While the events described here took place over a year ago, the story is not over by any means, as the victim is still in recovery and a trial is pending. Also, when it was reported it made a big impression on me, and I’m still a little haunted by it.

On June 20, 2020, an eighteen-year-old gay man from Lafayette, Louisiana, was tortured and nearly dismembered by another young gay man on a Grindr date during Pride Month. His name was Holden White.

Holden’s story haunts him.

Since the attack, cold water is no longer the trigger that it used to be. The sight of knives, however, still is. One year into the pandemic, two emotional therapy pets, and several Billie Eilish hair evolutions later, Holden is coping like any survivor.

For most of us, adulthood is a series of choices, a one-night stand or a bad haircut. For teenage Holden, adulthood would be condensed into the events of one fatal night and its aftermath. Instead of sharing his coming out story, Holden will likely tell his children that this was the event that shaped him.

On the night it happened, Holden White had a date with nineteen-year-old, Chance Seneca. Chance and Holden had met through Grindr and were casually chatting on and off for about a month. They had made plans to play video games at Chance’s family’s house after Holden got off work.

Holden had been looking to date someone that was in his words, “not flamboyantly gay.” Chance was a Lafayette townie with bleach blond hair and piercings. Holden had trophies in his room for acting and was a rising sophomore in college. When he got his septum pierced, Holden would send Chance a picture; Chance replied, “cute.” After the attack, Holden had to remove the piercing to go through the MRI.

They had never met in person. Holden had not yet seen Chance’s Facebook profile picture of the serial killer, Jeffrey Dahmer. Even if he had before their date, Holden is too young to remember Dahmer’s reign of terror on gay men.

Holden was left to his own devices at home and like many of us was not immune to the loneliness and the boredom, an unseen but potentially dangerous side-effect of the quarantine. Thankfully, when the night quieted and the mosquitoes descended, Holden could scroll through a sea of possibilities on his phone. The headless torsos, duck lips, shirtless bodies, vacant stares are all a strange but normalized part of dating apps.

Many victims like Holden are blamed in hindsight for not meeting their online dates in public. However, other gay men from the Lafayette area, like Sami Sion, acknowledge Holden’s dilemma. “It is easier to go on dates in someone’s car in a sketchy cane field than face the small-town scrutiny in a movie theatre or a diner. It is the long tradition of gay people to date in private.” Despite the dangers, this demographic greatly relies on dating apps for their acceptance, especially in the Deep South.

Holden had thought he was safe; he was dating a Lafayette boy, albeit one who was into kink. Holden is not someone who binges the ID Channel, so he could not see the possibility of a stranger asking to pick him up in handcuffs to fulfill a cop-criminal role-playing fantasy as a potential red flag.

What followed was the fodder of horror movies. The blanks in Holden’s memory would later be filled by police and emergency responders. Holden, upon arriving at Chance’s family’s home was marched into the bathroom with a gun held to his back and then strangled from behind. We learn that Holden was rendered unconscious from the strangulation and had suffered blunt force trauma to the head.

It was touch-and-go that first week in the hospital. Holden was in a coma for the first three days. He had to have emergency surgery on his wrists. His doctor would tell the press that it was the worst case of wrist wounds he had seen in his fifteen years as a surgeon. Through physical therapy, Holden has gradually regained almost full function back in his dominant hand. He may never fully recover the full use of his other hand, yet he continues to push forward and occasionally sends me pictures from his drawing class. By that point, COVID had made visiting complicated, so Holden’s older sister Faith relied on their parents to FaceTime from the ICU with any updates on her brother.

She posted updates daily on her Facebook with the #justiceforholden. In a matter of days, Faith raised their quota of $100,000 for the GoFundMe for Holden’s medical and legal bills. There was overwhelming support for Holden both locally and internationally with “kisses from France” and “hugs from Belgium.” It was due to Faith’s rapidly fired social media campaign and the local chapter of PFLAG that the FBI enlisted their help. The local news had already likened the attack to a hate crime, yet the local police department had ruled out the possibility of a hate crime within 24 hours. They had also failed to provide the hospital with a rape kit. Currently, the federal trial is set for 2022 and Chance Seneca is looking at a six-count indictment including the charge of a hate crime, which has already been certified as “complex.”

After the attack, Holden had to cultivate a new normal. In between going to school and working, there were appointments with doctors, the FBI, lawyers, the police, and the media. When he returned to the dating game, he was no longer Holden but “the boy who almost got murdered.”

There was also the victim shaming both from loved ones and on an institutional level. His doctor, upon giving him his annual physical, commented on his new injuries by saying, “Did you learn your lesson?” The online trolls and their death threats did not help; neither did the police referring to the attempted murder as a “lover’s quarrel” or the press’s reference to Holden in the past tense. Holden had to find other ways to take back his narrative, so when his wrist casts came off, the ink came on. He enjoys telling people what the tattoo on the inside of his wrists represents: the colon represents a sentence not yet ended and the fletching arrow reflects his path moving forward.

Holden’s life must have felt like a circus those first few months with everyone vying for a piece of him, his story. I can only imagine the intensity of the flailing of wings, beaks, and claws with such proximity to his face. Then after the ravaging, at the center of it all is the loudest silence with the realization that the vultures have moved onto something else. New information creates new buzz with headlines like “Jeffrey Dahmer,” “Cannibal,” and “Hunting Grounds.” Potential TV rights create new chum.

I learned the other day that it is a great misconception that vultures circle dead carrion. In actuality, vultures canvas for potential food. Their perseverance is annoying but effective. As a writer, I was able to dust off the maggots and repackage this piece into something the world would find appealing enough to bring back to their nests. I shine my light into the divots. I poke holes and people are reminded that internalized homophobia is real, that LGBT people are at constant risk, and that prosecuting hate crimes can boost morale for the victims.

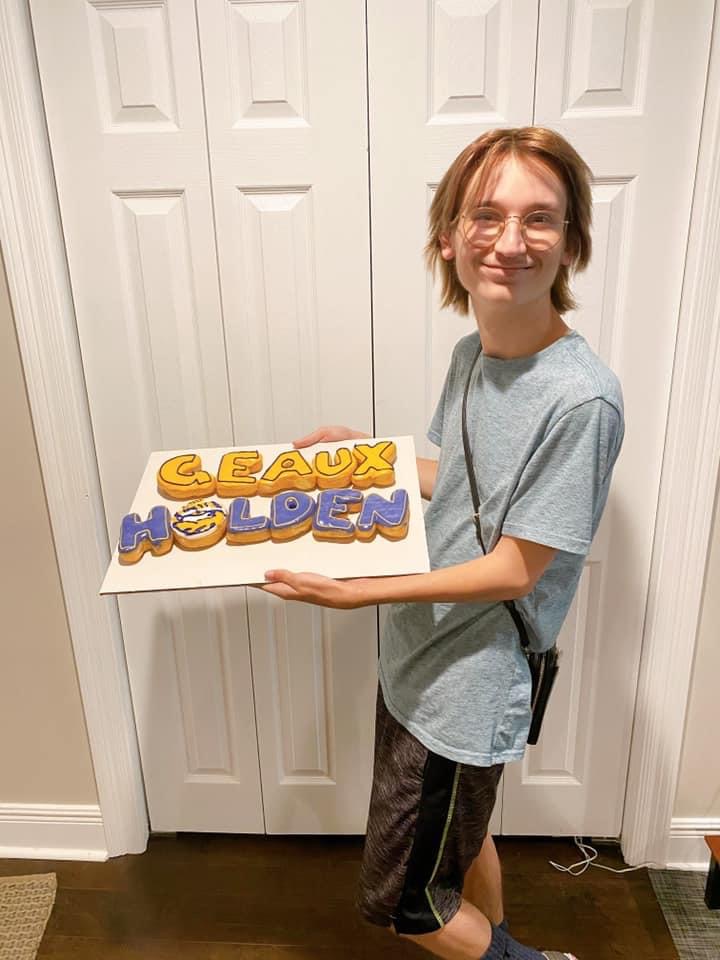

I do withhold one piece that shouldn’t be exploited, where normalcy begins to trickle back into Holden’s life —his nineteenth birthday, his registering for classes, and his re-learning to walk. These are the little but many milestones of any survivor and they are not carrion for the vultures.

Scarlett is a writer and co-host of the pre-launch, Louisiana true-crime podcast Missing Magnolias. You can visit the website here at https://www.missingmagnolias.com. Her writing has also appeared in Musée Magazine and Dead Mule of School of Southern Literature.

Discussion1 Comment

This short piece marks the emergence of a powerful new voice in non-fiction and documentary writing. Scarlett paints an indelible and deeply expressive picture of a forbidden subject, hate-crimes. Bravo!

More, please.