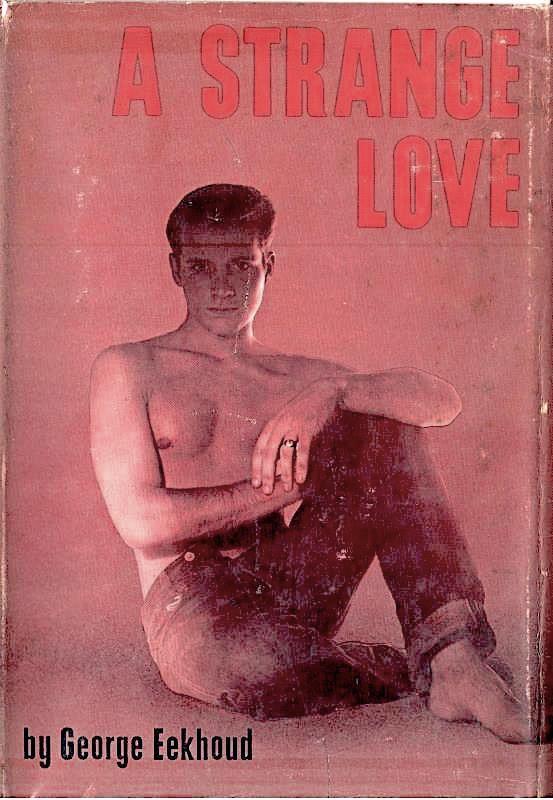

IN 1965, Guild Press published Georges Eekhoud’s queer novel Escal-Vigor under the title A Strange Love, with a picture of a handsome, bare-chested young man on the front cover (Figure 1). The back cover doesn’t reveal any details about the author, and the front flap includes scant biographical details: “Georges Eekhoud is one of the leading writers of this century, and this beautifully written book was one of the pioneering works of fiction dealing with the subject matter of homoeroticism.” The back flap lists his publications, with French titles, but no dates (this list is reproduced inside the book too).

The title page reveals that A Strange Love has a subtitle, Escal-Vigor, followed by “From the French of George Eekhoud.” However, nothing indicates that this novel was first published in 1899, and anyone picking up the book would be led to believe that it was by a contemporary writer. The introduction takes a somewhat militant stance—Eekhoud is described as “one of the best-known classical writers of modern Belgium”—but does not provide any context. A Strange Love is compared to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Eekhoud’s acquittal on “Friday the 26th of October, 1900” is mentioned. Readers would no doubt have been disappointed to discover that the most erotic scenes in the book involve two passionate kisses.

An English translation of Escal-Vigor was published in 1909 by Charles Carrington. Panurge Press reprinted this translation in 1930 and Guild Press in 1965. There are no significant differences between these translations except for the illustration by Carroll Snell in the 1930 edition, which depicts a woman in the foreground who’s baring her bosom and showing one nipple. The drawing also shows a furious and violent crowd throwing stones and, in the background to the right, a well-dressed man hovering over a shirtless man. This illustration is a dramatized and eroticized version of the final scene of the book (Figure 2).

Eekhoud was born in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1854. He died in Brussels in 1927 after a long career as a prestigious novelist and journalist, as well as a critic of art and literature. He’s mainly remembered today as a queer pioneer: Escal-Vigor is considered the first novel in Belgium to depict love between two men, and his queer short stories are still published in French editions and were translated into Spanish as recently as this year.

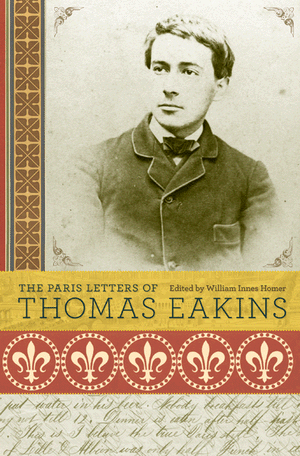

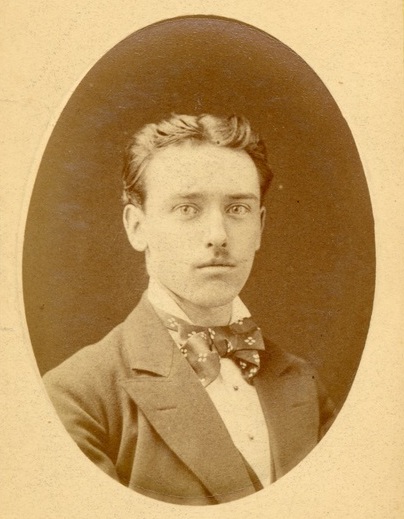

Eekhoud was orphaned at a young age and taken in by his wealthy maternal uncle, an industrialist. He enjoyed a privileged upbringing at the exclusive Swiss boarding school Breidenstein Institute, where he received an excellent education and learned several languages. It was here that he first understood his queer desires. In notes he prepared later in life, he revealed his special friendship with Giuseppe Facchini, a “handsome and strong” sixteen-year-old from Bologna. His friend “was more than a brother” to him and took care of him “better than any mother” when he injured his ankle and was bedridden. Eekhoud also recalls that Giuseppe gave him all of his chocolates and a book by Victor Hugo. He was also fascinated by another schoolmate: “Boratto was well built, handsome like Saint Sebastian, with frizzy hair, a matte and slightly olive complexion, big lips and large eyes.” Eekhoud recalls that this friend used to strip his shirt off to show his muscles and would perform gymnastics for his friends; he admits openly that he felt “passion” for him. Boratto would “gently tease him and squeeze his cheeks” while fixing his “velvety eyes in mine.” These infatuations would inspire his writings on queer love (Figure 3).

At age eighteen, Eekhoud was unsure of his future path, and first decided on a military career. He was admitted to the prestigious Royal Military School in December 1872, only to be summarily dismissed in June 1873. The official reason was an unsanctioned duel with his friend Camille Coquilhat. However, the exact circumstances remain murky and the relevant page in the official record has been ripped out. Eekhoud started working as a corrector for a local newspaper in Antwerp, to which he also contributed articles on various topics. With his grandmother’s financial assistance, he published three volumes of poetry between 1877 and 1879, which passed wholly unnoticed in literary circles. During these formative years, he met the young generation of Belgian writers and established ties that would serve him well in the future.

In 1881, Eekhoud moved to Brussels and started working as a journalist for the important daily newspaper, L’Étoile. He also contributed regularly to Belgian avant-garde literary journals. His first volume of short stories, Kermesses (“Country Fairs”), was published in 1884, to critical acclaim. The author’s queer desires appear in the suggestively erotic tone used by the narrator to describe male characters in some of these stories. For example, one character is an “eighteen-year-old brunette, slender, a little pale, shy and girlish,” while others are depicted as “solid square and muscled guys, with brown fuzzy hair.” In one story, a female character observes a soldier getting undressed, as the narrator describes the scene: he has “a head of frizzy chestnut hair shaped like a helmet … a slightly aquiline nose … a square chin and broad shoulders.” The reader becomes a complicit Peeping Tom when the soldier “unbuttons his tunic, takes off his belt; and shows his pectoral muscles in their full glory.”

In 1887, in an effort to keep up bourgeois appearances, Eekhoud married his grandmother’s former housekeeper, Cornélie Van Camp (1847–1920), and a year later they adopted his wife’s orphaned niece and nephew. In the meantime, same-sex attraction had become a more visible theme in his fiction. Nouvelles Kermesses [“New Country Fairs”], his second volume of short stories, was published in 1887. “Fit for Service” is the story of Frans Goor, a poor villager who’s selected for the army draft. The narrator describes the young man’s perfect naked body during the physical examination by the medical board. The doctors admire Goor’s pectoral muscles, probe his “intimate parts,” and declare him fit for duty. Garrisoned in Brussels, Frans is witness to strange activities at night in the dormitories: he sees other soldiers’ in “strange postures” and hears “moans of love, the suppressed sighs, the empty kisses.” These same soldiers try to seduce him, but to no avail; Frans is in love with a girl from his village. This refusal to indulge in queer sexuality leads to his downfall. When Frans refuses his sergeant’s advances, the latter accuses him of theft and threatens to strip-search him. Frans throws a jug at the sergeant’s head, wounds him, and is then sentenced to five years in the brig. Ashamed of his behavior, he takes his own life.

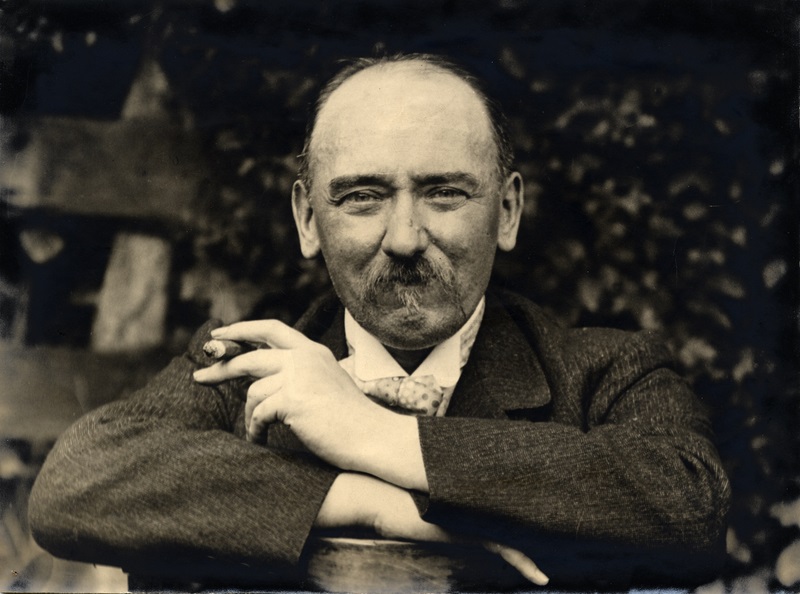

The following years brought success after success for Eekhoud: he published La Nouvelle Carthage (1888, 1893)—translated into English as The New Carthage (1917)—which was widely praised as a masterpiece. In 1893, he was awarded Belgium’s most prestigious literary award for this novel. We know very little about Eekhoud’s extramarital love life before 1892, but on February 22nd of that year, he met Sander Pierron, a twenty-year-old typographer’s assistant. The 270 letters sent by Eekhoud to Sander between 1892 and 1927 allow us to follow the evolution of their friendship. Eekhoud uses common pleasantries in his first letters to Sander, calling him “dear friend” or “dear Sander.” A few months later, the tone changes when he writes “dear little Sander” or “my darling,” and in February 1894, “My darling, my beloved.” Eekhoud uses English to express his love, no doubt so that his wife would not understand (Figure 4). (Here and following: italics are used for passages that Eekhoud wrote in English.)

The correspondence is filled with statements of undying love: “I have a never-ending affection for you, a love that will only end with my life … Tell yourself that I’m all yours; that everything I can do for you will be done, that no one, you hear, loves you like I do” (April 12, 1893). Other excerpts clearly indicate that this is not platonic love: “my beloved little Sander … Yes, my dearest, I too love you more than anyone else in the world, and every day I find myself feeling more and more attached to you. … I kiss you with all my heart … thousand kisses; our souls are full of love; Thousand kisses my loving and most beloved Sander … thine for ever, thy only, Georges; My heart full of joy and of love, all spread and smelted in thee, my only love” (September 1893 to May 1894).

Although Eekhoud’s diary was heavily censored and even partially destroyed—by himself or his inheritors—fragments survive that also testify to the sexual nature of this relationship: “Excellent evening of excitement with Sander” (January 28, 1895); “Last night he was exquisite, caressing, as affectionate as I’ve rarely seen him. And I began to hope again, to rejoice, to saturate myself with his ineffable and delicious presence” (March 30, 1895).

Sander was engaged in January 1895 and married in August 1896, but the two men still saw each other and continued their romance. Eekhoud writes to him on January 28, 1897: “I was thirsty of thy lips and of thy heart,” and on April 10, 1897: “my heart was thirsty of thy sweet presence and my lips did long for thy at the same time mighty and caressing kisses.” In a letter three days later, he sends Sander his “most raving and hot kisses.” The letters from the latter part of 1899 show that their sexual relationship had ended by then. However, they remained the closest of friends until Eekhoud’s death.

In parallel to his newfound love, Eekhoud published more militant queer texts in collections of short stories such as Le Cycle patibulaire (“The Sinister Cycle”) (1892, 1896) and Mes Communions (“My Communions”) (1895, 1897). His anarchistic ideology is a central thread: if “normal” society refuses to accept his desire to love men, then one should seek such love on the margins of that society. Although many of his heroes meet their death in his prose, these outcomes, in our view, do not necessarily constitute a condemnation of queer love. Rather, Eekhoud uses the characters’ martyrdom to denounce society’s intolerance.

For example, “The Lancer’s Quadrille” starts with the ceremonial dismissal of a “very young and handsome cavalryman” from the army for “indecent assault.” The lancer sees his dismissal as a sign of society’s intolerance of queer love and decides to avenge this injustice. He goes to a popular dance hall, where he’s recognized and forced to submit to a test: the female dancers each have one dance during which to seduce him, but they all fail, and then threaten to gang-rape him. The lancer next reminds the male dancers of their own adolescent same-sex experiences, which causes them to be disgusted by their girlfriends who, in a fit of jealous rage, put the lancer to death. The implied message here is that everyone can be queer, and people should follow their desires instead of submitting to moral strictures. One also wonders if Eekhoud was recalling his own dismissal from the Royal Military School in 1873, since he published this novella after his friend Camille Coquilhat’s death in 1891.

“Appol and Brouscard” tells the story of two young men who meet in prison, fall in love, and join a criminal gang in the Brussels underworld, where their relationship is accepted. Brouscard’s description seems inspired by Eekhoud’s aforementioned school friend Boratto. Appol, a former prostitute in the Port of Antwerp who has “a rosy complexion, a delicate face, silky and fine blond hair, sapphire-like blue eyes,” and is “beardless with a nascent moustache.” His description is suggestive of Sander Pierron.

“A Bad Encounter” and “The Sublime Escarpment” are two stories that narrate love between men from different social classes. In the first, the wealthy thirty-year-old prince Léonce de Mauxgavres falls in love with Daniel Thévenot, a handsome adolescent, at a popular dance hall. The novella contains a surprising scene: two men dance intimately. Everyone is “stupefied,” but it’s unclear whether they’re shocked because two men dance together or because Léonce managed to find a partner so quickly. “The Sublime Escarpment” takes place in Turin, Italy, and is the fictional portrayal of the relationship between the rich and famous Turin lawyer Teodato Zambelli and Papurello Rellino, a young criminal from a popular neighborhood, who sacrifices his life to save his beloved’s reputation.

When Oscar Wilde was condemned to two years of hard labor in May of 1895, Eekhoud protested by publishing Court in the Boiler Room in a Belgian literary journal in September of that year. The novella is dedicated to “M. Oscar Wilde, the Pagan Poet and Martyr, tortured in the name of Protestant Justice and Virtue.” At its center is the field trial of an unnamed aristocrat imprisoned for his queerness. He defends himself by declaring he is the “cursed lover, born under the sign of Urania” and continues with an impassioned plea in defense of queer love: “Crime against nature, they would say! Against what nature? Hasn’t my whole life been a crime against my own nature?” The other prisoners accept him as he is and declare his love to be pure. At its publication, this brazen defense of Wilde was discussed in the Belgian and French press and widely praised.

Escal-Vigor was first published in 1898 in the Parisian literary journal, Mercure de France, and in book form the following year. The novel follows the queer Count Henry de Kehlmark, who returns to the ancestral castle of Escal-Vigor on the conservative island of Smaragdis, where he falls in love with eighteen-year-old shepherd Guidon Govaertz. The sexual nature of their relationship is alluded to discretely, but Kehlmark makes impassioned statements in defense of queer love. On one occasion, he declares that Guidon is the “first and the only one to satisfy the first need of my being. If our flesh has done aught ill, the most complete moral fervor was our accomplice. Our feelings coincided with our desires.” When urged by his housekeeper to change his nature to avoid the wrath of the local populace, Kehlmark states that he wants to “remain myself, [and]not to change! To remain faithful unto the end to my true and legitimate nature! Had I to live again it is thus that I would love, even were I to suffer as much, or even more, than I have suffered.” In the final scene of the book, Guidon and Henry are put to death by a furious mob as they exchange one last passionate kiss.

Notwithstanding Eekhoud’s careful depiction of queer love in this novel, he was accused of breaking the law related to the distribution of pornography and put on trial in October 1900. Hundreds of French and Belgian intellectuals signed a petition in his defense, including some of the best-known writers at the time: Émile Zola, André Gide, and Jean Lorrain. His acquittal was a moment of triumph in the press, and Escal-Vigor became Eekhoud’s biggest commercial success, with six print runs between 1899 and 1901 (a total of twelve by 1930). The novel was translated into German (1903), English (1909), and Russian (1912) (Figure 5).

In 1904, Eekhoud published L’Autre vue (“The Other View”), reprinted in 1926 under a more provocative title: Voyous de velours (“Velvet Rascals”). In this novel, the main character, Laurent Paridael, professes his love for young working-class boys from the slums of Brussels who wear velvet trousers. The surviving parts of Eekhoud’s diary for 1902 show that the author shares this fetish for the velvet pants worn at the time by working-class men. “I had him yesterday. It was long since I had got him in his velvet [breeches]. We had a [splendid]sixty-nine” (March 27, 1902). “Friday last I had my velvetian. He had on his velvet breeches; we had a splendid sixty nine and enjoyed each other simultaneously” (June 23, 1902). “Yesterday we enjoyed each other almost at the same time. I did throw him in intense raptures of delight. How we kissed and licked each other” (September 13, 1902). “This evening we enjoyed each other thoroughly and did lay half an hour and almost naked in my room upstairs. He was delicious” (October 16, 1902). “Yesterday he was delicious, his [illegible]stood splendidly and we had our raptures almost at the same minute” (June 12, 1904).

Eekhoud’s reputation as a defender of same-sex love was firmly established after his acquittal in 1900 and he created a network of European queer intellectuals that included Oscar Wilde, Magnus Hirschfeld, André Gide, Edward Carpenter, Rachilde, Jacob Israël de Haan, Eugen Wilhelm, Karl von Levetzow, Elisàr von Kupffer, and others. Together, they discussed queer love in their works and helped each another to find editors and journals in which to publish. When Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen created Akademos in 1909—the first Francophone journal with an explicit primary focus on queer love—he solicited Eekhoud’s help to find contributors. In 1920, Eekhoud was nominated by King Albert I as one of the fourteen founding members of the Royal Academy of French Language and Literature of Belgium. In 1927, he was elevated to the rank of Commander in the Order of the Crown, one of Belgium’s highest honors. It seems that officialdom had forgiven him for being a defender of “abnormal” love. When he died on May 29th of that year, his funeral procession was led by none other than his faithful friend Sander Pierron (Figure 6).

Michael Rosenfeld, a postdoctoral fellow in queer literary history at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium), is co-editor of The Italian Invert: A Gay Man’s Intimate Confessions to Émile Zola (2022).