I am not a writer’s writer. I am not talented in that way. I keep my fingers crossed and pray to a higher power to find the correct word in conversation in time to save me from humiliation.

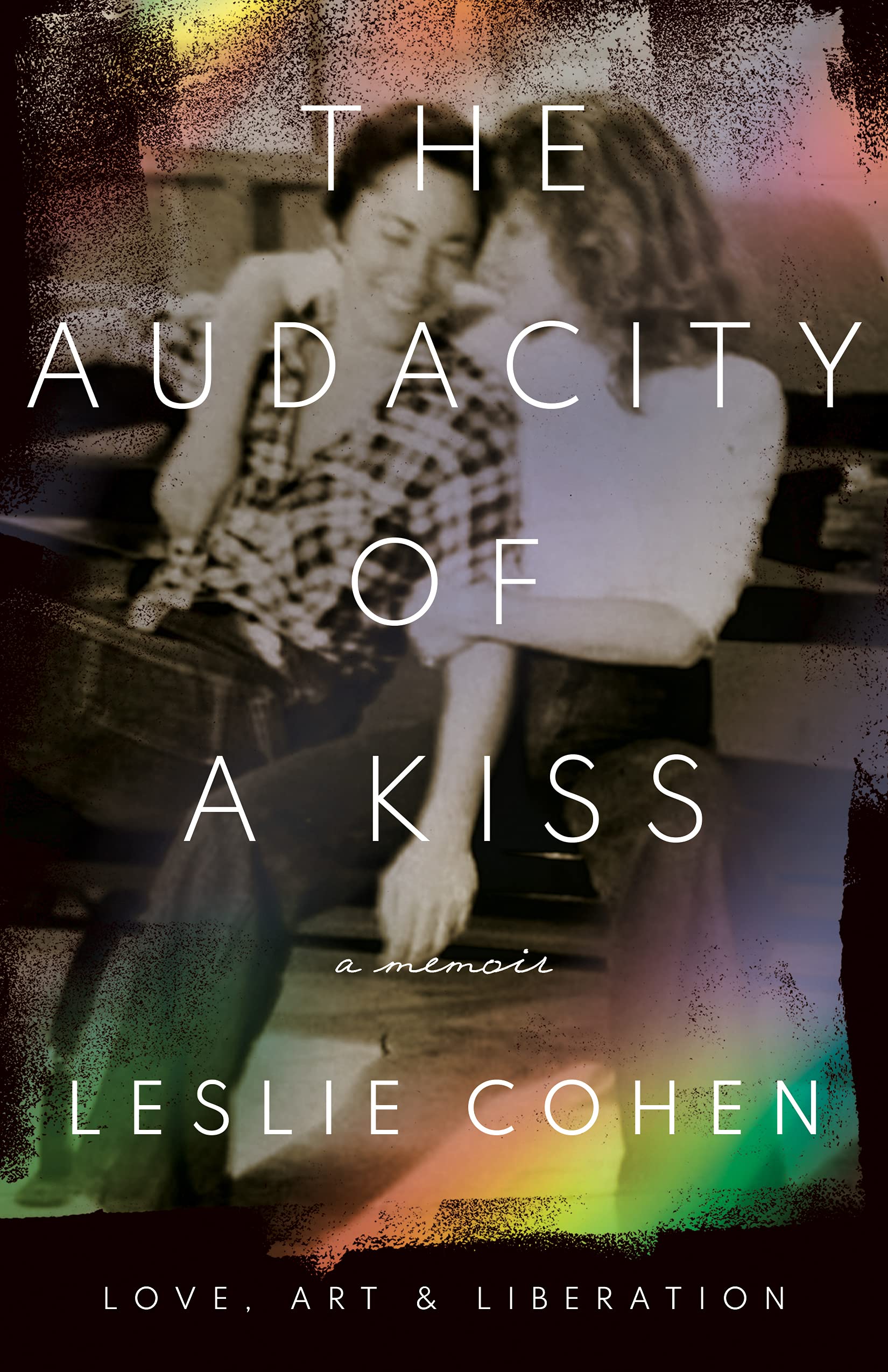

So, you may ask, how did I manage to write a memoir The Audacity of a Kiss (to be published by Rutgers University Press and released in September)? It took ten plus years of on and off again persistence. I was motivated by anger and love. I had two stories that I felt driven to convey because no one else was telling them.

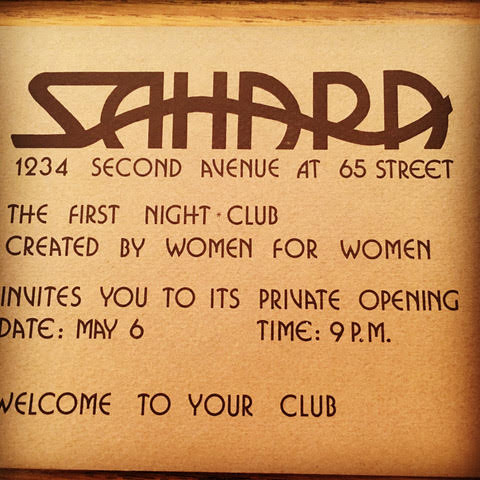

One story needed to be shared because if I did not memorialize it in some fashion, it would be lost to the annals of LGBTQ+ history. I refused to let it die on the vine. My girlfriends Michelle, Linda and Barbara and I had created a groundbreaking women’s club, Sahara, in 1976 and our accomplishments and the club’s significance were being disregarded. It was never mentioned in the 30 years since its founding in any writings on the history of feminism, gay rights or nightclubs of that freewheeling era. I did not take well to being ignored, not in light of my feminist understanding of the historical treatment of women. My motivation, pure and simple, was to record for history’s sake what I and others thought was an important contribution to women and LGBTQ+ history. I realized that if I didn’t write the story no one else would. The only way I could correct what I thought was an injustice was to write a book and hope that someone would publish it.

Sahara represented a milestone along the arduous road to gay and lesbian equality, a turning point between the representation of gay people as perverse and sick to the beginning of acceptance and inclusion. It was all in the timing. Up until 1974 the American Psychiatric Associations’ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) listed homosexuality as a mental illness. This classification was the basis for laws criminalizing queer intimacy. State liquor authorities had an excuse to deny liquor licenses to those wishing to open a gay bar. They would not condone what they considered immoral or sick behavior as defined by mental health experts. Thus, the criminal element, the Mafia, ran the gay clubs by paying off the authorities./ The clubs that existed for women were often dives, seedy and uninspired. But in 1974, under the pressure of lesbian and gay activists, the DSM designation of homosexuality as a mental disorder was removed.

As four young lesbians still in our twenties, we might not have been aware of these political machinations directly, but we had certainly experienced the before and after changes subliminally. We were in the midst of the beginnings of the second wave of feminism and gay rights. It was a ground swell of change and Sahara represented it in all its glory. We were determined to make a difference: to open a women’s club that was elegant, a place where women could feel proud of who they were. It was a combination on our part of naivete and grit.

Sahara was the first club created and owned by women for women. We were free to do whatever we wanted, because for the first time, we held the purse strings. Women before us who fronted the lesbian clubs for their Mafia bosses might have had the best intentions for their clientele, but were undoubtedly hamstrung by the men who controlled them.

When the women entered the club for the first time at our opening in May 1976, their mouths fell open and their eyes filled with tears as we handed them a rose at the door. They were being respected and appreciated in a way that they had never been before. They were being attended to. Impressive large contemporary paintings by women artists, many of whom now hang in the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art—Nancy Spero, Harriet Korman, Louise Fishman, Kate Millett, Harmony Hammond, Mary Beth Edelson and others – hung on the walls over large sectional couches covered in black nubby fabric. Rattan fan chairs were placed in the corners surrounded by palm trees.

Singers performed at out live music night on Thursdays or appeared at our DJ booth to promote their latest records—Pat Benatar, Nona Hendryx, Grace Jones, Patti Smith, Linda Clifford, the Savannah Band, Sylvester and others. Politicians like Bella Abzug, Carol Bellamy and Elaine Noble held fundraisers at Sahara and celebrities came to this lesbian club for the first time to endorse them—Jane Fonda, Tom Hayden, Gilda Radner, Jane Curtin, Warren Beatty, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Ntozake Shange, Rita Mae Brown and Adrienne Rich.

And the women and their friends came in droves. They glowed, they laughed, they loved and they danced to the flashing lights in the disco on the second floor. It was a celebration of freedom and pride in who they were and in their surroundings. I could not let these remarkable moments die in the quicksand of time.

The second story that I was motivated to tell for posterity’s sake was my love affair of forty-four years with my lover and now wife Beth. As fate would have it, Beth and I were the models for the iconic sculpture Gay Liberation by the sculptor George Segal that was commissioned in 1979 to commemorate the tenth year anniversary of the Stonewall riot. After thirteen years it was finally unveiled in June 1992 in Christopher Park in New York City across the street from the Stonewall Inn.

Beth and I had met in 1965 in college when we she was straight and I was straightish, or still too ashamed to confront my lesbianism in a world that considered it perverse. By the time we met again in 1976 ten years had passed. She was still straight but I was now a lesbian on the verge of opening Sahara. We fell madly in love. She left the man she was living with at the time and we have been together ever since. The sculpture and our place in it signified to us our deep love, our struggle and desire for visibility to advance the recognition and acceptance of LGBTQ+ lives, and our appreciation of art.

Beth and I had met in 1965 in college when we she was straight and I was straightish, or still too ashamed to confront my lesbianism in a world that considered it perverse. By the time we met again in 1976 ten years had passed. She was still straight but I was now a lesbian on the verge of opening Sahara. We fell madly in love. She left the man she was living with at the time and we have been together ever since. The sculpture and our place in it signified to us our deep love, our struggle and desire for visibility to advance the recognition and acceptance of LGBTQ+ lives, and our appreciation of art.

Since the sculpture has been seen by thousands it seemed appropriate that those who stood before it, especially those suffering from confusion or despair about their identity or sexuality know our love story. The two women sitting on a park bench cast in bronze and painted white, are still very much in love. The love between women or men of the same sex is a gift, not an anomaly. Our love for each other is our blessing. I wanted people to know that, to inspire them to love unashamedly.

Leslie Cohen has been a museum curator, a nightclub owner and promoter, a limousine driver, and a lawyer, as well as a writer whose work has appeared in such publications as Curve and The New York Times Style Magazine. Leslie was the co-owner of the groundbreaking women’s nightclub Sahara. Now retired, she and Beth live in Miami, Florida with their cat, Birdie.

Leslie Cohen has been a museum curator, a nightclub owner and promoter, a limousine driver, and a lawyer, as well as a writer whose work has appeared in such publications as Curve and The New York Times Style Magazine. Leslie was the co-owner of the groundbreaking women’s nightclub Sahara. Now retired, she and Beth live in Miami, Florida with their cat, Birdie.

Leslie Cohen’s memoir The Audacity of a Kiss, featuring stories of how she helped found the Sahara club and other contributions and struggles in the fight for feminist and queer liberation, comes out in September.

Discussion3 Comments

What a beautiful story! Can’t wait to read the book. Thank you Leslie.

A great article that brings back memories of those years. BTW, Segal’s sculpture wasn’t really unveiled in 1992 in Christopher Park. It was merely relocated to that location after standing for years in Orton Park, a lovely neighborhood park in Madison WI. We were sorry to see it leave when NYC finally matured enough to follow our lead!

Leslie I admire you a lot you for what you did .in the 1970s to start a club for lesbians must have been so difficult but you did it and gave lgbt people a place where they could belong .not feeling less than anybody ,a place they could feel good about themselves.you are my hero . Thank you Leslie for your bravery and courage.