J. C. LEYENDECKER (1874–1951) was an artist of many firsts. With his illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post, he can be said to have invented what the modern magazine cover should look like. He was one of the first popular artists to achieve a kind of greatness, and, as the most widely seen image-maker of his era, he defined the look of the fashionable American male during the first few decades of the 20th century. As a gay man himself, he did all this while introducing a subtly homoerotic subtext into many of his drawings, thereby prying open a crack in the closet door of his era.

In spite of his extraordinary achievements, his name nearly vanished after he died in 1951. Seven decades later, an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society titled Under Cover: J. C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity [reviewed here in the May-June 2023 issue]turned a spotlight on his work when it opened last May, providing a forum for conflicting viewpoints about Leyendecker’s art and life.

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was born in Montabaur, Germany, in 1874, and emigrated to Chicago with his family when he was eight years old. He showed a precocious talent for drawing, studying at the famous Art Institute of Chicago when he was only fifteen. Such was his ability that his teachers encouraged him to study in Paris, which was the mecca for serious artists at this time. As luck would have it, his brother Frank (1876–1924) was also a talented artist—nearly as good but not as disciplined as Joseph. Together they traveled to Paris in 1896, where they enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, which was headed by the influential William-Adolphe Bouguereau. At this point in their lives, the two brothers were as thick as thieves, but their lives were destined to diverge.

The classical training that Joseph received in Paris strongly shaped his approach to art. His teachers, who looked down on “commercial” artists, made him copy the Old Masters. However, as soon as he hit the Paris boulevards, he found himself surrounded by the publicity posters of artists like Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha, whom he admired and befriended. These artists believed in a revolutionary idea that challenged the art establishment: Great art could be produced for visionary companies that manufacture products for the masses. Inspired by this manifesto, Leyendecker won a contest for the cover of the magazine The Century with an image clearly influenced by Mucha. The cover was so popular that it was sold as a poster, something unheard of at the time. The realization that he could make money and get famous by creating art for the masses, not just for wealthy patrons, stirred his imagination. This trend had yet to reach the U.S., and he saw an opportunity back home, so he and his brother Frank returned to Chicago and opened a studio.

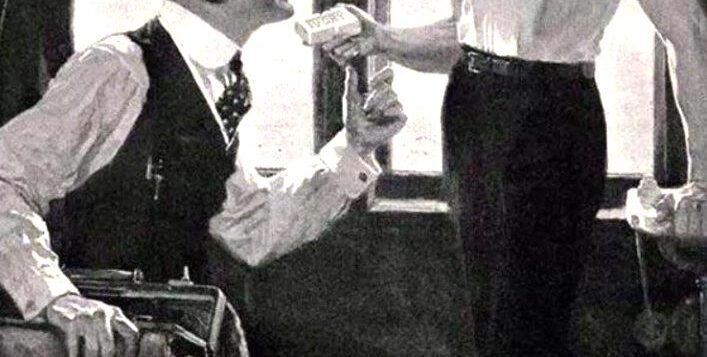

J. C. Leyendecker became a full-time illustrator, creating images for advertising that fulfilled the radical ideal that he’d learned in Paris: “My illustrations introduce art into the details of everyday life, refining and improving them,” he declared. It wasn’t long before he created his first cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, in 1899. His innovative contract allowed the Post only a one-time use of a given illustration, with rights returning to the artist after publication. It was an arrangement that he insisted upon for his whole career.

Ignacio Darnaude is an art scholar, lecturer, and film producer. He is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Queer Code in Art.

Discussion1 Comment

There’s an amazing trove of Leyendecker’s work in Stockton, California (of all places), at the Haggin Museum, which also has a great collection of art and historical artifacts. And the museum texts are quite open about his sexuality. Worth a day-trip from the San Francisco Bay Area. Web site is hagginmuseum.org.