A cisgender writer explains the vital lessons he learned while writing about an overlooked chapter in transgender history.

I’M AN EXPERT at nothing and an outsider to everything. Simply put, I’m a writer. During my four decades as a journalist, novelist, and author, I’ve chased my fascinations down any number of rabbit holes, lured by curiosity, empathy, and compelling interest. I’ve spent months and years researching everything from open-water marathon swimming, to the mechanics of free-throw shooting, to the strange and wonderful world of competitive duck painting—just so I could write with authority about those things.

But that doesn’t mean I’m qualified to swim the English Channel, or consistently put basketballs through a netted hoop, or paint a credible greylag goose. I’m simply qualified to tell you about the people who do those things.

My outsider role was never more apparent than in 2017. I had just moved to Colorado, and for the first time began hearing about the tiny, remote town of Trinidad and the pivotal role it played in gender and medical history. For more than four decades between 1969 and 2010, the mostly Hispanic Catholic former mining town near the New Mexico border had been what The New York Times once indelicately called “the sex-change capital of the world.”

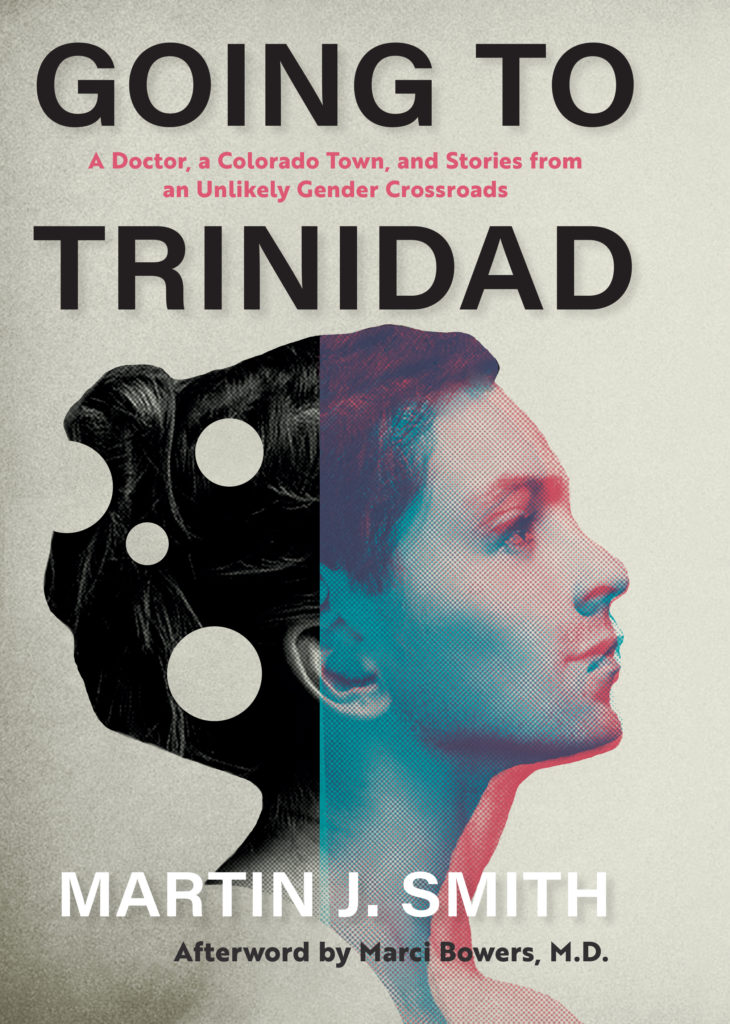

I wondered: How was it possible that no one had written that book? I began to do some research. The more I learned, the more compelling the story became. I wanted to tell the stories of Dr. Stanley Biber, the pioneering Trinidad surgeon whose work made “going to Trinidad” a euphemism for gender confirmation surgery; his transgender protégé Dr. Marci Bowers; and some of the approximately 6,000 medical pilgrims who came from around the world for relief from the pain of gender dysphoria.

Back in 2017, telling the Trinidad story seemed particularly urgent because the civil rights of transgender men and women were under direct assault. Maybe my book Going to Trinidad could help non-trans people better understand the individuals who were being persecuted.

But when word got out about my project, some within the LGBT community considered me unfit to tell the story. A transgender blogger from Brooklyn wondered why a cisgender male was proposing to write about this overlooked chapter in gender history. “Nobody I know in the trans world appears to know this person,” she tweeted to her followers. “Why should we trust [him]?” She strongly suggested I partner with a trans writer for this project, advice later echoed by a prominent LGBT editor at a progressive website who criticized everything about my proposed project, including my vocabulary choices in describing it. “By approaching trans people with the wrong language,” he suggested, “they immediately know that you aren’t equipped to tell their stories.”

As it turns out—and as difficult as it is to admit—those early critics were right. I was taking my first stumbling steps on a long and arduous learning curve. What followed were years of research and self-education on a topic about which I now understand I was appallingly ignorant. The tipoff? I had to look up the word “cisgender.”

But no one else had stepped up to tell the Trinidad story. Stanley Biber had been gone for more than a decade. Marci Bowers had relocated her practice to California. The collective memories of the people who lived that story were fading. I was convinced the story was worth the risk but equally aware that my role as an outsider would never be more harshly scrutinized.

Ultimately, I decided to do what I’ve always done as a journalist: Get out of the way, let the subjects speak for themselves, and allow readers to draw their own conclusions.

Things began to change for me during interviews in Trinidad and in the far-flung locales where Trinidad’s medical pilgrims had settled. As I listened to their stories, I began to question many of my assumptions about gender identity, sexuality, and assigned sex. And I began to understand why 97 percent of those who commit to a difficult surgery that promises no easy solutions would choose to do it again.

During long talks in her Rhode Island apartment, I learned from Biber patient Claudine Griggs how gender, genitalia, and sexuality are interrelated but distinct, and why it’s risky to base gender identification on a quick glance between a newborn’s legs. Over a meal in the Bay Area, I learned from surgeon Marci Bowers how gender identification involves the brain and self-perception, and how debilitating the consequences can be when your gender and your genitalia don’t match.

Gender researchers convinced me there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to gender dysphoria, which is why some affirm their identities in email signatures specifying their preferred pronouns, or by sending social cues through the way they dress, walk, and talk. Others turn to hormone therapy for relief. Still others—those who can afford it and are willing to endure the physical ordeal—find relief through more radical therapy involving hormones and surgery.

Sexual orientation? About three-quarters of transgender men and women identify as homosexual, bisexual, queer, or asexual, but the remaining 23 percent are heterosexual. As Griggs once told me, post-transition individuals “have to accommodate their desires in conjunction with the real-world possibilities. The possible can deform the desired.”

By the time I was done, I was well aware of the high rate of suicide and suicidal thoughts among that population, of insurance companies denying them healthcare coverage, and of athletic programs denying them the right to compete. Some in our society are oppressing a group of people I’ve gotten to know over Thai food, in coffee shops, and during intimate confessional moments. The oppressors’ ideas are rooted in scientific ignorance, stubborn religious fervor, and cultural prejudice.

I, too, was comfortable with my ignorance, flawed assumptions, and biases. But I set out to educate myself, as anyone can, and must, if we’re ever to overcome prejudice. So, I’m the same cisgender male that I was at the start of this book project. What I learned along the way makes it impossible to tolerate the demonization of people who must summon the courage simply to be themselves each day. I accept and support the “nothing about us without us” ethos of storytelling. I understand that my telling of the Trinidad story might have been different had I lived the transgender experience firsthand, so I have told it as a late-blooming ally.

Martin J. Smith, a former senior editor at the Los Angeles Times Magazine, is the author of five novels and five nonfiction books, including the recently released Going to Trinidad: A Doctor, a Colorado Town, and Stories from an Unlikely Gender Crossroads (Bower House).