Learning to Trust: Australian Responses to AIDS

Learning to Trust: Australian Responses to AIDS

by Paul Sendziuk

University of New South Wales Press, 262 pages

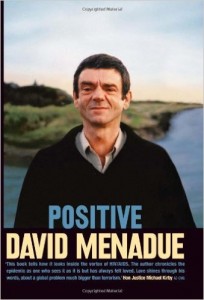

Positive

Positive

by David Menadue

Allen and Unwin, 243 pages

WHEN WE TALK about the history and future of AIDS, we tend to do so through narratives of tragedy and disaster and despair. The reasons for this are obvious. But, except within the academic and the professional journals, we rarely acknowledge that there is another side to the story—one of hope and achievement. In Learning to Trust, Paul Sendziuk offers us access to this other story—not through fiction or journalism, as might be expected, but through history: the history of Australia’s remarkable success in containing the spread of HIV/AIDS.

The first cases in Australia of what would come to be called AIDS were transmitted in 1981. Three years later, there were 2,500 new infections. But then a surprising thing happened. Infection rates dropped; and they kept on dropping. In 1988 there were 750 infections. In 1992 there were 500, an annual rate that has been maintained ever since. How did Australia manage to reduce its rate of HIV infection faster than any comparable country—and, in so doing, save the lives of thousands of people, both gay and straight, and avoid the social and political backlash against gay rights that this most political of diseases (as Dennis Altman has called it) threatened to bring with it?

Sendziuk starts by pointing to the existence of two approaches to public health management. One emphasized the role of the individual—seen as “irresponsible and dangerous”—who had to be coerced and controlled by the state and the medical profession. The other saw the communities in which people lived, and recognized these as necessary partners in the creation and delivery of the behavioral change that, in the end, was the only possible basis for successful health policy (or saving lives, as we might put it). State, profession, and community each had expertise and resources that the others needed and it was only by working together and trusting each other that anything at all could be achieved. This meant that government agencies relied on the gay community to educate itself, providing funding for safe sex materials that spoke to the real experience of gay men. Avoiding the clinical language of the medicos and the politeness of public discourse, “an arse was an arse and a fuck was a fuck,” as one activist put it. And the images! As Sendziuk’s illustrations make clear, this stuff was not designed for public consumption.

When gay men spoke to gay men and told them what they needed to do to save their lives, it worked. When they did so with millions of dollars of government funding, they saved even more lives. And if the government could stand at arm’s length, denying all responsibility for content, then the truth could be told in an unvarnished form without public controversy and at very little political cost.

When we realized how well this approach had worked among gay men, it seemed obvious that it would be applicable to other risk groups. When it came to junkies and prostitutes, the message was what it has been with gay men: Is this activity illegal? immoral? Not our problem; here’s what to do to save your life. Needle-exchanges, sex-worker resource centers, community magazines all spread the word on safe injecting and safe fucking. Sex workers and drug users did change their behavior. They just needed to be told how by people they trusted. This explains the second surprising fact about the AIDS epidemic in Australia: it never really spread much beyond gay men.

But if, in adopting the community participation model, Australia took up the high road to success, the question remains, how did we come to choose this rather than the other road? It is not that hard when talking about AIDS to avoid whiggish notions of progress—the example of the United States and the Netherlands, for example, gives us too stark a picture of just how badly it went in some cases. But Sendziuk is meticulous in picking his way though the complexities and realities of Australian public life. Learning to Trust is not a manual for AIDS policy that can be applied to all circumstances, but it is a reminder that there is always hope and that ordinary people can do extraordinary things by working together.

David Menadue takes us on a very different journey through the same territory in Positive, his memoir of living for twenty years as an HIV-positive gay man. Menadue is a political activist, one of the leaders of the people living with HIV/AIDS movement in Australia and, before that, a gay rights activist. He brings to this story both personal and political insight. It is a story of courage and fear, of bad behavior and remarkable sacrifices, of the importance of family and work and friendship, and the value of positive thinking and acting.

Sometimes his story is clear and frank: the problems of coming out to family and friends and workmates; the difficult politics of the AIDS organizations as they struggled to find ways forward, always half in the dark. Sometimes it is the passing reference that grabs you: the arrival of AZT in 1988, reminding us of the time before that when there were no therapeutic drugs at all; the time he came out as HIV-positive to a workmate and found that she had already been reading about the disease and seemed well-informed. Positive is not a highly literary memoir. Menadue tells his story with a spare, straightforward prose, which I think makes it all the more powerful. Here we have one of the very large number of ordinary people whose lives were transformed by their encounter with an extraordinary disease—and who, in Menadue’s case, set out deal with it, and then to tell us about it.

Graham Willett is the author of Living Out Loud: A History of Gay and Lesbian Activism in Australia.