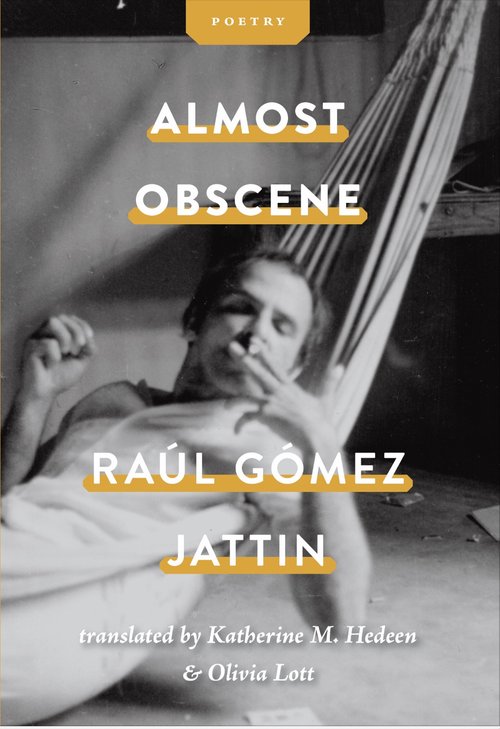

ALMOST OBSCENE

ALMOST OBSCENE

by Raúl Gómez Jattin

Translated by Katherine M. Hedeen and Olivia Lott

Cleveland State Univ. Poetry Center. 132 pages, $18.

I HAD NOT HEARD OF Raúl Gómez Jattin (1945–1997) before the publication of Almost Obscene, a marvelous collection of his poems newly translated from the Spanish. My ignorance may be excused by the fact that this is the first English translation of this remarkable Colombian poet. As the translators point out, even in a 600-page volume on the history of Colombian poetry, he is reduced to a footnote. And yet, he is “the country’s most controversial literary figure.” How does one reconcile his controversial significance with this official neglect?

I’m afraid it’s an old story. Gómez Jattin was gay, and his sexual identity played an important part in his poetry. Not only was Gómez Jattin gay, but he also suffered from schizophrenic episodes. For much of his life he lived on the street, in jail, and in mental hospitals. But no matter where he was living; the important thing is that he kept writing.

Gómez Jattin was not an outsider artist, untutored in the literary tradition. While attending law school, he became involved in the Bolivian experimental theater, producing adaptations of Aristophanes, Swift, and Kafka, along with various Latin American authors. Almost Obscene contains poems referring to Mary Renault, Stendhal, and Constantine Cavafy, plus a string of poems on mythological and historical figures, including Theseus, Medea, Antinous, and Scheherazade.

But most of the poems are erotic. Take “Priapus in the Hammock”: “Now you’re right here in the closeness of my hammock/ stretched out like a sleepy priapic faun/ the body of your masculinity surrendered/ I don’t love you so much but I need you more than this poem.” I’m taken by the phrase “Masculinity surrendered,” which implies that masculinity is under siege. As we will see, dark forces are at work to destroy his masculinity. Yet, in the hammock, that symbol of ease and pleasure, the beloved is able to surrender himself peacefully, lovingly, willingly. It is significant that the cover of Almost Obscene shows the half-naked body of Gómez Jattin in a hammock, puffing on a cigarette with obvious satisfaction. But why does he need “the beloved” more than he needs the poem? People are more important than poetry. Perhaps. But Gómez Jattin sees love as equal to poetry. One answer is that poetry requires a surrender to language that only love can teach.

It’s important to bear in mind that Gómez Jattin’s work kept changing over time. Unlike that of so many mad poets, it didn’t freeze. The priapic poems—to use his word—faded, and he entered a more embattled world, a “psychomachia.” In its simplest form, the psychomachia is a mental battle between good and evil. Recall the cartoons in which a red devil, pitchfork in hand, stands on Elmer Fudd’s left shoulder, urging him to “kill the rabbit,” while a haloed angel on his right coos “love your enemies.” That’s the floorplan of a psychomachia. Yet in Jattin’s case, it’s hard to say which spirit is demonic and which is angelic. In one poem, the white spirit encourages him to sing at the top of his voice in the hopes that it will kill his mother. It doesn’t succeed. In another poem, in which he sees a police car drive by, he understandably “slams the door in pure panic.” Then the maid appears with “a tail tipped with a poison dart” and the white wizards whisper: “Don’t eat anything. It’s all been poisoned/ Don’t lie down don’t doze off/ … If you fall asleep the devil will take you away.” Hardly sound advice.

Yet these poems are often comic and sometimes joyous, with a certain Charlie Chaplin pathos. Gómez Jattin writes of lying on a sidewalk watching the stars and hoping to sleep on a park bench. “He drags himself back toward the park. And finds it empty. Such happiness!” and then “dreams of paradise.” In yet another poem, he tells himself: “Let’s get ready to die bravely.” But in the end “death doesn’t show up.”

He is divided as well by masculinity and femininity, and many of these poems describe both the rupture of these identities and his attempts to reconcile them: “I’m about a woman and a man Broken/ by a tender virility,” he writes in two lines full of paradox. The man and woman joined spatially are separated by the gap in the line before the word “Broken,” which is capitalized to indicate a new sentence. Ironically, what breaks Gómez Jattin is a “tender virility.”

In his last days, Jattin visited his psychiatrist, to whom he gave a seahorse, because seahorses are hermaphrodites. Then he drank all night, and the next morning he was run over by a bus. An accident or suicide? There isn’t always that much of a distinction.

The translations by Katherine M. Hedeen and Olivia Lott are wonderfully straightforward, clear, and frightening. I long to see translations of all his work. ____________________________________________________

David Bergman is a professor of English at Towson University, MD.