I’ve wanted to look up to a man since I was a boy. I suppose it was important because in the moments—and they were rare—when I was in the company of men or boys worthy of admiration, I felt at peace. My world seemed chaotic then, which no one dared to acknowledge. I could see evidence everywhere around me: a masked, gun-toting terrorist pacing on a balcony—a senator, rock star, and preacher assassinated at swank hotels, apartments, and on a balcony in Memphis. The world was going mad.

Movies were my escape, from the comedy of What’s Up, Doc? to whatever adventures played on TV—pirate movie classics on Saturday morning, John Wayne Westerns on Saturday night—including dramatic made-for-television fare. Early in life, I think I must’ve conflated characters and names from Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962) with Around the World in 80 Days (1956) and conjured a dashing foreigner named Jacques firing up in my imagination, ready to take my hand, pull me up, and take me to where everything was exciting and free.

I’m the youngest of four children. My inner state was one of joy, music, dance, and idealism amid the turmoil of the world outside and inside my home. Details don’t matter. Your story’s probably similar. I sought refuge from the chaos in straight-themed stories and songs on television, in movies, in stage musicals, in books, and a record player spinning 45s and 33s—even 78s playing ragtime and jazz. Today, though it might be called heteronormative, I don’t care because this was a wonderful world of my own making.

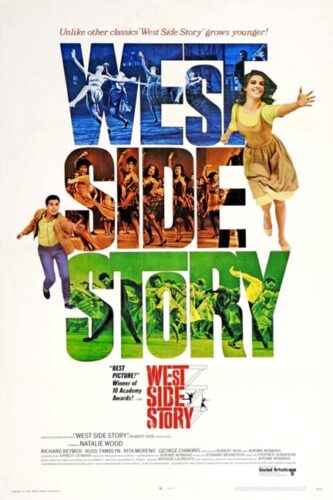

I was scared, often isolated and deprived. Cultural milestones let me mark progress; learn; steel myself; experience wonder, sorrow, and vulnerability; resolve; and grow. Watching West Side Story on television one night in color, movement, music, and lyrics, I discovered that true love could be at once gloriously stirring and ultimately doomed. Love between a woman and man could be as forbidden as what I felt inside, whether I was drawn to Riff, Tony, or Bernardo.

Throughout my youth, inspired by what I was drawn to in art, I concluded that love didn’t have to end. I sensed that romantic love endures whether between the same or the opposite sex. When Nellie Forbush sang of being “in love with a wonderful guy,” I knew this was a feeling I could have, too, and that mine could be about a man, whether a Frenchman, a Puerto Rican, or a cowboy galloping high on a horse.

After that, I began to understand that my same-sex attraction was real, pure and indefatigable, going deeper than lust. Straight culture affirmed that mine was a longing for abiding romantic love—not for the sake of suffering, aching, and misery, not as martyrdom or noble sacrifice—but as an achievable value in my lifetime. And that love was complex and worth thinking about. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s romanticism and promise of feeling lightness, of floating above the fray, imprinted in my consciousness and secured my self-esteem. I knew I could deserve to love and be loved. I knew I was good regardless of sexual orientation.

At times I struggled. Following a dark period of self-doubt, which could’ve driven me to suicide, I started to explore my convictions in earnest, reading works of philosophy by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Ayn Rand. I investigated various religions—visiting churches, temples and a reading room in search of a systemized, guided form of reverence based upon reason—while contemplating whether I was an agnostic or an atheist. I sought to learn and know the difference.

By the time I bought The Virtue of Selfishness in a bookshop when I was 15, Ayn Rand was winning the arguments in my head. I knew I was on the right track, though I also knew that being gay could make me an outcast. At my lowest point, I walked along a railroad and contemplated jumping in front of a train. This is about the time when I read Rand’s most powerful, biting, and poignant essays on culture and politics, which resonated with me. I came to realize that I wanted to live, though I knew I wasn’t prepared and didn’t know where to begin. Rand gave me the glimpse of a heroic future in which I could admire and look up to man—starting with myself.

Rand’s philosophy—egoism, individualism, and capitalism—provided the tools, framework, and blueprint with which to chart my course, though I knew life would be different than her larger-than-life fiction. This is about the time I discovered Ordinary People, Robert Redford’s 1980 movie version of Judith Guest’s novel about a family in the Chicago suburbs, where I lived. Redford’s film was a powerful depiction of a troubled boy with a loving, caring friend of the same sex—a non-sexual love—previewing how I could walk through and emerge from darkness. I began to dance to music and study philosophy, literature, and the arts. The music of Elton John, who was writing and recording songs about Marilyn Monroe’s innocence, unrequited love, and the assassination of John Lennon, who’d been singing about starting over, provided coded signals to pursue gay romantic love.

These themes were echoed by artists who sang with tenderness, sass, and bliss. I found encouragement in Jackson Browne’s triumphant “Hold On Hold Out” and Olivia Newton-John’s challenge “Have You Never Been Mellow”—a statement, not a question—both of which foster resilience in the face of the era’s tightening tension and increasingly ominous dark thoughts.

Works by Bob Fosse, Liza Minnelli, Bob Seger, Sammy Davis Jr., and Fred Astaire emboldened me. Each artist was dismissed or minimized by many within the gay subculture because they were straight. The sum total of everything—including TV programs such as The Andy Griffith Show, in which a policeman is the voice of reason and composure, or Father Knows Best, in which an insurance agent is nurturing, introspective, and kind in listening to his son’s deepest suffering—marked the way with guideposts reinforcing my notion of romantic love.

Except for the ebullient Liza, who was eclipsed by the maudlin legacy of her mother, none of the performers I admired were embraced by gay culture. So my sensibility was a counterpoint to their caustic, cynical, flamboyant antics or humor, their fetishization of Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand, and drag queens. As I came out and years went by, I learned that romantic realism as an approach to life is marginalized in gay culture by cavalier bitterness, sarcasm, scorn, and regret.

After working as a model and dancer, I began my journalism career in the early 1990s. I wrote for newspapers and magazines where I was prejudged for not being aligned with—or propagandizing for—leftist gay politics. One editor admitted she denied me opportunities after I declined to act upon her forceful nudge to become the newspaper’s “gay columnist,” a notion I found (and find) repugnant. I’m an assimilationist. Straight people saved my life.

Some of my editors were gay. I was out of the closet, so most of them knew I was gay. Throughout this time, whatever the course of my reporting, I rejected so-called identity politics, including the collectivist gay acronym in its earliest incarnations (I still reject it). So I did (and do) not use it in my writing. I am out, proud of myself, and living openly and explicitly as a gay man. With proximity to those who were or wanted to be in that milieu, I’ve pitched, researched, reported, written, and edited my stories and articles with the same values and verve I’d held since youth: realism, hope, and optimism that the ideal is possible here on earth.

I’ve learned over the decades that the world is still going mad—it’s going madder and darker—and yet here I am, still optimistic, hopeful, and realistic. I’m not less gay than anyone else. I dance every day (not that there’s anything fabulous about that). I love my life with every complication and challenge, including the burdens everyone knows—ageism, isolation, prejudice—and I’m proud of my work, including the gay parts. This storyteller’s story begins with the knowledge that almost everyone is striving to be happy. I know I am—being just as I am. As my story evolves, I know, too, that the man I’ve imagined is real—he’s “somewhere”—and he can be mine.

Scott Holleran’s writing has been published in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and the Advocate. His first book, Long Run: Short Stories Volume One, with a foreword by Ayn Rand biographer Shoshana Joy Milgram, debuted last fall. Read his non-fiction at ScottHolleran.substack.com. Listen to him read his fiction aloud at ShortStoriesByScottHolleran.substack.com. When he’s not writing, Scott Holleran dances, choreographs, and coaches wellness.