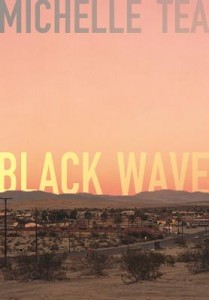

Black Wave

Black Wave

by Michelle Tea

The Feminist Press at CUNY

320 pages, $18.95

MICHELLE TEA’S new novel—for lack of a more precise label—is a work of meta-fiction, a narrative about a writer trying to write while also trying to survive the 1990s, when the world was expected to end with the millennium. Michelle, the narrator, introduces the reader to gentrification in San Francisco, and the search for hangouts where the non-genteel (the young, the poor, the queer) are still welcome: “Michelle wasn’t sure when everyone started hanging out at the Albion. She had managed to pass the corner dive for years without going inside, simply noting the dank, flat-beer stink wafting from its open doors, catching the glow of the neon sign hung above the bar—service for the sick—in hot, red loops.”

The first half of Black Wave describes a kind of “lost weekend” that lasts for months, in which the 27-year-old narrator is rarely sober, often high, and usually “in love” with someone much younger than she is, or not available for long. She loses the emotional support of a responsible woman who cares for her but draws the line at Michelle’s use of heroin with a teenage girl. Michelle adores her friends but lets them down. She barely earns a living by working in a bookstore, and she spends every weekend in pursuit of ecstasy and inspiration.

This narrator is lucky enough to have an affordable place to live, a crumbling house owned by a “sad widower” who rents rooms to young lesbian artists. One of them, Ekundayo, seems hostile and aloof; at Michelle’s going-away party, she glares “at the little doped-up fools snorting lines off the dumpstered coffee table.” Addiction in general has been a huge problem in queer communities for generations, and Ekundayo’s cameo role suggests an alternative way of surviving in her own milieu: being logical, clear-eyed, and stone-cold-sober.

Michelle is afraid of becoming too dependent on substances she considers dangerous, but her decision to move to Los Angeles is not really based on a desire to get “clean.” She moves for several reasons: her gay brother lives in L.A., and it is the home of Hollywood, where she hopes to find success as a screenwriter. She lucks into another job at an independent bookstore, a type of business that is already (in the ’90s) threatened with extinction. She drinks alone every weekend while trying to write about a “universal” character who doesn’t exist.

Michelle is afraid of becoming too dependent on substances she considers dangerous, but her decision to move to Los Angeles is not really based on a desire to get “clean.” She moves for several reasons: her gay brother lives in L.A., and it is the home of Hollywood, where she hopes to find success as a screenwriter. She lucks into another job at an independent bookstore, a type of business that is already (in the ’90s) threatened with extinction. She drinks alone every weekend while trying to write about a “universal” character who doesn’t exist.

Michelle’s new urban setting is described as dream-like and movie-like. The natural environment she travels through between San Francisco and L.A. seems alarmingly apocalyptic; California is shown as a former paradise stricken by drought and pollution. After she arrives at her destination, she learns that the world really is coming to an end. Communication and transportation systems are shutting down, and individuals are going back to communicating one-to-one, even as they lose contact with everyone they know outside their own neighborhoods.

In the lead-up to the apocalypse, everyone in Michelle’s environment seems to be having lucid dreams about their soul-mates, who usually live in other parts of the world. In some cases, the soul-mates travel to meet each other. In a long, beautifully written dream sequence, Michelle floats in pristine water with her soul-mate, a brilliant and androgynous teenager who gives her an ultimatum. Michelle loses the dream lover, as she has lost real ones, but she compensates by having regular sex in the bookstore with Matt Damon, one of her Hollywood idols.

The narrative focus on Michelle’s unrealistic search for happiness gives this book a flavor of adolescent self-obsession. However, much of it can be read as a parody of more earnest dystopian and utopian fiction about approaching doom and miraculous redemption, and the social satire is often hilarious. The more realistic flashback scenes of Michelle’s childhood in a gritty Massachusetts town with her lesbian mother Wendy and her depressed partner Kym are poignant and believable. This material will be familiar to readers who have read Tea’s previous memoirs, which have gained her a certain cult following. While fantasy and reality are hard to separate in this author’s work, her distinct take on the Zeitgeist of her lifetime is unmistakable.

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.