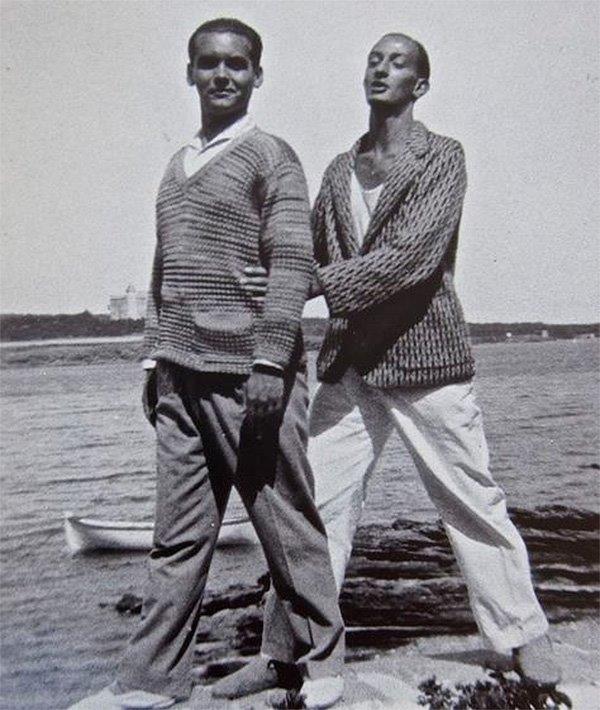

IN THE HEART OF MADRID, amid the vibrant cultural hub of the Residencia de Estudiantes, fate orchestrated a meeting in 1923 that would forever alter the trajectories of two towering figures in Spanish culture: Federico García Lorca (1898-1936) and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989). Lorca would soon become one of Spain’s most important writers and poets and a universal queer icon with timeless classics such as Blood Wedding (1933) and The House of Bernarda Alba (1945). Dalí would turn into a world-renowned surrealist painter. This is the story of their extraordinary relationship, an impossible love story for the ages.

Having been born just three years after the Oscar Wilde trials, which imprinted homosexuality on the social consciousness of Europe, Lorca struggled with his sexuality, which became a constant source of anguish. As a youngster, a teacher called him Federica for not being boyish enough. At the age of twenty, he wrote to a friend confessing that “in the presence of others I feign a sexual leaning that isn’t in my heart’s truth.”

Lorca grew up at a time when homosexuals could be imprisoned in Spain for up to twelve years. This changed dramatically under the 1932 Republican Penal Code, which only penalized homosexuality in cases of abuse. Spain’s social reality, however, didn’t live up to the new legislation. When Lorca became the artistic director of La Barraca, a theater group that brought classical Spanish plays to rural audiences, a right-wing critic called him “a faggot surrounded by a nest of homosexuals.” It’s no surprise that Lorca always dreamed of leaving Granada and Spain’s suffocating sexual morality.