My older sister has been a devout Jehovah’s Witness for almost fifty years. The world has changed a lot in those years. So have I. So has my sister. And so, to this observer, have the Witnesses themselves … at least in their views on homosexuality.

In the 1980s, when I came out and bought a home with my then-partner and now-husband, my sister mailed a Jehovah’s Witnesses pamphlet to me describing homosexuality as an abomination.

We took the cover off our backyard grill, doused the pamphlet with lighter fluid, and set it aflame. My husband cheered. I watched in stunned silence. I had always looked up to my sister, nine years older than I. But on that day, a chill descended on our relationship. A chill that took a long time to thaw.

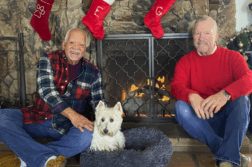

Fast forward nearly four decades from that incendiary event in our backyard, and you’ll find my husband and me on one of our frequent visits from our home in Atlanta to Northern California, where my sister lives in a nursing home. She is eighty-one years old. A recent stroke has left her right side paralyzed. Once a great conversationalist, she struggles with aphasia, severely curtailed speech.

On those visits, we have found rewarding friendships with numerous members of my sister’s JW family. And the rift between my sister and me is healing.

“I love you,” she says. “So good to see you. Good for the soul.”

It’s good for my soul, too. We sing old songs together. “When You’re Smiling” is a favorite. Though she makes only limited conversation, she impeccably remembers lyrics, and reads aloud from the books I bring her. At mealtime, I lift small forkfuls of food to her mouth.

Her brothers and sisters in the faith invite my husband and me to dinner in their homes, treat us to meals at nice restaurants (where we laugh and chat away the hours until closing time), give us gift cards to the local Peet’s Coffee shop, and recommend great hiking trails.

They do everything but preach at us. In fact, we don’t hear the slightest suggestion that they find my husband and me … or our nearly fifty-year relationship … an abomination. Instead, they’ve accepted us as equal members of the care team for my sister, who was widowed in 1982 and never remarried. Because of her love of Northern California and her strong network of friends in the denomination, I can’t imagine moving her to Atlanta. Her friends’ frequent visits to the nursing home, their updates to me on my sister’s condition, and their Zoom calls are making the situation work. My sister is content.

In short, I love these Jehovah’s Witnesses for their efforts. Whew! I never dreamed I would say that, because for many years I believed the Witnesses stole my Big Sis from me.

To backtrack—I have always loved my sister. While she was a Pan Am stewardess (that was the term for ‘flight attendant’ in the 1970s, and she was proud of it), she took me to London to celebrate my high school graduation. It was great fun.

In my college years, when we both came home for Christmas, we stayed up till the wee hours of the morning, sharing a bottle of wine and talking about everything … except my homosexuality, of which I had grown fully aware in college. Though I confessed my feelings to no one and had limited sexual experience, I trusted that my sister would be my confidant should the time come to share my truth.

A few years later, when she announced to our family that she had become a Jehovah’s Witness, I felt like Charlie Brown when Lucy pulls the football out from under him.

What had happened to my cool, sophisticated sister? How could she be one of those annoying door-to-door proselytizers? Not celebrate Christmas? Or birthdays? Believe we were in the end times? Our family was mainstream Presbyterian, for heaven’s sake. How had she become so extreme?

I told myself that she must have found a sanctuary in her newfound faith. I could only imagine that something, or several somethings, had caused her to turn from her jet-set life to a quieter one, with people whose feet were planted firmly on the ground.

Whatever the reason for her conversion, it’s a fact that I must accept. And accept it I finally have.

I acknowledge that she might not have intended the pamphlet to hurt us all those years ago, but simply to offer some big-sisterly advice against the backdrop of AIDS, which was a scary reality in American life in 1988, the year she sent the pamphlet. And I continue to seek the common ties that bind us. In my memoir, I write how important “a family beyond my family” was when I came out, the allies who embraced me when my biological family pushed me away. Hadn’t my sister done the same with her brothers and sisters in the faith—found a family beyond our family?

You might say that I have caved to the opposition, but I don’t see it that way. Rather than the white flag of surrender, I see it as a simple handshake—the acknowledgment that even in tough circumstances, we can form bonds and break bread with those outside our immediate circle. We need more of that in these divisive times.

Jehovah’s Witnesses continue to “disfellowship” non-repentant queers and other members of their congregations who don’t follow the rules, but the denomination’s website makes it clear today that “the Bible doesn’t promote hatred of anyone—gay or straight. Rather, it tells us to ‘pursue peace with all people,’ regardless of their lifestyle…. So it’s wrong to engage in bullying, hate crimes, or any other type of mistreatment of homosexuals.”

Still, at seventy-one, I’ve learned that we can’t have everything. Instead of arguing with or turning our backs on people who have different beliefs, perhaps the best thing my husband and I can do is to be us—a real-life example of a decent, ordinary gay couple. Maybe that is our best tool for changing hearts and minds.

Meanwhile, we are planning a return to Northern California soon. And we already have a winery visit on the books with one of my sister’s closest friends.

“Let’s do something fun,” she said.

Who are we to say no?

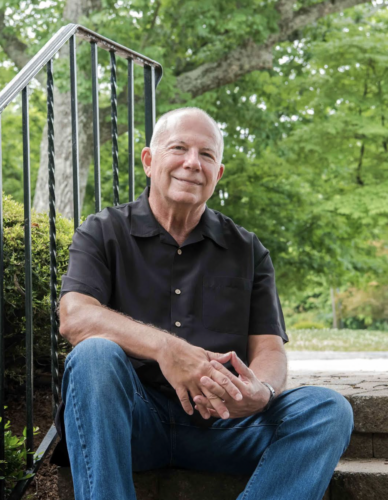

Mike Coleman and his husband, Ted Brothers, have been together for forty-seven years. Mike’s memoir, The Way from Me to Us, tells their story against a backdrop of major change in public attitudes toward LGBTQ people. Published by Riverdale Avenue Books, it was a finalist in the Chanticleer Journey Awards for nonfiction about overcoming adversity—in Mike & Ted’s case, homophobia of the internal and external varieties. A professional writer for nearly 45 years before retiring in 2020, Mike blogs extensively about his and Ted’s travel adventures from their home in Atlanta. For more information, visit his website here.

Mike Coleman and his husband, Ted Brothers, have been together for forty-seven years. Mike’s memoir, The Way from Me to Us, tells their story against a backdrop of major change in public attitudes toward LGBTQ people. Published by Riverdale Avenue Books, it was a finalist in the Chanticleer Journey Awards for nonfiction about overcoming adversity—in Mike & Ted’s case, homophobia of the internal and external varieties. A professional writer for nearly 45 years before retiring in 2020, Mike blogs extensively about his and Ted’s travel adventures from their home in Atlanta. For more information, visit his website here.

Discussion4 Comments

I’m glad and somewhat surprised to see there has been some evolution about the topic of homosexuality from the Jehovah’s Witnesses. My last direct contact was when they came proselytizing about 30 years ago and I said, “You’re knocking at the wrong door, I’m afraid. We’re going to be burning in hell in this house.”

Now, in my East Hollywood neighborhood, we often see a little group of them on the corner every Saturday morning. I don’t know how they actually gain converts, and it looks tortuously boring. Often enough, the only young person in this group is an adolescent boy in his early teens. I notice how pressed his white shirt and pants are, how well-knotted his tie is, how meticulously combed his hair. There is no doubt in my mind of the inner conflicts he is already probably facing, and how difficult his road ahead will be.

So true. If that young man you see is LGBT, his turmoil is enormous. I was one of those kids….a teenager going door to door for my faith, yet knowing I was the abomination the Jehovah’s Witnesses detested. I always hope that all of those children who are forced to spend their lives proselytizing for the Jehovah’s Witnesses, find a way out.

This was really a nice story to read, and I am happy that Mike Coleman found a way to re-kindle a relationship with a Jehovah’s Witness family member. It’s also nice to read that his sister’s friends have evolved enough to include Mike and his husband in their social interactions. The key element that is missing from Mike’s experience, and is so common to those of us who left the religion and are gay, is that Mike was not raised a JW, and did not leave. That alone is enough, in the eyes of the JW religion, to label one as an “apostate” and is accompanied by punishment. JWs are prohibited from socializing with apostates. Being gay and daring to leave the faith will result in a very different experience than Mike had. I would not be able to rekindle a relationship with my family members who have written me off for decades, simply because I am gay and abandoned the JW faith, but it is very heartening to read that Mike and his husband did. Sometimes people do find a way to forgiveness and acceptance.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses have not changed their view about the LGBT+ community. It is the exact opposite. The Governing Body continues to double and triple down on its position. They call same-sex marriage an abomination. Stephen Lett went as far as to say that homosexuals will be resurrected as homosexuals and will be given the chance to change their ways. They will be given 100 years to do so or be destroyed.