In a speech given to the Ohio County Women’s Club in Wheeling, West Virginia on February 9, 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy asserted that the U.S. State Department was riddled with traitors—205 members of the Communist Party. Granted, fears about the hidden danger that communism posed to American institutions were not uncommon during the early years of the Cold War. Three years before McCarthy’s speech, in 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) held widely publicized hearings on the spread of communism within the motion picture industry, leading to the blacklisting of a number of well-known Hollywood figures. But McCarthy’s public comments, which made national headlines, lead to Congressional and Executive actions that eventually resulted in a nearly quarter-century ban on gay men and women serving in federal government, and upwards of 10,000 men and women losing their jobs. In his 2004 book, historian David K. Johnson refers to this systematic federal persecution of gay men and lesbians as “The Lavender Scare.”

Shortly after McCarthy’s infamous speech, senior officials from the State Department testified to the Senate Appropriations Committee that 91 persons of “shady character” had been fired as security risks; upon further questioning, the officials acknowledged that most were homosexual. From daily newspapers to tabloid “tell-all’s,” media reinforced the notion that homosexuals were unfit to serve in government. Robert Roark, a syndicated columnist for the Scripps Howard Newspaper Alliance warned that homosexuals “travel in packs” and were prone to blackmail. On April 19, 1950, the nation’s newspaper of record, the New York Times, published an article with the headline: “Perverts Called Government Peril; Gabrielson, G.O.P. Chief Says They are as Dangerous as Reds.” In his book, The Lavender Scare, Johnson opines that “the constant pairing of ‘Communists and queers’ led many to see them as indistinguishable threats.” Recurrent media attention served to amplify concerns across the general public that any homosexual employed by government posed a serious threat to American security.

Johnson’s book provides extensive details about the various Congressional actions and concomitant media hysteria that led up to President Eisenhower’s 1953 Executive Order (EO) instituting a ban on gays and lesbians serving in federal government. Excluding communists and those affiliated with “suspect” organizations from federal employment wasn’t new, but the 1953 EO expanded its exclusionary criteria, citing “immoral, or notoriously disgraceful conduct, habitual use of intoxicants to excess, drug addiction or sexual perversion” as bars to federal employment. While initial concerns about homosexuals posing a substantial security risk had distinct partisan overtones (McCarthy and his colleagues accused President Truman’s administration of failing to recognize the seriousness of the supposed threat), by the time the EO was signed by President Eisenhower, there was broad bipartisan support for the policy of denying gays and lesbians federal employment and removing those homosexuals who already held jobs.

Readers may be surprised to learn that it wasn’t until 1975—six years after Stonewall—that the U.S. Civil Service Commission ended the ban on gays and lesbians in federal civil service; two years later the State Department followed suite regarding employment in the Foreign Service. But by then, these actions had resulted in an estimated 5,000-10,000 resignations or firings and unrecorded thousands of well-qualified men and women who avoided applying for jobs within the federal government because of their sexuality. In some instances, the negative consequences were even more profound; an unknown number of those who were under investigation or fired because of allegations of homosexuality committed suicide.

The lavender scare is a pluperfect example of what sociologists refer to as a “moral panic,” that is, when a perceived threat is blown out of proportion and becomes widely acknowledged as a serious danger to physical safety or to society’s values. Responses to moral panics typically result in legal and policy actions that are aimed at countering the perceived threat. Recent anti-LGBTQ legislation and policy directives coming from federal and state governments highlight America’s most recent moral panic, which has a particularly keen focus on issues of gender and gender identity.

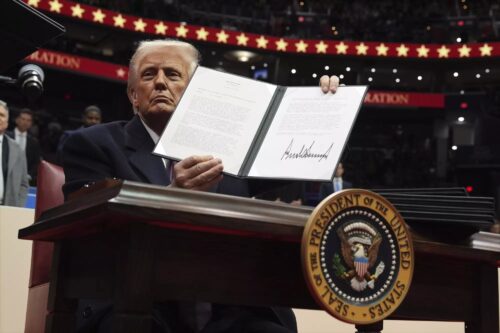

A series of Executive Orders coming from the new administration target transgender and non-binary persons in ways that threaten their health and well-being. The first EO, issued on January 20, 2025, explains that the federal government recognizes two sexes only, male and female, which are established at birth and “are not changeable.” To comply with the order, federal websites removed references to and information about transgender persons and their unique health care needs. After judicial action, some of this information was restored, but with the prominently posted caveat that “this page does not reflect biological reality and therefore the Administration and this Department rejects it.” In a move that can only be described as “Orwellian,” the National Park Service, in response to the EO, removed all references to transgender and queer persons from the Stonewall Inn National Monument website. This, despite the fact that histories of the June 28, 1969 event indicate that Marsha Johnson and other non-gender conforming persons were actively involved in the uprising.

Then, on January 27th of this year, the White House released an EO barring transgender men and women from serving in the armed forces, stating that “expressing a false gender identity divergent from an individual’s sex cannot satisfy the rigorous standards necessary for military service.” This was followed, one day later, by an executive order banning federal funds from being used to support gender affirming care for minors. Ignoring scientific evidence that shows improved mental health outcomes among children and young adults when their external appearance becomes more congruent with their felt gender identities, the order callously refers to gender-affirming hormone care as “chemical mutilation.”

Other actions coming from the White House, like the ban on federal funds being used to support awareness of and training for diversity, equity, and inclusion, bespeak antipathy toward understanding and responding to the unique health and social needs of minority populations, including sexual and gender minorities—not to mention communities of color. While many of the actions referred to herein have been temporarily blocked by court orders, their intended outcomes—and the resultant damage they have and will continue to cause—cannot be ignored.

Will government continue to discriminate against persons whose gender identities do not match their sex at birth? Or will gender minorities and their allies succeed in educating legislators and other elected officials so they come to understand that variances across sex and gender aren’t dangers posed by threatening outsiders; instead, they are genuine and unique expressions of the diversity of humanity. It’s worth remembering that in response to the governmental oppression of the lavender scare, same-sex loving men and women learned how to organize and challenge discrimination, laying the groundwork for the gay liberation movement of the 1970s. One hopes that the current moral panic over gender identity and transgender rights might follow a similar, albeit much more rapid, trajectory.

Ronald Valdiserri is a physician who has spent most of his professional career working to prevent the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, first at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and later at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In addition to his numerous medical and public health publications, he has authored a collection of personal essays about AIDS (Gardening in Clay)and published several poems. He lives in Georgia with his husband of many years, Ray.

Ronald Valdiserri is a physician who has spent most of his professional career working to prevent the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, first at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and later at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In addition to his numerous medical and public health publications, he has authored a collection of personal essays about AIDS (Gardening in Clay)and published several poems. He lives in Georgia with his husband of many years, Ray.