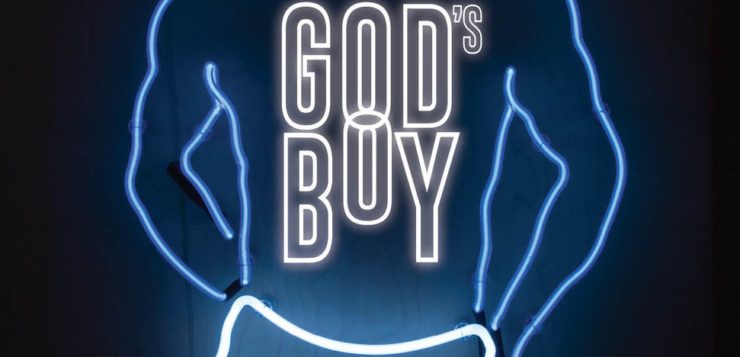

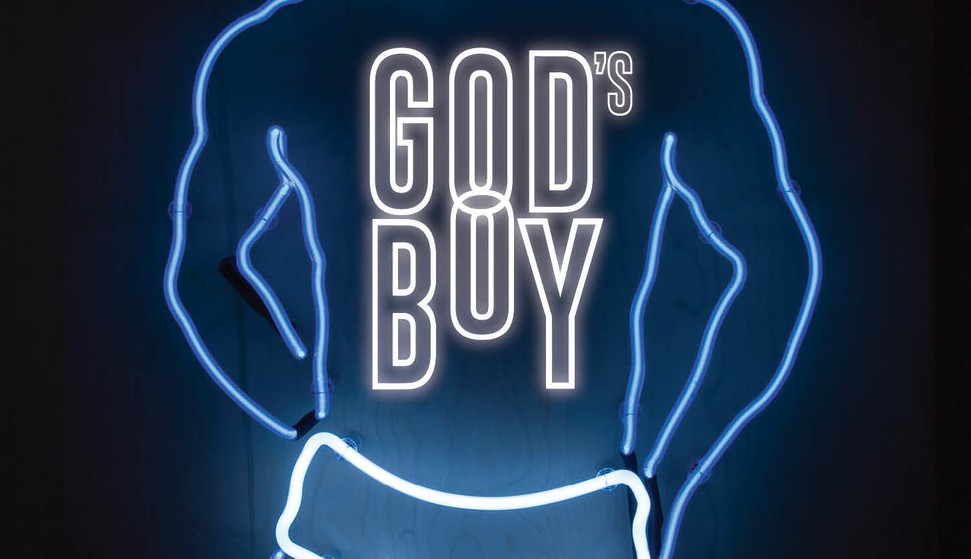

Andrew Hahn’s first chapbook, God’s Boy, published by gay literary press Sibling Rivalry, rattles the cages of his upbringing, which included time as a student at Liberty University, founded by televangelist Jerry Falwell, where he felt culturally marooned. Not merely licking his wounds, Hahn has broken free and revealed the spiritual battleground written across queer bodies wherever God has led mankind into the land of toxic masculinity.

I discussed God’s Boy with Andrew in an email exchange that allowed us to explore the main themes of his poetry, including his complicated relationship with evangelical values and with his God. It was originally published on the Ecotheocollective.

— PK Eriksson

PK Eriksson: I noted a white-hot intensity in the poem “it would have been easier if you died.” It seems that, as gay men, we often do not allow ourselves to feel that kind of unbridled love, or some of us become servants to it, or we sublimate it to drugs or leather or extreme sex. This seems to be more common in gay women and men than their straight counterparts. Can you speak to this experience?

Andrew Hahn: I think there’s this stereotype that gay men “fall in love” quickly, but I think we’re too quick to call it love when I think those feelings are fueled by a specific kind of desire. In my experience, it’s been the desire for someone to want me that drove me into relationships or sex. Many of us have a fear of rejection, a need to be validated—more than straights, because we grow up in environments that reinforce the misbelief that we’re unlovable. We might grow up believing we’ll be disowned, kicked out of the house, homeless, and even killed, and all of these fears are valid.

PK Eriksson: Many of your poems speak to the fear of loving and being loved. Within the context of inter-generational love, do you see balanced love as a possibility?

Andrew Hahn: Oof, that’s a loaded question. In the past I’ve dated men 24 years older and 13 years older, but currently I have been in a relationship with a man 19 years older than me for a year and a half. I have commitment issues. Both of our parents are divorced and remarried. Both of our mothers were addicts. So we bring a lot of baggage to the table. There is a long history of older-younger relationships that serve as a mentor/mentee sort of thing where the older shows the younger the ways of our people. Neil Bartlett’s Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall is a good example of this.

But in my relationship, it’s different. He came out at 39 and I had gone crazy learning as much as I could about our icons, AIDS history, classic movies, etc. Most times I think it’s possible that the older man is young at heart. In my case, my partner sometimes acts much younger than me, and I much older than him, so there’s a balance in that respect. However, economically, the scales often shift. I think there will always be a power dynamic to navigate, but it’s not impossible.

PK Eriksson: Despite the Sturm und Drang that God and his followers impress on the speaker in your poems, he still wants to see romance. Perhaps he seeks it as result of a that spiritual oppression. How do you see high romance serving gay life beyond its presence in poetry?

Andrew Hahn: I’m not particularly interested in seeing queer people conforming to hetero norms in their relationships. We can make them whatever we want them to be. Open relationships work for many couples. And it’s cool for us because open relationships are fairly taboo for straights. I know many gay couples who have the white-picket fence kind of life, but that’s not something I’m particularly interested in.

PK Eriksson: The overwhelming sense of masculinity in God’s Boy almost feels claustrophobic at times. As gay men, we often feel swept into the cult of masculinity. Where might the speakers in these poems get some relief?

Andrew Hahn: Masculinity itself isn’t toxic. It’s being told that boys can’t cry, or that boys should channel our energy into violence, or that boys can’t show sensitivity, etc. that create toxic men. White evangelicalism reinforces the “power” men have over everyone else as some sort of birthright. So, when these men who have been fully consumed by this “power” meet resistance, they believe they’re entitled to do whatever they need to do to get what they want. The speaker meets this resistance in some of the poems.

As far as relief, I think there are moments when the speaker is alone or with a man who pays him attention in sort of a dream state, like the man in “the river: fort lauderdale” or the lover in “the river: lynchburg.” While some of the moments might be painful, I think the speaker feels safe enough to express himself with these men more than he would with dad/dy or even God at times.

PK Eriksson: As a gay man, I have often found great models of masculinity who often go unnoticed or underappreciated, but I mostly felt locked out of them and ended up, at least earlier in my life, in less than less savory company. Do you see anywhere in the culture where to be a man is more balanced?

Andrew Hahn: It’s hard to meet anyone these days. Thankfully social media have helped connect people from around the world, and I’ve been lucky to meet and make friends with some really wonderful guys. In real life, I’m fortunate to have made quality friends from Liberty who have thought hard about the world and where they fit into it, what kinds of people they want to allow into their spaces, etc. But to answer your question, I think it comes down to who men choose to be and somehow finding likeminded people.

PK Eriksson: The poems suggest a personality who has been squashed by God, if not religion. Where do you stand on God after putting out a book like that?

Andrew Hahn: I really appreciate this question! God and I are like old friends who run into each other at the bar or the grocery store. We used to be really close, and I think it’s no surprise that God (not church) used to be my entire world. I’d talk to God on my walks, in the car, on the couch. I’d ask him questions about the people around me. He’d answer, almost always. And then a church asked me to leave, and then God stopped answering. This sounds like some Old Testament story. But I’m not mad at God. I don’t hate him. I think white evangelicals have a very wrong idea of the God that I knew, and I hope they go away forever.