WHILE the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion in New York’s Greenwich Village is generally considered the spark that ignited the gay liberation movement in the U.S., San Francisco was the true epicenter of gay life for much of the previous century, as demonstrated by the following chronology of quick takes that briefly highlight some of the pioneering individuals, organizations, publications, and events that took place in San Francisco.

Jack Bee Garland was born in San Francisco in 1869, exactly one century before the Stonewall Riots. Assigned female at birth, he lived as a male—known variously as Elvira Virginia Mugarrieta, Babe Beam, Jack Beam, Jack Maines, Beebe Beam, and Ben Garland—in the city’s Tenderloin District, where he had erotic relationships with young men, an early example of a trans man who was sexually attracted to other men. He enlisted in the U.S. Army, worked as a journalist, nurse, and adventurer, living as a man for nearly forty years before dying at 67 in 1936.

Twenty-eight-year-old Oscar Wilde visited San Francisco on March 27, 1882, sporting lavender pants, seal fur cuffs, an ivory cane, and his biting wit. The San Francisco Chronicle reported: “The city is divided into two camps, those who thought Wilde was an engaging speaker and an original thinker, and those who thought he was the most pretentious fraud ever perpetrated on a groaning public.” Wilde’s bon mot about San Francisco in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) is often quoted: “It’s an odd thing, but everyone who disappears is said to be seen at San Francisco. It must be a delightful city, and possess all the attractions of the next world.”

Marie Equi and Bessie Bell Holcomb left their Oregon homestead in 1897 and moved to San Francisco. Marie pushed through boundaries of class, gender, and sexual orientation on her way to becoming a medical doctor. As the only volunteer female doctor on the Oregon relief mission aiding victims of the 1906 earthquake, Marie was put in charge of an obstetrics unit in a 300-bed hospital. Countless newspapers detailed stories of Marie’s compassion and professionalism, and the U.S. Army awarded her with a medal and citation for her relief work.

American author and editor Charles Warren Stoddard set his 1903 autobiographical novel For the Pleasure of his Company: An Affair of the Misty City, Thrice Told against San Francisco’s bohemian social scene. Best known for his travel writing about Polynesia, Stoddard praised South Sea societies’ receptiveness to homosexual liaisons, and he lived in relationships with men, including with Francis Millet and Yone Noguchi [discussed elsewhere in this issue]. His only novel begins with the words “Here you have my Confessions” and supplies enough information to enable the reader to trace out the whole story of his life.

John Chaffee died in San Francisco on July 31, 1903, and his life partner Jason Chamberlain—having received word by mail—shot himself in the head with a shotgun on October 16, 1903. The two had left Boston together in January 1849 and arrived in San Francisco at the height of the gold rush. Despite the stable jobs and good pay, they left together for Calaveras County to try their luck at gold mining and in 1853 settled in Second Garrote, a small rural settlement in Groveland, Tuolumne County, where Chaffee mined and Chamberlain farmed and maintained an apple orchard. The pair lived there for fifty years and had planned to be buried side by side, but Jason was buried in Groveland and John in Oakland. Bret Harte probably used the couple as models for the characters in his 1869 short story “Tennessee’s Partner.”

The Dash, considered the city’s first gay bar, opened at Pacific Avenue and Kearny Street in 1908. The city may have had gay bars before The Dash, but none as notorious. The bar featured cross-dressing waiters who performed sex acts for a dollar in nearby booths. After a high-profile judge was linked to the bar, it was closed by the vice squad amid much fanfare. The scandal led to a reform movement that helped shut down the infamously sexually liberal Barbary Coast district.

Elsa Gidlow moved to town from New York in 1926, at the invitation of Kenneth Rexroth, known as the father of the San Francisco Renaissance. Gidlow is best known for writing On A Grey Thread (1923), considered the first volume of openly lesbian love poetry published in North America. In 1954, she purchased Druid Heights, a rustic retreat near Mill Valley, which became a spiritual home to a number of influential writers and thinkers. Gidlow’s 1986 autobiography, Elsa, I Come with My Songs: The Autobiography of Elsa Gidlow, offers a detailed account of seeking, finding, and creating a life with other lesbians at a time when very little had been written on the topic. The first lesbian autobiography in which the author did not use a pseudonym, it offered a superb account of one participant-observer’s view of 20th-century artistic and bohemian life and of the cultural history of the Bay Area.

On February 24, 1931, pioneer sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld arrived in San Francisco for a ten-day sojourn, giving public talks, paying social and professional calls, and visiting tourist sights. Called “the Einstein of Sex,” the groundbreaking German physician, sexologist, and author cofounded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, the world’s first homosexual emancipation organization.

The Black Cat Café, a bohemian hangout, opened at 710 Montgomery Street in 1933. The bar was at the center of one of the earliest court cases to establish legal protections for gay people in the U.S, which happened in 1950 when Sol Stoumen fought back against the California Dept. of Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) Commission’s attempts to close his bar. For the first time, the California Supreme Court decided that bars cannot be discriminated against solely for catering to homosexuals. Despite this victory, continued pressure from law enforcement agencies eventually forced the bar’s closure in 1964. (Not to be confused with the Black Cat Tavern in L.A., which was the site of a famous LGBT demonstration in 1967.)

Born in 1933 in a Salvation Army hostel in Oakland, Rod McKuen refused to identify as gay, straight, or bisexual: “I can’t imagine choosing one sex over the other, that’s just too limiting. I can’t even honestly say I have a preference.” Best known as a poet of popular verse, he was also an actor and a singer-songwriter. And he was active in the LGBT rights movement as early as the 1950s, holding a leadership role in the Mattachine Society’s San Francisco chapter. McKuen spoke out against singer Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children“ campaign to repeal an anti-discrimination ordinance in Dade County, and often gave benefit performances to aid LGBT rights organizations and to fund AIDS research.

Native San Franciscan Alice B. Toklas returned to the Bay Area with her life companion Gertrude Stein in April 1935. Visiting East Oakland to see the house where she had lived and discovering that it had been razed, the property built over with little houses, Stein observed that there was “no there there,” a comment that has been endlessly misinterpreted as applying to the city of Oakland in general.

The next year, Jack W. Gartman opened Jack’s Turkish Baths, one of the first men-only bathhouse in the city. Open day and night, it was popular with servicemen during World War II. It was included in the Mattachine Society’s bar guide in the 1950s, and by the 1970s it catered to an older crowd. Mona’s, San Francisco’s first openly lesbian bar, also opened at Broadway and Columbus Avenue in North Beach, billing itself as a place “where girls can be boys” and featuring a female wait staff and entertainers dressed in tuxedos. Geared toward the local gay community as opposed to tourists, Mona’s became one of the most popular lesbian bars in the U.S., paving the way for more lesbian bars to open in the neighborhood, which became a “well-known lesbian enclave.”

Bay area native Robert Duncan, a poet and public intellectual, was another key figure in the San Francisco Renaissance. He acknowledged his own homosexuality in his landmark August 1944 essay “The Homosexual in Society,” one of the first public defenses of homosexuality in the U.S. He often collaborated with his life partner, the renowned visual artist Jess Collins (known simply as “Jess”).

While a student at U.C. Berkeley in January 1949, shortly after her 16th birthday, Susan Sontag met Harriet Sohmers Zwerling, who introduced her to the queer bohemian scene in North Beach and Sausalito. After their brief affair, Sontag wrote in her journal: “my concept of sexuality is so altered—Thank God!—bisexuality as the expression of fullness of an individual. I know now a little of my capacity… the wonderful widening of my world which I owe to Harriet. Everything begins from now—I am reborn.”

Douglass Cross and George Cory, songwriters and lovers, homesick after moving to Brooklyn, wrote “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” in 1954. Their famous pæan to the City by the Bay was popularized by Tony Bennett at a December 1961 concert at the Fairmont Hotel’s Venetian Room, and in 1969 it was adopted by the City and County of San Francisco as one of two official anthems (the other being the title song from the 1936 film San Francisco.) Over twenty years later, the now elderly George Cory underwrote a new show for his friend Hibiscus, a founding member of both the Cockettes and the Angels of Light, titled Femme Fatale: The Shocking Pink Life of Jayne Champagne, which opened at the Montgomery Playhouse.

The first lesbian organization in North America, the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), was founded in San Francisco on October 19, 1955 by four lesbian couples, including Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. The following year, the group began publishing The Ladder, a monthly magazine that ran from 1956 to 1972. The first national lesbian convention, organized by the DOB, took place in San Francisco in May 1960.

The Mattachine Society, the early homophile organization formed in 1950 by Harry Hay in Los Angeles, moved its headquarters to San Francisco in 1956, with Hal Call as president. In 1955, Call cofounded Pan-Graphic Press, which published The Mattachine Review, The Ladder, and other homophile publications. He also founded Dorian Book Service, a gay and lesbian literature clearinghouse. One of the few gay men who spoke publicly about gay issues, Call frequently appeared on local television programs in the 1950s. In 1967, Call founded the Adonis Bookstore, the first gay bookstore in the U.S., in the Tenderloin, just months before New York’s Oscar Wilde Bookstore opened. The Adonis Bookstore, one of the first places to show pornographic gay films, continued until Call’s death in 2000 at the age of 83.

On September 6, 1957, Allen Ginsberg, author of Howl, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, poet and owner of City Lights Bookstore, were unsuccessfully tried on charges of selling obscene literature because of Howl’s descriptions of male homosexuality. Ginsberg had moved to the city in the early 1950s armed with a letter of introduction to Kenneth Rexroth, figurehead of the San Francisco Renaissance, who introduced him to the city’s poetry scene. Also, it was in San Francisco, in 1954, that Ginsberg met his life partner, Peter Orlovsky.

1961 was a banner year: Guy Strait started League for Civil Education (LCE) to organize a gay vote in San Francisco and began publishing the first gay newspaper, distributing LCE News free in bars. Louis Randall Hogan, later famous for The Gay Cookbook, published The Gay Detective using the pseudonym “Lou Rand.” The novel provided a loosely fictionalized guided tour of postwar places and personalities, and was republished in 1965 as Rough Trade. José Sarria, a flamboyant, charismatic, and immensely popular waiter and drag performer at the Black Cat, kicked off his 1961 campaign for San Francisco Supervisor, becoming the first openly gay man to run for public office, and receiving 5,600 votes. “The Rejected,” the first television documentary on homosexuality, was broadcast by KQED on September 11, 1961. Originally titled “The Gay Ones” and later syndicated to NET stations, the sixty-minute program featured legal, medical, and religious experts discussing this “social problem.”

Considered the first gay business association in the U.S., the Tavern Guild was formed in 1962 by proprietors and employees of several gay bars in response to rising tensions between the police and gay people. This coalition helped unify and protect bars and bartenders by fixing drink prices, developing a phone network to track police raids, and setting up funds for members who were unemployed, and also organized fundraisers and charity events.

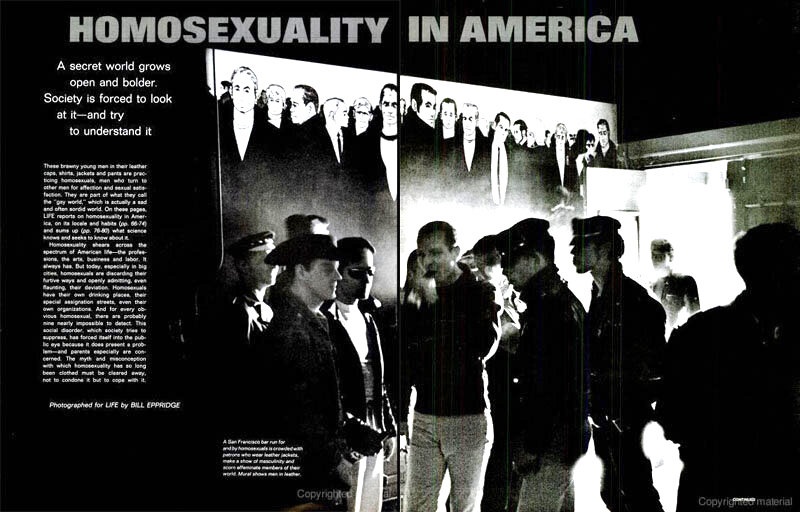

The June 26, 1964, issue of Life magazine (opening spread is pictured above) referred to San Francisco as the “Gay Capital of the World” and featured a photograph of the Tool Box, the first leather bar located in the South of Market area. The most celebrated element of the bar was a massive black-and-white painting depicting a variety of masculine, tough-looking men painted by local artist Chuck Arnett.

The June 26, 1964, issue of Life magazine (opening spread is pictured above) referred to San Francisco as the “Gay Capital of the World” and featured a photograph of the Tool Box, the first leather bar located in the South of Market area. The most celebrated element of the bar was a massive black-and-white painting depicting a variety of masculine, tough-looking men painted by local artist Chuck Arnett.

The Society for Individual Rights (SIR) was formed in September 1964, representing a newly assertive and self-confident liberationist attitude. In time the largest homophile organization in the country, SIR prided itself on being more democratic and inclusive than the Mattachine Society. The group would become a model for gay political organizations to follow. In April 1966, SIR opened the first gay community center in America, on 6th Street.

The Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH), the first gay religious organization, was founded in December 1964 by the Reverend Ted McIlvenna under the auspices of Glide Memorial Methodist Church with Daughters of Bilitis cofounders Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin participating. CRH was dedicated to bringing together homosexual activists and interdenominational religious leaders. In 1965, Citizens Alert, a 24-hour hotline supported by the CRH, was established to provide lawyers, photographers, and others to assist victims of anti-gay police brutality. When attendees of a New Year’s Day 1965 costume ball at California Hall, organized to raise funds for the CRH, were harassed by police, the ACLU took the case, which was dismissed—a turning point in the city’s gay rights movement.

Peggy Caserta opened one of the first hippie shops on Haight Street in 1965, a clothing store at 577 Haight Street at Ashbury. Calling her clothing store Mnasidika after a character in the ancient Greek erotic lesbian poetry collection The Songs of Bilitis so as “to appeal to gay women,” Caserta’s store became popular as the place to buy bell-bottom jeans, which were made by Caserta’s mother in Louisiana and flown into town. Caserta eventually struck a deal with Levi Strauss & Co. to manufacture its first bell-bottoms, which she sold exclusively for six months. One of her customers was Janis Joplin, with whom she became lovers. In the following year, Rikki Streicher opened a bar nearby, also in the Haight-Ashbury District, called Maud’s Study, which was said to be the world’s longest surviving lesbian bar at the time that it closed in 1989.

About 25 people picketed Gene Compton’s Cafeteria on July 18, 1966, when new management began using Pinkerton agents and police to harass gay and transgender customers. The following month, a police officer tried to grab one of the queens, who, refusing to put up with the manhandling, threw her coffee in his face. Angry queer people broke windows, threw dishes and trays at the police, and burned down a nearby newsstand. The next day, after Compton’s refused to allow drag queens on the premises, a picket line sprang up, and the newly installed plate glass windows were smashed once again. Following the riots, considered “the first known incident of collective militant queer resistance to police harassment in U.S. history,” activists formed C.O.G. (Conversion Our Goal), a network of transgender social, psychological, and medical support services that became the National Transsexual Counseling Unit, the first peer-run support and advocacy organization in the world.

When Gale Whitington, an employee of the States Steamship Lines, was fired in April 1969 for revealing his homosexuality in a Berkeley newspaper, a group of gay people formed the Committee for Homosexual Freedom (CHF), which picketed the company’s offices, becoming the first gay liberation group in the Bay Area. The next month, Tower Records fired Frank Denaro, believing him to be gay. The CHF picketed the store for several weeks until Denaro was reinstated. The group also ran similar protests at Safeway stores, Macy’s, and the Federal Building.

On Halloween night 1969, activists gathered outside The San Francisco Examiner building to protest anti-gay articles that had been running in the daily newspaper. Like other papers around the country, The Examiner had a policy of printing the names and addresses of men arrested in gay bar raids or in tearooms. Purple printer’s ink was dumped from the roof onto the peaceful demonstrators, who used it to scrawl “Gay is Good,” as well as other slogans, and to slap imprints of their hands onto the surrounding buildings. A riot ensued after police moved in, and the event became known as “Friday of the Purple Hand.”

These events represent only some of the highlights in San Francisco’s vibrant queer history, and each one merits much more investigation. Many of these events have been depicted in books and films. My goal here has been simply to enumerate some of the more outstanding moments in LGBT history in the hope that readers will investigate further on their own.

Jim Van Buskirk was the program manager of the James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center at the San Francisco Public Library (1992-2007).