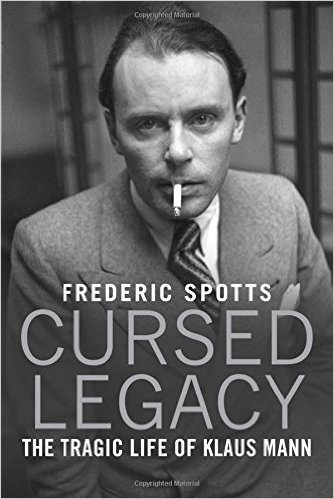

Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann

Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann

by Frederic Spotts

Yale U. Press. 330 pages, $40.

KLAUS MANN was born in Munich in 1906. Like all of his five siblings, he was a precocious child who would grow into an even more talented adult, which is not to say that his talents would be widely acknowledged during his lifetime. Coming from a family whose head was the world-renowned author Thomas Mann should have given him a leg up, but it did not. In fact, Thomas went out of his way to stifle Klaus’ talents in the most denigrating, hurtful ways possible. It was as though Thomas saw in Klaus not a son who had inherited his own creativity but a rival who might overtake him as a writer one day.

The Mann household was not a loving place where the children’s talents were encouraged and nurtured. Quite the contrary, it was a locus terribilis where the children were lucky if they were completely ignored, as was the case with Klaus’ brother Michael. If they were unlucky, as was Klaus, they would constantly bear the brunt of Thomas’ mockery and ridicule. Except for Erika, who was Thomas’ favorite, none of the Mann children escaped his overbearing personality and wrath. In Klaus’ case, the abuse went beyond verbal belittling. Not only did Thomas time and again dismiss both Klaus and his work as meaningless, he also went out of his way to undermine Klaus’ literary endeavors and even denied him credit on a volume that the two men co-edited.

Against this backdrop, Frederic Spotts chronicles the life of Klaus Mann in his aptly titled book, Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann. Delving into numerous aspects of Klaus’ life—his relationships with family members, his friends and acquaintances in the art world, his search for love and his homosexuality, his heart-wrenching efforts to fit in, his drug abuse and death wishes, and his voracious need to read and write—Spotts offers a keen insight into the struggles of a young man who wanted nothing more than to make a name for himself in the literary world.

Against this backdrop, Frederic Spotts chronicles the life of Klaus Mann in his aptly titled book, Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann. Delving into numerous aspects of Klaus’ life—his relationships with family members, his friends and acquaintances in the art world, his search for love and his homosexuality, his heart-wrenching efforts to fit in, his drug abuse and death wishes, and his voracious need to read and write—Spotts offers a keen insight into the struggles of a young man who wanted nothing more than to make a name for himself in the literary world.

Spotts divides Klaus’ life into periods that start with his formative years, 1906 to 1924, and end with his death in 1949. Starting in 1933 and the Nazis’ rise to power, Spotts breaks the remainder of his book into chapters that cover single years. He gives each of the chapters a title, most of which are helpful, but some miss the mark by a wide margin. Chapter 3, for example, which is titled “First Drugs” and covers the years 1929-1932, includes a few passing references to drug use, but it’s in a chapter called “Homosexualities” that Klaus’ drug addiction is explored in detail.

Elsewhere, Spotts delves deeply into the homosexual aspect of Klaus’ life and does a superb job in covering Klaus’ casual flings as well as his deeper love affairs. In each instance, Klaus is presented as looking for love but never quite finding a healthy, long-term relationship. He is seen as a lonely, restless soul who cannot keep to one person any more than he can stay in one place. Unlike his father, who hid his homosexuality from the world, Klaus was very open about his sexual orientation. At age nineteen he produced the first openly gay novel in Germany, Der Fromme Tanz (“The Pious Dance,” 1926). A year earlier he and his sister Erika had presented the first play about a lesbian relationship, Anjou und Edith. Thomas, embarrassed as always by Klaus, reacted by publishing an essay titled “Über die Ehe” (“On Marriage”) in which he condemned homosexuality.

From as early as age five, Klaus yearned to put his thoughts to paper. Unable to write, he dictated his ideas to Erika, who was two years his senior. Throughout his life, he would be a voracious reader and a frenetic writer. At thirteen, already aware of the dysfunctional dynamics of his family, he wrote a tale about a young man who, mistreated by his brother and abandoned by his parents, would eventually succumb to drugs and die of an overdose. Later, he wrote a comedy for his mother that Thomas dismissed as a tactless piece of juvenilia. Despite his father’s constant attempts to undermine his work and his own lack of self-confidence, Klaus had 31 essays and critical reviews to his name by the age of nineteen. He would later go on to produce numerous novels, essays, newspaper and journal articles, stage productions, and even a screenplay.

The project that had the most immediate impact was Klaus Mann’s anti-Nazi journal, Die Sammlung (“The Collection”), which featured essays, poems, and other genres from over 300 writers from various countries. Thomas, under pressure from his German publisher, Gottfried Bermann, denounced the journal publicly to prevent his own works from being banned in Germany. Klaus’ 1936 novel Mephisto: Roman einer Karrier (“Mephisto: Novel of a Career”), his thinly disguised exposé on Gustaf Gründgens’ collaboration with the Nazis, was finished in 1936 but would not be published in Germany until 1981, 33 years after his death. Once it hit the stands, it became an overnight success, selling close to a million copies, and it was later adapted for both stage and screen.

Klaus gave a speech in 1930 titled “What Kind of Future Do We Want?” With its publication, he became one of the earliest and most vocal opponents of Nazism. From this time onward, his writings took on an increasingly political bent, which was encouraged by his uncle, Heinrich Mann, who was himself an outspoken activist against the Nazis. Klaus’ novel Flucht in den Norden (“Flight North,” 1934) would become the first anti-Nazi exile novel. (By now Klaus was living in Paris.) It would also prompt the Nazis to start a dossier on Klaus and, in 1934, to strip him of his German citizenship. Both he and Heinrich would join the ranks of those authors who were blacklisted in Germany and whose books were burned by the Nazis. Thomas, for his part, remained quiet, not wanting his holdings in Germany to be confiscated or the German book market to be shut off.

Interwoven with Klaus’ activism and literary career were his battles with depression and his recurring longing for death. In investigating the genesis of these psychological issues, Spotts attributes Klaus’ depression not only to the abusive environment of the Mann household but also to a possible genetic proclivity, given that several members of the Mann family had committed suicide. He traces Klaus’ obsession with death back to a near-death experience with appendicitis as a child. While Klaus’ preoccupation with death is well documented in both his writings and his diaries, Spotts notes that Klaus viewed death not only as an escape from a life of misery, but also as a refuge, a place of peace and quiet. While it has generally been assumed that Klaus committed suicide on May 21, 1949, Spotts questions this interpretation, noting that Klaus did not behave like a man about to take his own life. He had just completed an inventory of all his work from 1939 to 1948, outlined a plan for the next ten years, signed a contract with Langenscheidt to publish a German version of Mephisto, and been welcomed back to Germany with positive reviews of his works in the German magazine Der Spiegel. The circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery to this day.

In Cursed Legacy, Spotts does an impressive job of capturing Klaus’ legacy as a novelist, essayist, editor, playwright, journalist, political activist, gay rights activist, war correspondent, and American soldier. He also offers considerable insight into the emotions, the suffering, and the dreams of this multi-faceted individual. While he gained some renown for his accomplishments during his lifetime, most of this recognition came posthumously. Thus Klaus would never know that he had finally succeeded in stepping out from under his father’s shadow and into the light of day.

Stephanie E. Libbon is an associate professor of German at Kent State University.