On Halloween night in 1991, the doorbell rang, and it was Bruce. He was excited and hurried in to tell me to get ready because he had enrolled us in a Halloween competition at the After Dark in Monterey. I said I didn’t have a costume, and suddenly, as if out of thin air, there appeared two large, colorful flowers. Bruce said, “I made them, and you just need to wear black, but hurry; it’s almost time for the competition.” When we got to Lighthouse Avenue, we parked and placed these enormous flowers on our heads. He gave me two branch petals, and we walked into the bar. Everyone turned to look and, for a moment, it was exhilarating. Soon the competition started, and we were third to go up onto the stage. At that moment they were playing Madonna’s “Vogue,” and Bruce and I started to vogue using our petals. The crowd applauded and laughed, and like a miracle, we danced on stage as if we had rehearsed these moves for several days. We were awarded second prize, but for several days thereafter I felt we had won first prize. I believe we received a check but can’t remember the amount; I just remember that wondrous night at the After Dark.

Bruce was diagnosed with AIDS a few years prior, in 1989. His partner, Richard, would travel with him from Monterey to San Francisco to obtain care, and when he returned from these visits, he would tell me all the stories of his treatments, the people he met, and the new therapies he received. When he started taking AZT, we all felt hopeful, but that hope did not last long. Bruce did not respond well to the drug, but never once told me he was scared or angry. As his illness progressed, I wanted nothing more than to help him, but felt inadequate to do so. Bruce was hospitalized and released so many times in that period that I lost count.

During one of those visits, I arrived late to the hospital and heard a loud wailing. It was coming from Bruce’s room, and I heard his partner, Richard, sobbing uncontrollably by Bruce’s bedside. I hesitated to enter the room, feeling frightened. I realized at that moment I had lost my best friend. When I did enter, I saw Richard lying next to Bruce on the bed, holding him tightly and sobbing. All I could do was stand and wait. When Richard composed himself, he asked if I could drive him home because he was not able to drive. I said yes, and before I left the room, I looked at my friend, who was almost unrecognizable from when we first met. His life had just come to an abrupt end, and I was unprepared for the void it caused in my life. My friend was gone at age thirty. I gently kissed him on the forehead and took a deep breath, and walked out of the room holding back my tears. A few days later, I dreamt about Bruce and my dog Beau, who had also recently passed away. Bruce appeared in my dream, and I asked, “What are you doing here?” He said, I have a surprise to show you, and then Beau appeared. He was wagging his tail. Then Bruce waved, and they both walked away, causing me to wake up. Bruce was happy, shining brightly as always, and he stopped to tell me that Beau was all right. Bruce was the first of many friends that would pass away quickly. Each time, the void I felt became bigger and bigger. And then, almost six months later, Bruce’s partner passed away driving home one night from work; he was killed by a drunk driver. I think Bruce missed Richard very much and wanted to be with him for eternity.

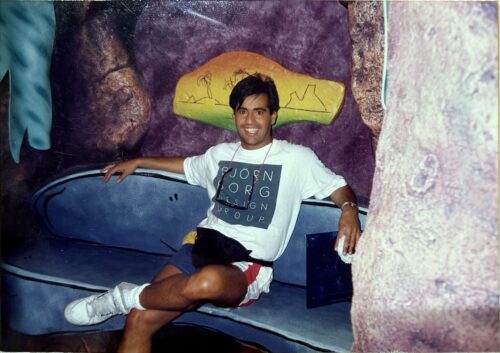

A few months after Bruce passed, I received a call from my cousin James, who was living in Miami. He told me he had been diagnosed with HIV. He cried, and I asked him what I could do. He was silent, and immediately I told him he had to come to Monterey to visit. When he finally came shortly after, I picked him up at the airport, and he looked like he had lost a lot of weight. Never did he talk about HIV or AIDS, until one night in San Francisco after taking mushrooms and dancing all night; we came back to our hotel room, and he told me that when he dies, he wanted me to call his parents and send his mother a Mother’s Day card, which I told him I would. I asked him if he regretted anything. He replied, “Nothing.”

James and I had had so many crazy escapades in our lives, and our time together was always filled with adventure, sometimes chaos. We talked about our childhood until the sun came up, the friends we had known and lost, and life in general. Little did I know this would be the last time I would physically spend time with James. Soon after he was hospitalized multiple times, and each hospitalization became a long-distance telephone call. He felt isolated, and for the first time ever, I felt he was lonely. Although his family and friends visited, he knew that time was not in his favor. I did eventually fly to New York to visit him in the hospital. He had a tumor in his brain, and was undergoing radiation only to keep him comfortable. James’ light had vanished. The spontaneity and the joy were gone. Soon after my visit, he was moved to hospice, and he passed away a month later. I did not attend the funeral. I just could not say goodbye. Like with Bruce, James’ death left a black hole in my life that would take many years to fill. And I lived with survival guilt. I had done everything James’ and Bruce had done, but I was not sick. It took some therapy to resolve this guilt, and I still think about them both. They still live within me, but I can’t pick up the telephone to talk to them except in my mind. Every now and then something will happen, and I will say to myself: if only James and Bruce could have seen this.

Every now and then, I am reminded of many old memories with them, and I start to sob. I don’t know why, except the light seems to flicker much more now that I am 62. I have so much to be grateful for, but the darkness surrounds me so intensely that I can’t find my way out. I keep looking for Bruce’s beacon and James’ light. I know I need to create my own light, but it would be so much easier if they were still around to take me on one of their adventures.

Héctor Vizoso is an essayist and retired Nursing Director and AIDS researcher having previously published in peer-reviewed nursing and medical journals. His essays offer deeply personal insights into real-time events and the people who have shaped his life. In this essay, he reflects on the long-lasting trauma of the AIDS epidemic, a theme he further examines in Night Shift, published in the American Journal of Nursing (2022) which won an APEX award in 2023.

Héctor Vizoso is an essayist and retired Nursing Director and AIDS researcher having previously published in peer-reviewed nursing and medical journals. His essays offer deeply personal insights into real-time events and the people who have shaped his life. In this essay, he reflects on the long-lasting trauma of the AIDS epidemic, a theme he further examines in Night Shift, published in the American Journal of Nursing (2022) which won an APEX award in 2023.