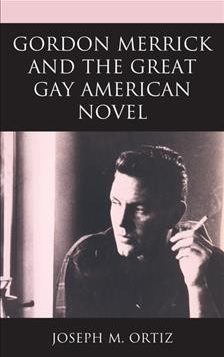

Gordon Merrick and The Great Gay American Novel

Gordon Merrick and The Great Gay American Novel

by Joseph M. Ortiz

Lexington Books. 359 pages, $120.

As for the mansion in New Jersey, the rich grandmother, the little car—the creator of this fantasy knew whereof he wrote. Gordon Merrick was born into a prominent Philadelphia family whose ancestors had served as trustees for the University of Pennsylvania. But after growing up on the Main Line in a house with a butler, he broke with family tradition by going to Princeton. He was not only well-born but movie-star handsome. At Princeton, he got such rave reviews for his performances in student plays that he dropped out of college and moved to New York to pursue a career on the stage, where he got a part in George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s famous Broadway hit The Man Who Came to Dinner (after an audition with Hart that apparently included a casting couch). But bored with having to repeat the same lines night after night, Merrick left the cast just before the play was made into the movie with Bette Davis, something that might very well have sent him on another career path altogether. But he wanted to write. A friendship with Glenway Wescott led to his meeting writers like Christopher Isherwood and W. H. Auden—until he left his job with The New York Post to work for the OSS (the predecessor of the CIA) as a spy in occupied France.

His first novel, The Strumpet Wind, was based on his experiences as a spy working for the OSS in occupied France during World War II. The Strumpet Wind came out at about the same time as Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar and John Horne Burns’ The Gallery. Reviewed in The New York Times, Merrick was on his way as a “serious novelist.” But his next books did not fare as well. His publisher, William Morrow, declined his second novel, The Demon Noon, which came out in France instead. Nor did Morrow want The Vallency Affair. (Neither of these is a gay novel, though there are gay subplots.) In 1958, Morrow did publish The Hot Season, but it was a flop, at which point Merrick moved to the Greek island of Hydra, and spent the next ten years as the doyen of a society of writers, alcoholics, and expatriates who bought and fixed up homes on the then unspoiled island. But after a decade in Hydra, all Merrick had to show for himself was four unpublished novels and some short stories. So he decided to write about the subject he had treated only glancingly in his previous books: homosexuality.

Merrick was an anomaly among homosexuals. He disliked gay bars and neighborhoods—Midtown is where Merrick settled when he moved to New York, because he didn’t want to live with all the “fairies” in Greenwich Village. He found San Francisco provincial and uninteresting. Yet when he lived briefly in California, he was several years into his second long-term partnership with another man, Charles Hulse, a professional dancer he’d met in Paris at the Folies Bergère. Before that he’d lived for ten years with a very handsome Air Force pilot that he met at the funeral of another pilot with whom he’d previously fallen in love. Merrick seems to have wanted to live life not as a “fairy” but as a man who—you’ve heard the phrase—happened to like sex with men. However, in his case it was much more than sex: it was romance, partnership, commitment, a shared home—what we would call gay marriage today. And that was the story he started to tell in a trilogy whose first volume was The Lord Won’t Mind.

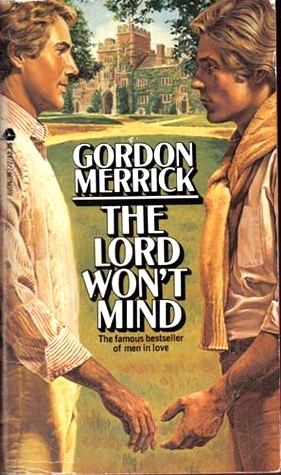

After The Lord Won’t Mind was turned down by William Morrow because of its subject matter, the manuscript was acquired by Bernard Geis, who’d published Valley of the Dolls. Merrick’s novel came out in 1970. Like Valley of the Dolls, it was a bestseller, remaining on the New York Times list for sixteen weeks. A few years after that, Geis’ publishing house folded, and Merrick was shunted off to his paperback publisher, Avon Books. After that, his novels were always paperbacks—a huge distinction, since paperbacks were not reviewed in The Times.

The cover of The Lord Won’t Mind, and later novels, was the work of the artist Victor Gadino. whose work—beautiful young men on the campus of Princeton, or in the south of France, or the Greek islands—not only pictured places where Merrick had lived but advertised the books’ view of gay life. The novels were inseparable from their covers, so much so that people felt that there was no reason to actually read the things.

Who did read Merrick’s books? Not his agent, Merrick eventually realized, or even his editor at Avon Books. But thousands of fans did. Sales figures are sprinkled throughout Joseph M. Ortiz’ new biography, Gordon Merrick and the Great Gay American Novel. One refers to over a million books sold. They did well in France and England. French critics considered Merrick a “serious” novelist. It helped that Merrick was fluent in French (one reason the OSS hired him), and so did the fact that he was critical of his own country’s shortcomings. His early books, which Ortiz calls “protest” novels, were about the cruelty of both sides in World War II, American racism, and class prejudice. The new ones were about sex, however, because Merrick felt it was important that people know what gay men did in the sack. Merrick took pains to get his sex scenes just right, as Ortiz discovered after going through Merrick’s papers in the Princeton library. This, of course, opened Merrick up to the charge of writing soft-core porn.

Gore Vidal claimed that he’d been blackballed by the critics after publishing The City and the Pillar because of its subject matter. Whether or not that’s true, this is sort of what happened to Merrick after The Lord Won’t Mind. Until then, the theme of homosexuality in his novels had been a minor one, his lead characters always straight, but with The Lord Won’t Mind the struggle of a gay man to find happiness became the main subject. Writing about his own life liberated Merrick, as it would so many writers in the following decade. Four years after ignoring The Lord Won’t Mind, the Times reviewer praised Patricia Nell Warren’s The Front Runner as “the most moving, monumental love story ever written about gay life.” It was only the first in an efflorescence of gay novels in the late 1970s.

The main thrust of Ortiz’ book is to answer the question: Why did Merrick’s novels get so little respect from critics? The answer is to be found in the meticulous research he’s done. There is not, for anyone interested in the literary aspect of gay liberation, a page or paragraph without interest in this gracefully written study. “The purpose of this book,” Ortiz writes, “is not to argue that Gordon’s novels are masterpieces that have been unjustly banned from the upper echelon of gay literature.” Nor is it, strictly speaking, a biography of Gordon Merrick. It’s the story of a book; but because it’s this book, it is about gay liberation. It reminds us that the latter was not just Stonewall and Pride parades; it was a cultural battle, conducted via movies, TV shows, journalism, novels, and plays. And you could argue it really began in the theater.

The idea of giving his gay characters a hopeful future was something Merrick had dreamed of since reading E. M. Forster’s novel Maurice, the book Forster chose not to publish during his lifetime (which Merrick read in manuscript). At its end, the two lovers are about to leave England to find a happy life together, far from the society that proscribed their love (exactly, you might say, what Merrick did in his own life). Crowley’s play was criticized by many for painting too dark a picture of gay men, while others felt it was brilliantly honest—a debate that goes on to this day. And it’s tempting to see The Lord Won’t Mind, which appeared two years later, as a reply to Crowley’s work. But Merrick’s novel was no more inspired by Crowley’s play than it was by Stonewall, Ortiz points out. Merrick had begun writing it in 1967, before both events, and he was already showing it to publishers in 1968, when he was living on the Greek Islands. And yet, Stonewall, Crowley’s play, and Merrick’s novel were responses to the same forces that were moving American culture forward, at least in its willingness to admit that homosexuals were human beings.

What’s so well done by Ortiz is his re-creation of the whole milieu in which all this happened. He may have set out simply to tell the story of a book that meant a lot to him as a young man—afraid that purchasing it would reveal his sexuality to the cashier. But his book ends up being a fascinating history of the arguments over just how gay people were to be portrayed.

AS I WRITE, the media are running stories about the delicacy of getting the word out about monkeypox without stigmatizing its major target group, gay men. People are even nervous about the term “monkeypox,” since it seems to turn victims into out-of-control primates screwing each other. But what gay men do in the sack has always made society nervous. Until the ’60s, gay fiction writing, save for a few isolated novels (Finistère, City of Night), had been confined to mass market paperbacks liable to face prosecution under the laws against sending anything obscene through the mail. Homosexual novels were either commercial pornography or literature; and when the latter, they had to have a tragic ending. In the original ending of The City and The Pillar, the hero murders the man he loves. (Vidal later revised the ending, changing the murder to a rape.) Merrick’s two men end up committed to one another. Yet The Lord Won’t Mind irritated many gay critics. It was too romantic, too escapist, too glamorous, too much like soft-core porn. After Merrick began writing about gay men and gay sex, he was no longer considered a “serious” writer. He simply sold a lot of books.

Was it prudery? There are, of course, the sex scenes. In his interview with Michael’s Thing, Merrick said: “it was important that straight people know exactly what gay men did. Otherwise, straight people would fill in the gaps with their own distorted, horrifying, stereotypical fantasies.” Others felt differently. At a party in London, Edward Albee “lost his temper and screamed at Gordon: ‘Merrick, how dare you write all that crap! You have an eight-inch cock and I have an eight-inch cock but we don’t have to write about it, do we?’” Afterwards, Merrick professed to have been confused by Albee’s reaction to his novels. “I didn’t know what it was about,” he said. “It was as if I were giving away trade secrets.” But Noël Coward was of the same mind as Albee. “My dear boy, that isn’t done,” he supposedly told Gordon. “We don’t talk about it.” What was it? The mechanics of gay sex.

At the time, gay intellectuals seemed to be divided into two camps: those who urged us to put sex back into homosexuality, and those eager to show that we were not defined solely by what we did in bed. Merrick’s agent exemplified the split when one of his Avon paperbacks was to be serialized, and she chose to send it to Blueboy rather than to the more literary Christopher Street. The latter accepted ads for Merrick’s novels but did not review them.

Or is what bothered the critics the fact that Merrick’s characters seemed to have nothing to do with gay politics? Merrick, you could argue, had solved the problem of being homosexual in the U.S. by leaving the country. In France, he claimed, nobody made a fuss about whom you slept with (if you were a foreigner, perhaps; but if you were French, I suspect it was another matter, as is clear in the recent books by Édouard Louis). In Merrick’s own country, homosexuals were often lumped together with Communists.

In his astute chapter on the “gay canon”—the surveys of gay literature—Ortiz points out that Merrick was criticized for not dealing with Stonewall and AIDS. Merrick, whose novels were quite autobiographical, wrote as if Stonewall and AIDS had never happened. But they hadn’t, to Merrick, because he was living abroad. Back in the U.S. for a book tour, Merrick criticized Larry Kramer in an interview for comparing the plague to the Holocaust. (Kramer, when Ortiz tried to get him to talk about Merrick, told Ortiz he had no interest in Gordon Merrick’s novels.) Merrick’s version of gay liberation was living with his lover in Hydra and in Sri Lanka. When asked by Bernard Geis to come out for the publicity campaign for his novel, Merrick declined. “The only thing I won’t accept is an invasion of privacy,” he told Geis. “The book doesn’t prove anything about me, any more than Crime and Punishment proves that Dostoevsky murdered old ladies.”

The irony in all this—the eternal rivalry between art and best-sellers, between gay literature and what Isherwood called “fagtrash”—is that the trilogy begun by The Lord Won’t Mind is basically the story of two men, Charley and Peter, who maintain a relationship over a long span of time. They deal with classic gay issues: shame, internalized homophobia, the moral disapproval of family and society, and the temptation to hide in the closet. And Merrick, true to Maurice, gives his men a happy ending. It ends with the children they’ve fathered coming down the stairs in all their glory. In other words, it ends with something very like the current state of gay liberation: marriage and children. However, in Merrick’s case, it wasn’t a house in the suburbs of St. Louis; it was a place close to a beach on the Indian Ocean.

Merrick chose to live outside the country that he “hated” (he told a French interviewer), no doubt because he didn’t see why he should wait for his fellow Americans to catch up with his own view of things. This view was a curious amalgam of the confidence of an entitled American—his lover Charles Hulse’s younger brother, after visiting the pair in Hydra, thought Merrick a “pompous prick”—and the fear that his homosexuality would make him vulnerable to a society “where he would be doomed to hostility or derision or the half-world of exclusive homosexuality,” in the words of one of his characters. In other words, he was not attracted to the gay ghetto; he simply wanted to love men.

Even the first pages of The Lord Won’t Mind betray this curious mixture of a desire to be free with an earlier, more conventional, even snobbish age, this odd blending of Edwardian manners and modern sexual frankness. You find it in the opening pages of The Lord Won’t Mind, where a man’s “penis” is referred to as his “sex”—as in: “He crouched down, and Peter’s sex leaped and quivered before him, the head as taut and smooth as ripe fruit.” After both men have had an orgasm and Charley is getting up to wash himself, he notices what Merrick refers to as “blood and other matter” on his skin. “Other matter” presumably means feces. That’s why, whatever else people want to call Merrick’s work, they can’t call it pornography, because we all know that in pornography there’s never any shit.

Andrew Holleran is the author of the new novel The Kingdom of Sand (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).