I remember the day in eastern Montana, 1984, when I first understood that I could be killed for being homosexual. Being gay wasn’t an existence for me yet, but I knew who I was. I had little hope for experiencing it. The rural cowboy town I called home had a population that hovered around 4,000. Ninety-five percent of its residents identified as white, and one hundred percent were assumed to be heterosexual.

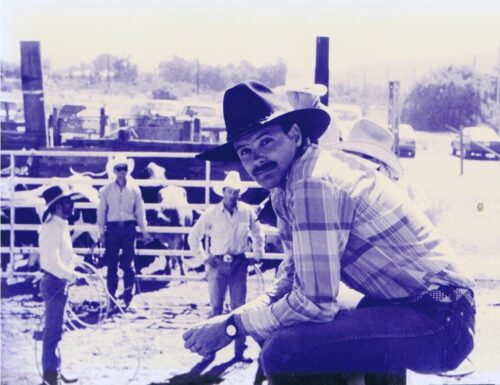

I was still rodeoing, but had given up bull riding. During hunting seasons, a hunting rifle was hanging on the gun rack in the back window of my truck. Being murdered didn’t seem likely, if I could successfully conceal that I was gay. If unsuccessful, ostracism was a certainty. Gay men and women didn’t survive small-town life in the American West without fear.

Not that I had any hopes of meeting a man like me. I was certain that there were no other gay men like me. I had been indoctrinated in the belief that all gay men wore women’s clothes, and that most lived in San Francisco or Hollywood. I desired what I knew, which was a rural, masculine man who could do physical things and lift heavy objects; a man who could get dirty, who could kill his own deer; a man like me, who desired another man like me; a man who I did not believe existed. I even questioned how I could possibly be homosexual.

That year, at 20 years old, I drove to the city of Billings to visit an eye doctor who could dispense contacts. There were no optometrists in my town. Unexpectedly, I discovered an adult bookstore. I went in, of course, hoping to see something, anything, that showed a man with his clothes off.

The bookstore’s selection of gay magazines was shockingly more extensive than I had imagined; I perused many. One showed men hanging out in a rural irrigation ditch, wearing leather paraphernalia that I could neither identify nor find purpose for: leather armbands, leather strappy things that went over their shoulders, chaps without pants. The only leather I owned, other than cowboy boots, were my bull riding chaps. I assumed the men in the magazine were bikers, like Hells Angels, except they didn’t look like Hells Angels. They were clean-cut and toned. I didn’t find them particularly erotic. I couldn’t imagine any purpose for their leather accoutrements, or why a gang of motorcycle riders needed such things. I just wondered how a gay porn magazine had convinced a group of bikers to hang out naked in an irrigation ditch.

I bought an Advocate magazine and scoured its contents. Most stories focused on the urban lives of gay men and women who had the nerve to be visible, and it referenced gay life in cities like San Francisco and Hollywood; but I failed to connect with anything it printed. It did not represent me.

It did have a massive selection of personal ads, organized by state. While there were none from Wyoming or Montana, where I had grown up, it gave me a glimmer of hope. This is how gay men could meet, apparently—through ads in the Advocate personals.

A few weeks after I posted an ad, I received a phone call from Dan who was a cattle rancher in North Dakota. He was in his thirties, single, and lived on the ranch that had been in his family for generations. His brother was married with children and his parents were still alive. All resided on the ranch property. Dan called me around midnight.

That made sense to me. Gayness belonged in the dark, I thought. Neither Dan nor I had ever fully consummated sexual activity with another man. I received two midnight phone calls from him.

Weeks later, I found the nerve to call him back at dinner time. I had to remind him of our previous telephone discussions of sex. He claimed that he must have been drinking. I never called him again, and wouldn’t pursue a man who could only be gay when drunk.

I soon drove back to the Billings bookstore when I realized it was a safe place for men to meet men. That’s how I met Al. Rugged and masculine with a fantastic moustache, Al worked in the oil fields, like me. He had grown up in the little town where I lived, but had moved to Billings a decade earlier. He had left our town, he said, when he became certain that he would either be killed, or his parents’ home would be burned down, if he stayed. The same would happen to me, he said, if I didn’t get out.

Al came back to visit his parents a few weeks later and spent a half hour in my basement apartment. He was uncircumcised, and felt the need to disclose this before we took our clothes off. I had the barest inkling of what that meant. Apparently, he said, some gay men didn’t like uncircumcised penises. I wasn’t one of them. The thought that there could be any preferences for penis specifics hadn’t yet occurred to me. I was dumb as a post, when it came to sex. He embraced me when I shook with fear for what we were doing.

Al and I never spoke, or met, again. I was too young. Too inexperienced. Too terrified. Too risky, for him.

In that same year, a man who was neither a cowboy nor of a rural background, arrived in town and opened a hair salon. His shop always seemed empty. He had no customers that I was aware of. I went in for a haircut, just once, and decided that he was most definitely gay. Perhaps he wasn’t. What the hell did I know? He seemed slightly effeminate, to me, light in his loafers, as I would later hear a man like him described. Men of that type did not exist in cowboy country. If this man was a homosexual, he needed to be more invisible, like me, I thought. I worried I could be seen by friends as I left his place of business.

He lasted less than six months. His storefront was soon emptied and I assumed he abandoned our town because he didn’t feel like he belonged.

As would I. In 1985, I sold my horse and moved to California. The lies and maneuvering it would require to exist in eastern Montana didn’t seem possible. I had turned 21 and couldn’t imagine any form of life that could exist for me, there.

A few years later, I met Lee Kittelson at a rodeo in California. Lee had grown up in eastern Montana, only thirty miles from where I had once lived. He had also moved to California, and we roped together for a couple of years.

Lee died during the AIDS epidemic, and it’s been forty years since my phone call with the rancher in North Dakota who could only ‘be gay’ when drunk. I’ve thought of him often since then. What was a man like him to do? Be the first generation in his family to leave the ranch and move to San Francisco? What kind of courage, or desperation does it take for a rural man who only knows agriculture and ranch life, to leave? Did he ever find it?

Today, if asked, I would describe myself as a happily-married gay man who raises great tomatoes and melons on my farm. I shot a nice buck last year, and I can still handle a rope just fine when branding calves. I no longer think I need to be invisible, nor do I live in fear, but I had to leave rural Montana to get to that place and meet someone new along the way.

Scott Terry is a gay cowboy and author of The Gift– a fiction novel scheduled for release in February 2025. His memoir, Cowboys, Armageddon, and The Truth: How a Gay Child was Saved From Religion was named Best Gay Non-Fiction and Best Gay Debut by the Rainbow Book Awards.

Discussion2 Comments

Scott, thanks for sharing your perspective. Glad you were able to make a life for yourself where invisibility is not required. We owe it to ourselves–no matter the challenges–to seek happiness however we define it. Keep farming those tomatoes and melons and sharing your story. It’s important for younger gay men and women to see that fulfilling lives are possible, coming in various stripes and colors. Michael Varga http://www.michaelvarga.com

Hey Michael….I agree. The Rainbow Tent is a big one, and it’s important to show that we exist in so many ways that others aren’t expecting. Whether it be bull riding, farming, or Peace Corp life (you), we exist and it’s important to be visible. Thanks!