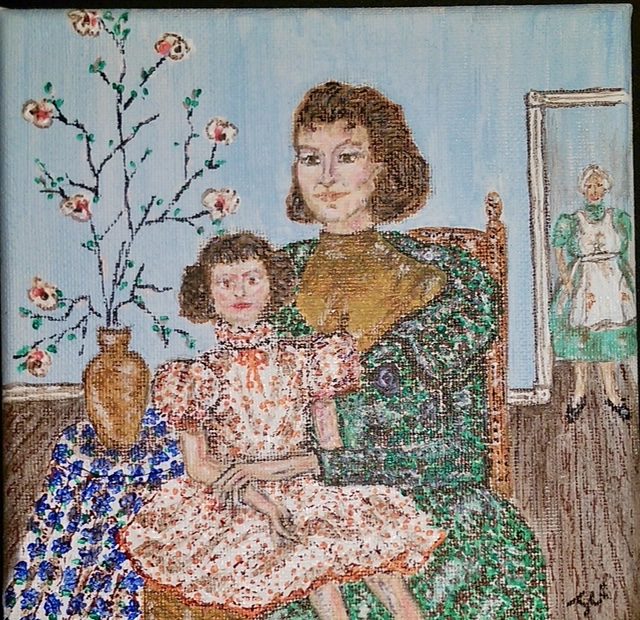

Gay men are obsessed with their mothers. We discuss, analyze, criticize, love, and sometimes despise them. Wild or demure, my mother inspired, guided, abused, and adored me.

Life with Shirley T., was a rollercoaster ride through an Edgar Allen Poe version of Alice in Wonderland. Her peaceable downtimes I relished. Her flipping nightmares I bore with monkish silence. Her madcap express I boarded eagerly. Unpredictable, she was a force to reckon with.

Instinctually, when Mama twisted into a typhoon of terror, I and my five siblings leapt out windows, zipped through swinging screen doors, and beat feet to a safe zone. Demonstratively challenged, Mama stitched our family quilt with barbed wire. We were survivors, weaned on pins and needles.

A seasoned disciplinarian, Mama spanked me once. I was four. Her hair a basket of snakes, she summoned me into the kitchen, her very own culinary court room.

She warned me to never play “Ball & Jacks” on the marble-topped coffee table that displayed her favorite cut-glass basket of flowers. Within seconds, the red rubber ball bounced against the sacred object. The deafening sound of smashing glass echoed through the house.

Mama stood in the archway, in her pinny, neatly tied cotton dress, her hands planted on her hips. “Mr. March!” (A nickname referring to my stubbornness akin to Jo March’s in Little Women).

I squeezed the rubber ball in my pocket. Her eyes, pin wheels of spitting sparks, and her snout, now an inch from my nose, Mama shouted, “YOU! BROKE! MY! VASE!”

Terrified, I smacked her in the forehead with the rubber ball. She stumbled backwards and I bolted. Dashing through a field of wild chicory, I shot into the woods, taking refuge in my secret grotto overlooking the Shenandoah River.

Escorted out of the moonlit forest that evening, my sorrowful siblings surrendered me, kid number five of six, to the executioner. Her lips a slash of coral, she bent me over her knee. I stared at the stained white tiles and wondered whose head would roll.

Rubbing my blistered bum afterwards, I held her gaze. “Don’t. Do. That. Again.”

A Looney Tune character, her eyeballs, lips, and nose dangled on springs, shooting across the room.

Miraculously, no future wallops did I suffer. Though I was spared from the lash, guilt plagued me. Whenever she yanked my brother out of bed, cornered a sibling, or backhanded my sister for necking with her boyfriend, I wanted to die. Mama’s volcanic eruptions were sudden, unpredictable bursts of horror.

A certain Sunday’s eruption haunts me still. The source of all her problems, Dad, froze when Mama plunged a paring knife into his thigh, instantly making me a man at six years old. A coven of cockroaches, my siblings scurried out the nearest exits. I couldn’t move. I was sick of hiding and tired of running, ready to face the music, whatever tune it was she danced to.

I handed Dad a tea towel, which he tied into a tourniquet as I scoured the floor. Mesmerized by the ruby thread circling the drain of the porcelain sink, I scrubbed the weapon to a sparkle, and for a fleeting moment, considered running to the sheriff’s house nearby. Later, I buried the knife in the doll graveyard. Whenever Dad laid out the cutlery for sharpening, I broke into a cold sweat.

As I gaze at the past through my fogged crystal ball, my heart aches for Mama. Undiagnosed, she was manic-depressive, suffering postpartum depression after delivering six children in ten years, and a bulimic to boot. She was her own worst enemy.

The day before he passed away, Dad confessed, “I never could commit her. The embarrassment would have killed her.” Really? She nearly killed us.

Countless times, her grip tight on the steering wheel and her foot solid lead, she sped down the highway in our Ford Country Squire, crammed with kids, a plethora of toys, our dog, Duchess. Spurting gravel, she’d screech to a stop, jump out and barrel across a field, her spike heels clawing the earth.

We sat quietly, reading, drawing, or playing Old Maid.

Her bosom heaving, she’d return about twenty minutes later, smooth the wild hairs spiking her French twist and steer the car into traffic. Isn’t that love?

According to her mother, Grandma Florence, Mama “loved too intensely.”

During a West Virginia blizzard in 1928, she lost her darling baby brother, whom I resembled. Weakened by pneumonia, and with the only doctor snowbound on the other side of the mountain, Mama resolved to save him with the power of love. After stringing popcorn on the Christmas tree for his delight, she hugged him close in her warm bed, but awoke in the wee hours, clutching a cold corpse.

Understandably, Mama detested Jesus’s birthday. My seventh Christmas was the worst. Enraged over God knows what, she dragged our decorated tree, its ornaments tinkling ice cubes in a Manhattan, across the living room, and with a heave-ho, she tossed the shocked spruce into a snowbank.

After that, I withdrew; made myself as small as possible. Uncertain about who might greet me at the bus stop, Mama Jekyll or Mama Hyde, I never invited friends to our house.

I cherished the blissful days when her mood leveled out or she’d pop Valium like ticktacks. Her creativity unleashed; she’d tap lightly on the kitchen table as she kneaded the dough for our daily bread. “Play your piano pretty Mr. March.” Fantasy was Mama’s forte when her fertile imagination breathed freely.

In the tightly laced morals of the 1950’s-60’s, most viewed Mama’s sense of humor as odd. The sight of comedians such as Red Skelton or Milton Berle donning drag on their TV variety hours could snap her out of despair faster than electroshock therapy. Inspired by their antics, she’d paint my face and zip me into a treasure from her wardrobe. Her full skirted, green taffeta cocktail dress was my favorite. Holding the dress in front of her to demonstrate the quality of the fabric, she pinched an inch of the hem between her fingers and twirled around the room. “See Mr. March. Good fabric has swing!”

To waste a sunny day was a sin against nature in her book. A kite’s tail waving merrily from the heavens, she, with me clutching her apron strings, would trot across a blue bell infested pitch, racing the wind.

Once the sunlight sawed through the storm clouds in Mama’s world, she transformed into the mother I’d wished for. Dropping the dour dread of depression, she’d surprise me with picnics in the snow, nature walks on Afton Mountain, and shopping trips.

Perfectly coifed, her makeup flawless, and her dress exquisitely tailored, off we’d fly, Shirley T., and me. Post-shopping lunch at my favorite Woolworth counter was a special treat. Perusing Life Magazine, she’d sip her black coffee as I scarfed down a banana split, basking in the age of Aquarius…until it vanished like Brigadoon.

Detesting pretense and duplicity, she, at her regal best, stood strong against prejudice. When my father asked her if she thought one of my siblings might be gay, she didn’t hesitate. “Yes. Yes, I do,” she stated nonjudgmentally. Growing up, she and my grandmother referred to gay men as “fine young men.”

Fearful, but determined to come out to her, and having passed up a million opportunities to do so, I stood in her kitchen one Saturday morning in 1978, blabbering about why I’d spent so much time with a certain chap. Calmly, she wiped her hands on her pinny and said, “because you’re gay Mr. March.”

At my brother’s wedding, she defied protocol and insisted that my ex-partner escort her down the aisle, where he sat with our family. That’s who she was. A misunderstood underdog herself, she defended the outcast and the downtrodden. “Dignity is everything,” she said.

In the still hours of her last day, she summoned us to her death bed and apologized for the worst of times we’d suffered under her rule. “I love you,” she whispered. Shirley T.’s final smile, lovely and serene, captured a bewildering innocence foreign to our seasons of shadows together. I wept.