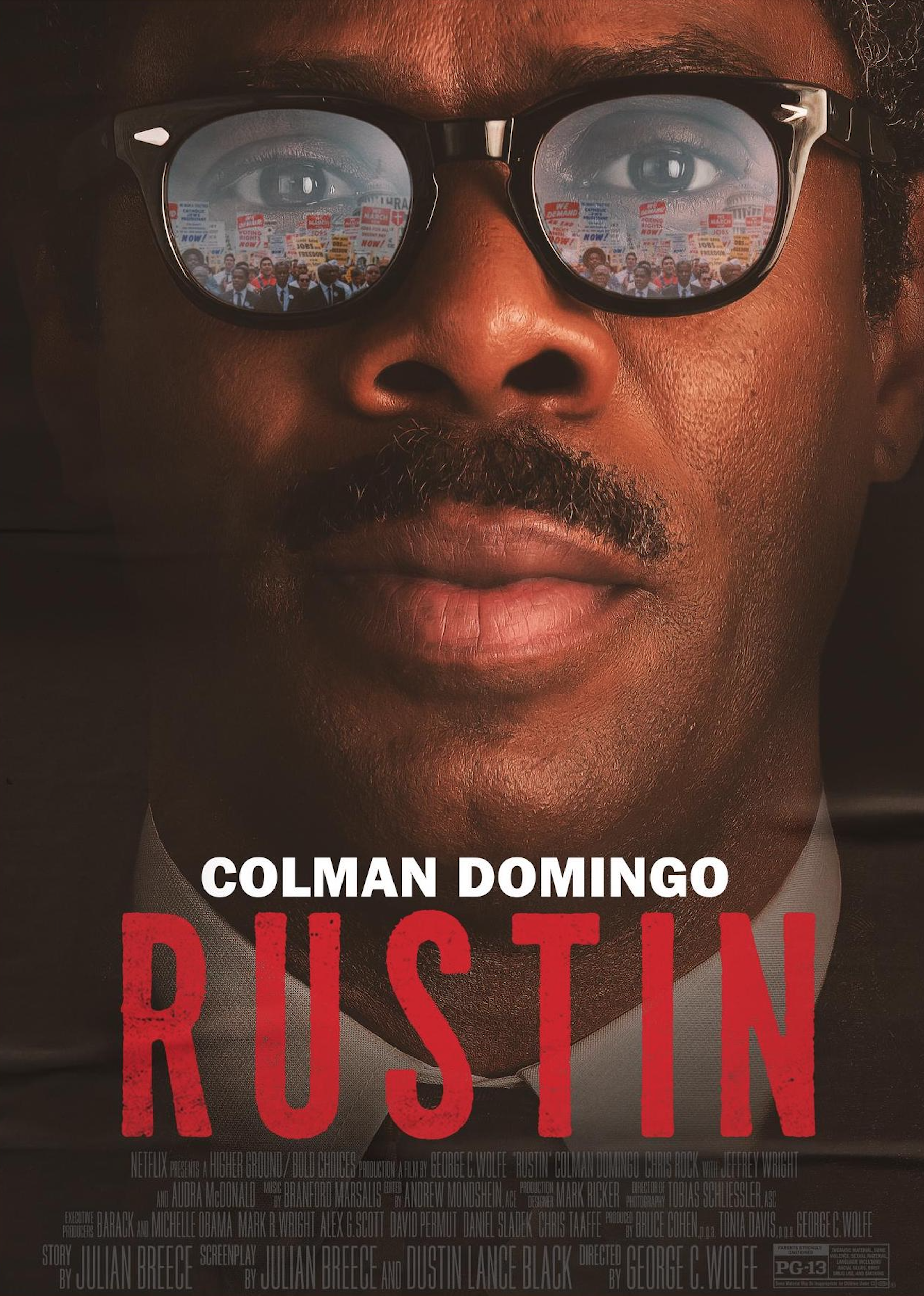

RUSTIN

RUSTIN

Directed by George C. Wolfe

Higher Ground / Netflix

ONE COULD reasonably make the argument that Bayard Rustin had a greater impact on the history of the 20th century than any other gay American man. He deserves more credit than anyone for bringing Gandhian peaceful, nonviolent resistance into the heart of the African-American freedom struggle. He successfully strategized how to make a minister in Montgomery, Alabama—the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.—a leader with a national profile. He organized and participated in actions on four continents to protest the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons—campaigns that helped bring about an international agreement to ban such testing. Most notably, perhaps, he was the key organizer for what became the most iconic demonstration in U.S. history: the 1963 March on Washington.

Despite these achievements, Bayard Rustin is a name that few people will recognize, and the reason is clear. He was a gay man in a period of U.S. history—the 1940s through the 1960s—when the oppression of LGBT people was at its worst. Arrested more than once for his sexuality, Rustin learned to do his activist work in the background, to avoid being seen as “the leader” even when he was central to an event. In addition, his sexual identity led other key activists in both the peace and the Civil Rights movements to attack him repeatedly and to force his removal from organizations and from protest campaigns.

Much to my satisfaction, the new film Rustin, directed by George C. Wolfe and produced by the Obamas’ foundation, does an excellent job of confronting directly the homophobia that Rustin faced from other African-American leaders while also capturing his charisma as a political organizer and strategist. Not a biopic encompassing the length of his career, Rustin zeroes in on the event that audiences will be most familiar with, the 1963 March on Washington. It begins in 1960, when Roy Wilkins, the head of the naacp, and the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, a member of Congress representing Harlem, threatened to go public with the blatant lie that Dr. King and Rustin were having a sexual affair. This led Dr. King to break with Rustin, perhaps the most painful moment in Rustin’s activist life. For the next two and a half years, as the Civil Rights movement exploded with sit-ins and freedom rides, Rustin found himself forced to watch from the sidelines.

Having set this context, the film then jumps to 1963, which remains its focus. It lays out the tremendous work that went into organizing, in just eight weeks, a peaceful march of 250,000 people. It reveals a new round of despicable efforts by Wilkins and Powell to have Rustin removed from planning for the march as well as the admirable and unflinching support that A. Philip Randolph, a long-time Black union leader, provided to Rustin. And it shows how, despite these backroom fights, Rustin succeeded in motivating a large team of young activists to work day and night to make it happen.

Besides the film’s commitment to hiding none of the conflict and pain that swirled around Rustin, it does a wonderful job of portraying the complexity of Rustin’s personality. Colman Domingo, who plays Rustin, lets us see the charismatic aspects of Rustin as organizer. Some of the most inspiring scenes consist of Rustin provoking both laughter and determination in the faces of the many young women and men, both Black and white, who spent a summer doing whatever was necessary to organize this historic event. At the same time, Domingo nicely conveys Rustin’s personal struggles to find both sex and romance in an era when virtually all LGBT people were closeted, when many led double lives, and when socializing in settings like gay bars or cruising in public places might lead to an arrest.

Rustin successfully restores to memory a life worth remembering in a style both dramatically compelling and emotionally uplifting. It puts a Black gay man front and center in American history, where he belongs.

John D’Emilio is professor of history at the Univ. of Illinois, Chicago.