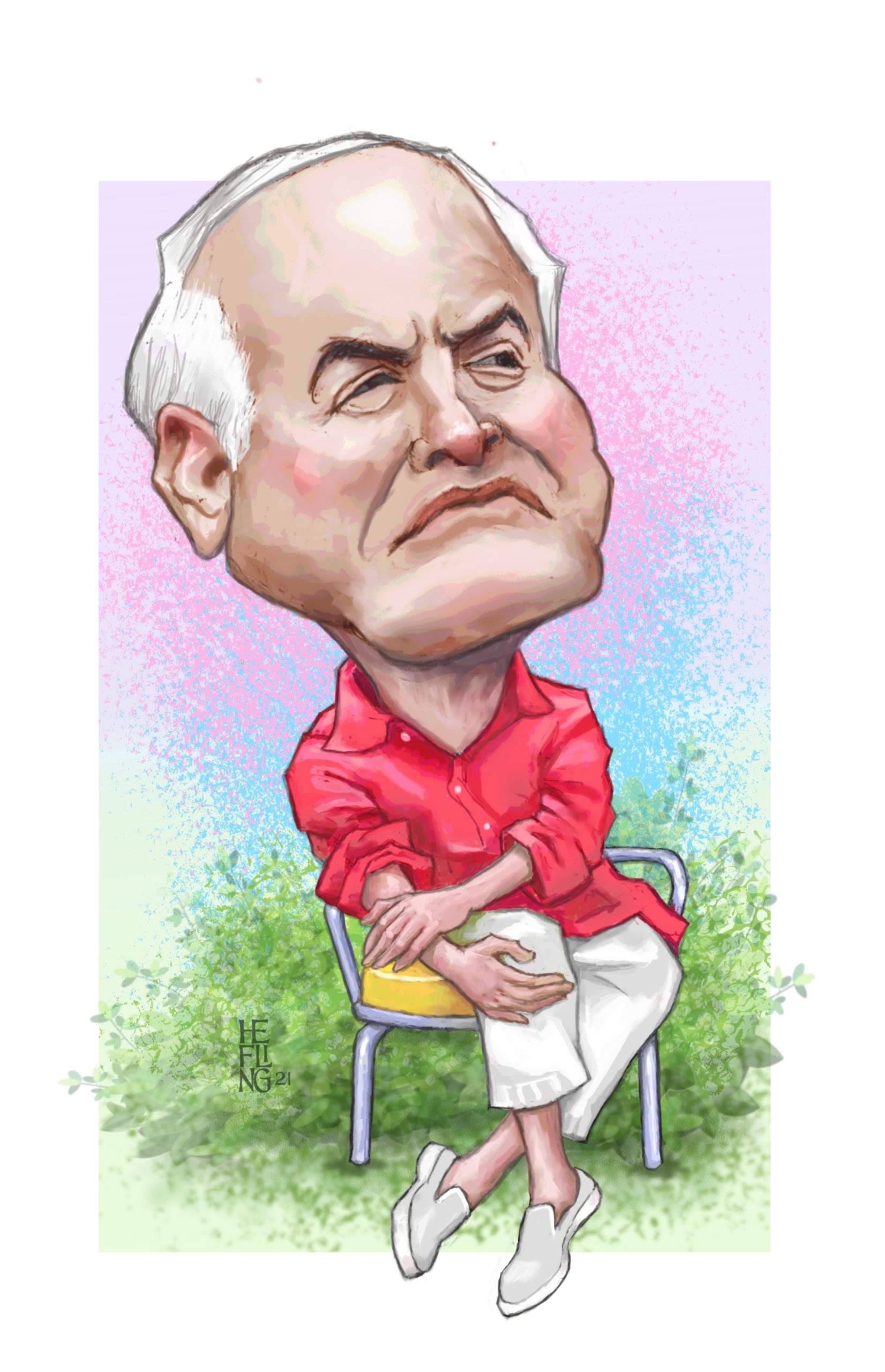

MOST READERS of these pages will probably identify James Ivory as the director of those sumptuous film adaptations of E. M. Forster’s novels—Maurice, Howards End, A Room with a View. Some readers will also know that Ivory formed a decades-long personal and professional partnership with the Indian producer Ismail Merchant to make those films. Yet few readers may know about Ivory’s small-town-boy-makes-good story, or about how he has lived his life as an openly gay man for most of his ninety years, starting at a time when that wasn’t easy. And even fewer readers may be aware of the range of good, great, and mediocre films he made as an extremely hard-working director for 65 years.

Now Ivory has opened doors to all those vistas by publishing Solid Ivory, a collection of autobiographical memoirs. This is a mélange of a book—with sections of different lengths and types, ranging from long letters written to specific correspondents to old New Yorker “Talk of the Town” pieces to beautifully written portraits—with much of the material designed to set the record straight about Ivory’s life.

Solid Ivory opens with “Growing Up,” a collection of pieces about his boyhood in Klamath Falls, Oregon, followed by “Queer as Jack’s Hatband,” which includes snapshots from his youth and young adulthood. Here Ivory provides details about the history of his family on both sides for several generations, back to his great grandfathers, only to reveal that he was adopted. This is not his biological family, and he reveals nothing about his biological parents, so clearly he’s not looking for some kind of family trait or genealogical thread.

The other main theme of this section of the book is Ivory’s attempt to describe the nature of his relationship with every young man he ever longed for or lusted after, starting with the mutual fellatio he had with his best friend at age seven, which was interrupted by his mother, and on to his sexual escapades in high school, college, graduate school, and shortly thereafter. Simply lying beside one high school mate gave young Jim an orgasm. Years later, two of these young men revealed that they also wanted to have sex with him but were afraid to act. What’s even more remarkable is that Ivory includes photos of all his crushes and conquests—snapshots, yearbook pictures, and so on. Together these episodes offer a sense of what it was like to grow up gay in Ivory’s milieu in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, a fearful time when gay life for young men was entirely furtive.

Also covered in amazing detail is Ivory’s years-long “affair” with the travel writer Bruce Chatwin. Ivory himself questions the use of the word “affair,” since their relationship was almost exclusively sexual. He even remembers how rancid Chatwin’s dick smelled when he hadn’t bathed for several days. Ivory seems almost cruel in inserting Chatwin’s wedding photo into this granular account of the many times he and Chatwin had sex, and where, and how.

Another tell-all section is Ivory’s score-settling with Luca Guadagnino, the director of the film Call Me by Your Name. The screenplay for the movie, for which Ivory won an Oscar, was written on spec, without advance payment. It was part of his general agreement with Guadagnino to codirect the film and return for a season of work in his beloved Italy. Then, weeks before production was to begin, Ivory was dumped. He was even told there would be no hotel room for him on the shoot. Two actors he had committed to for the film—Greta Sacchi and Shia LaBeouf—were also dumped. Neither Guadagnino nor his staff called the actors or their agents to let them know all this. Nor did the director ever call or write Ivory to explain why he would not be codirecting the film.

But the coup de grâce in this take-down of Luca Guadagnino is Ivory’s citation of the page in his script in which he depicts the love scene between the two young heroes. After a summer of increasingly heated anticipation, the two are finally in bed together, naked. Though the actors’ contracts prohibited frontal nudity, Ivory’s direction for a shot of feet on shoulders would have provided a vivid indication of sexual intercourse. Instead, Guadagnino panned away from the two in bed to an open window, as many of us groaned at this lapse into a cliché as old as the many 1940s and ’50s Hollywood films in which it was used.

Fortunately, the spirit that shines through most of Solid Ivory is neither score settling nor salacious. Instead, this is a profusely illustrated account of how a gay man from the provinces met the people who would help him to become the artist he was destined to be, how he accomplished that work, and what he thinks of his life, looking back.

First, he pays homage to the great Indian director Satyajit Ray, whom he calls Maestro. Being a guest on Ray’s set and watching him direct, day after day, taught Ivory what a director actually does. On his first feature film, The Householder, and on the next four films he made in India, Ivory was able to use Ray’s cinematographer and much of Ray’s crew. When he had trouble editing The Householder, Ray stepped in and recut it. Most importantly, Ray was at the center of that Indian nexus that introduced Ivory to his two great collaborators, Ismail Merchant and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. With these two he formed the triumvirate behind most of his films, both the hits and the misses. For decades the three of them lived in the same apartment house in New York City or in the same house in upstate New York. His portraits of them are among the most engaging parts of this book.

First, he pays homage to the great Indian director Satyajit Ray, whom he calls Maestro. Being a guest on Ray’s set and watching him direct, day after day, taught Ivory what a director actually does. On his first feature film, The Householder, and on the next four films he made in India, Ivory was able to use Ray’s cinematographer and much of Ray’s crew. When he had trouble editing The Householder, Ray stepped in and recut it. Most importantly, Ray was at the center of that Indian nexus that introduced Ivory to his two great collaborators, Ismail Merchant and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. With these two he formed the triumvirate behind most of his films, both the hits and the misses. For decades the three of them lived in the same apartment house in New York City or in the same house in upstate New York. His portraits of them are among the most engaging parts of this book.

In particular, his portrait of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala is as deft as one of her own wonderful short stories. From 1960 until her death in 2013, she was not only Ivory’s scenarist but also his “preceptor,” the “older woman” from whom he learned about life, even though she was only a year older than he was. To convey his deep indebtedness to her, he chooses a few moments and scenes to highlight the varied colors of her character. These are enough to suggest the many ways that she stimulated, challenged, and finally gave resonance to his life, from 1960 to the present.

The most difficult job Ivory faces in the book is how to portray Ismail Merchant, his life and professional partner for over forty years. Though there are sketches of Merchant throughout the book, the lens tightens in the “Portraits” section, which zooms in on his incredible poise and aggressiveness and self-confidence, whether when raising money for their films or when handling their publicity. Without Merchant’s drive, there would probably have been no Merchant Ivory Productions, the company they formed. Nor would Ivory have gotten to direct the two dozen films that he did. And many of those films might have foundered halfway through their shoots were it not for the incredible curry dinners that Merchant would cook by himself, staging a feast to smooth the frictions that develop on any film set. As in many partnerships, the two men often drove one another crazy, but they never gave up on keeping themselves together.

Ivory is also candid about the sexual aspect of their relationship over four decades. Merchant was “highly sexed” and often sought out new sexual partners. Sometimes Ivory also had a sexual fling. On some occasions, Merchant and Ivory would have shared sex with their new conquest. But from their first meeting in 1959 to Merchant’s death in 2005, their first allegiance was to one another, not only in their professional but also in their personal and sexual lives.

Two other sections of this book deserve a spotlight. Ivory paints a long and marvelous portrait of the great actress Vanessa Redgrave. He reports how he first tried to cast her in The Bostonians while she was suing the Boston Symphony for terminating her narration contract because of her support for the Palestinian cause. She says Yes at first, then No, as Ivory courts other major stars who say No, then Yes, then change their minds again. He ended up with Vanessa Redgrave. In reporting on his relationship with Redgrave over the years, he indirectly sheds a sharp light on the casting process in films, on finding locations to film, and on the scheduling changes that continue crazily until the camera finally begins to roll.

Ivory reveals “What I Do” in a section that focuses on how a film director assembles a forest out of all the individual trees that have to be brought together in making a film. Actors are deep but not wide, Ivory says, while directors are wide but not deep. So one must trust actors to do their thing until they start to go terribly wrong and must be corrected. Directors must think horizontally, expanding their attention to encompass everyone on the set, all those actors and crew members who are thinking and working vertically. So he tries to hire the best actors and designers and camera crew he can find, then lets them do their thing. Though Ivory’s description of his process may be oversimplified, it does explain why he is known as “an actor’s director” and why the designers on his films have won so many awards.

Solid Ivory is not without some dross. Who needs portraits of people like Susan Sontag, Kenneth Clark, or George Cukor, all of whom Ivory only encountered once or twice? Why show himself a “star fucker” when he himself is celebrity enough? Why spend fifteen pages on a dinner party at an English country house that Prince Charles happened to attend or on an unmemorable dinner in India, however star-studded, that took place years ago? The inclusion of these pieces makes one wonder if Ivory the writer has forgotten the lessons he learned as a director. Sometimes one must leave some of one’s favorite scenes on the cutting room floor because they impede the flow of a film.

Still, this is a remarkable book. To anyone who ever knew or worked with James Ivory or loved his films, here he is, warts and all—fussy and fastidious and snobbish, gutsy and generous, aggressive in trying to live the life he wanted and brilliant in transforming words and ideas into gorgeous images flowing across the screen. Here also is his testament to how difficult and how important it is just to keep working year after year. Whether the product was the brilliant Remains of the Day or the forgotten Hullabaloo over Georgie and Bonnie’s Pictures, Ivory shows us that the creative journey is what one remembers rather than the tangible result. We just “carried on” making films, he says, without stopping for long to bask in their success.

Cal Skaggs. a producer with over thirty dramas and documentaries to his credit, is president of Lumiere Productions in New York City.