FOR MUCH OF HIS LIFE at home, Rajiv Mohabir was the only one in his family who seemed interested in the songs and stories told by his grandmother, Aji. Mohabir’s father, who “would rather have silence than Sanskrit, hell than Hindi,” enforced on the family a rejection of their Indo-Guyanese past, its language, and its religion in an attempt to assimilate into the dominant culture after they moved to North America, first to Florida and then to Toronto.

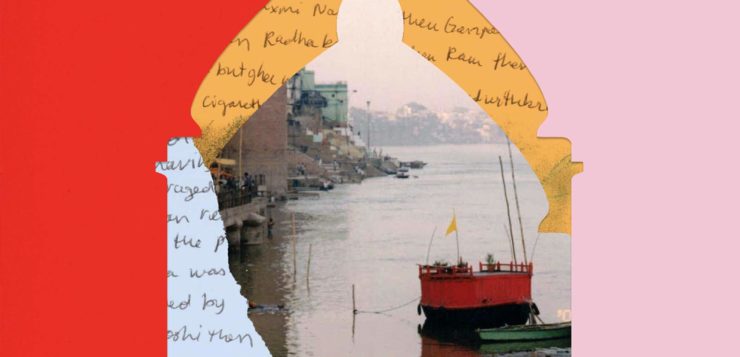

Fascinated by the past, Rajiv goes in search of his heritage, embracing it, learning as much as he can from Aji, recording and translating her native Creole Bhojpuri into English. While studying at the University of Florida, he attends South Asian Language Summer Institute at University of Wisconsin, then spends a year in Varanasi, India, improving his language skills, collecting songs, and visiting what might be his family’s ancestral home.

Upon returning to the United States and finishing college, Mohabir is accepted into the New York City Teaching Fellows Program to teach English as a Second Language to K-12 students. Among other “brown queers” from the West Indies and South Asia in multicultural Queens, he begins to discover community, enters and exits a controlling relationship with another Guyanese man, and starts to find his voice as a poet. After experiences that lead him to question his writing talent at the Voices of Our Nations Art Foundation’s annual workshop in San Francisco, Mohabir returns to New York to discover that he has been accepted into the MFA program at Queens College.

Unfortunately, after an innocent visit from a gay male friend, he is outed by a cousin as an “antiman” or “Auntie Man,” a Caribbean slur for gay men, which causes further distance between Mohabir and his immediate family and a complete break with his aunts, uncles, and cousins: “I would live in Queens and Aji would die and family would gather from all over the world to keep wake but no one would call me even though I would live only one subway stop west. I would have to wear the name antiman as scales, never able to molt it when it no longer fit my body. But this would also mean that I would be a dragon with wings and a tongue of flame. I would have to get used to flying.”

Recipient of the Prize for New Immigrant Writing from Restless Books, Antiman overflows with languages—English, Bhojpuri, and Creole—and with various forms of storytelling, including prose and poetry, journal entries, “fauxtales,” transcriptions of recordings of his grandmother, definitions, and “misreadings.” This multiplicity of genres enriches the book and allows the reader to experience the various worlds Mohabir inhabits.

Currently an associate professor of poetry in the MFA program at Emerson College, Rajiv Mohabir’s first book, The Taxidermist’s Cut, was a finalist for the 2017 Lambda Literary Award in Gay Poetry; his second, The Cowherd’s Son, won the 2015 Kundiman Prize. Not quite a coming out story, Antiman is an illuminating “hybrid memoir,” a record of Mohabir’s coming to terms with himself, discovering who he is, and his embrace of multiple communities and cultures. As he writes: “Diaspora is a queer country/ How can you be at once two species from two places?”

____________________________________________________

Reginald Harris, a writer and poet based in Brooklyn, is the author of 10 Tongues (2003) and Autogeography (2013).