OUTRAGES

OUTRAGES

Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love

by Naomi Wolf

Chelsea Green Publishing

364 pages, $19.95

OUTRAGES BEGINS in the rare book room of the Morgan Library in New York, where Naomi Wolf has gone to read the manuscript of an unpublished poem that Victorian critic John Addington Symonds wrote at Oxford after falling in love with a classmate—though you might also say that the book began the day Wolf was still a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford and was handed two volumes of Symonds’ letters by her advisor with the words: “You should read these.” Read them she did, and now, years after publishing such bestsellers as The Beauty Myth and Vagina, Wolf has returned to her doctoral thesis.

Although it has been considerably expanded to cover the history of English law on the subject of pornography, sodomy, divorce, the age of consent (which was, incredibly, ten until 1885), Outrages is still about John Addington Symonds—including the correspondence he carried on with Walt Whitman for over two decades. But it’s also about 19th-century England’s attempt to police sex, which takes us into the subjects of cholera, sewage systems, feminism, sodomy, pornography, child prostitution, censorship, cross-dressing, the arrest of the artist Simeon Solomon in a public toilet, Whitman’s reputation among writers like Algernon Swinburne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and what Wolf believes were the first stirrings of England’s movement for homosexual rights. Many people think that movement began with the trials of Oscar Wilde, but Wolf argues that it can be traced back to two pamphlets by Symonds: A Problem in Greek Ethics and A Problem in Modern Ethics. The latter inspired Henry James, of all people, to call Symonds one of “the great reformers,” “the Gladstone of the affair,” the affair being the campaign for homosexual legal rights.

By the time Symonds moved to Davos, he had already been involved in two homosexual scandals. The first dates back to his time at Harrow, when a classmate confessed to Symonds that he was having an affair with its headmaster. After matriculating at Oxford, Symonds was out walking with a teacher one day when he mentioned his friend’s confession, upon which his teacher advised Symonds to tell his father, which he did. Dr. Symonds promptly informed the headmaster that if he did not resign he would expose him as a pederast; and even after the headmaster did give up his post, Dr. Symonds hounded him with the same threat every place he went—precisely the sort of blackmail that kept homosexuals on edge in Victorian England. Later, when Symonds himself was teaching at Oxford, a student accused him of a sexual infatuation with a classmate, and although Symonds was allowed to remain after his private life was investigated by the faculty, the cloud on his reputation never really lifted.

Nothing is dumber than feeling superior to previous eras because of the beliefs they held—our era is of course full of its own idiocies that future generations will mock—but the England in which Symonds lived from 1840 to 1893 was the most peculiar amalgam of romantic ideals of male friendship and an almost hysterical aversion to homosexuality. As Wolf points out, it was a country in which men could walk arm in arm in public, sleep in the same bed, bathe naked together in rivers, and fall in love with classmates at Oxford and Cambridge, a fate made famous by Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., the elegy he wrote after his best friend died at 22, and a perfect example of this ethos. Although the brutal manner in which upper classmen used younger students for sex at Harrow appalled Symonds, at Oxford relationships were far more soulful, which is why Wolf went to the Morgan Library to read In Memoriam Arcadie, which Symonds wrote not because his beloved had died but because Symonds had decided there was no future for the two of them in Victorian England.

England’s law ordering the death penalty for sodomites goes back to 1535, and while executions ceased in 1835 (for reasons not explained in this book) when the law came up for reform in 1857, the move to reduce the punishment to “maritime transportation” (send them to Australia) or penal servitude (hard labor) was vehemently rejected by the House of Lords. Sodomy, they declared, was so heinous that society’s revulsion could only be expressed with capital punishment. It remained a crime so awful that Dr. Symonds could threaten the headmaster of Harrow every time he assumed a new post, a persecution that the young Symonds had unwittingly set in motion.

One can only imagine the effect of what Dr. Symonds did to the headmaster had on his teenage son, since, as the father suspected, Symonds had already begun wrestling with the issue that would torment him for much of his adult life: his attraction to other men. Symonds, on the advice of his father, got married, had children, and eventually moved abroad, where he wrote a history of the Renaissance, translated Cellini’s writings, and wrote a biography of Michelangelo while suppressing his own “sodomy poems” and choosing to show A Problem in Greek Ethics and A Problem in Modern Ethics only to friends.

The problem with teaching the classics in Victorian England was that when reading Platonic dialogues like The Symposium or Phaedrus it was obvious that same-sex desire was not only taken for granted but honored by the ancient Athenians. The problem in modern ethics was that Victorian England—whose educators often bowdlerized the ancient texts, expunging all references to pederasty—regarded homosexuality with such fear and loathing that when Symonds published an anthology of Greek poetry, one of his reviewers, the Reverend Richard St. John Tyrwhitt, singled out Symonds’ reflections on the beauty of a young Greek athlete (a passage that we know Oscar Wilde read because he annotated it in his copy) as “English decadence.” In praising the ancient Greeks, Tyrwhitt claimed, Symonds was calling for “the total denial of any moral restraint on any human impulses” and thereby rejecting Christianity, the sense of sin, and decency in general. Even Symonds’ acknowledgment that he had been influenced by Walt Whitman, “whatever on earth Mr. Symonds means by it,” was alarming, because people of course knew quite well what he meant.

Indeed, what Whitman meant to Symonds is the chief thread of Outrages. The two of them could not have been more different. Symonds was frail, married, and forced to circulate his homoerotic poems among friends, one of whom, alarmed by the increasingly strict laws on obscenity in England, begged him not to send them because merely being the recipient of such things could get you arrested. Whitman, on the other hand, the unmarried flâneur with the open shirt, had published poems in Leaves of Grass (1855) that celebrated the manly love of comrades in terms so clear that Whitman became an inspiration for Symonds in his drive to repudiate Victorian persecution. When Symonds published his poems, he changed the genders, a hypocrisy that led him to reflect: “I am become a real Penelope of literature—weaving subtle embroideries of verse and then unraveling what I weave.” When one friend did ask about his poetry, Symonds wrote back: “Poems—? Verses? Des Vers? Yes, worms—a wormy writhing putrescent entanglement of low animal lives bred in the decaying depths of my gangrened Soul. Lots of them—some 2000 lines—2000 wriggling loathsome worms [which]I hate, the evil birth of wasted hours; forgotten now and abandoned with wringing hands and my Soul crying ah, ah! To little purpose.”

For more than two decades, Symonds wrote letters to Walt Whitman trying to get the author of “Calamus” to openly declare himself to be what Symonds could not. England was so far ahead of the U.S. in the 19th century in dealing with other issues of modern life that it may seem odd to realize that it was Whitman whom Symonds and Wilde regarded as the avant-garde on this one. But it was Whitman whom Wilde wanted to meet above all others when he toured the U.S., and when Wilde went to Camden, New Jersey, he not only seized the opportunity to tell Whitman what his work meant to him but boasted to friends afterwards that he still had Whitman’s kiss on his lips. Whitman was a beacon for Symonds and Wilde, even though—despite Symonds’s persistence—he refused to admit that he was “that way.”

“That the calamus part,” Whitman wrote in reply to an August 3, 1890, letter in which Symonds asked the poet in effect to come out, “has even allow’d the possibility of such construction as mentioned for such gratuitous and quite at the time entirely undream’d & unreck’d possibility of morbid inferences” horrified him. And then he really lowered the boom: “Tho’ always unmarried I have had six children—two are dead—One living southern grandchild, fine boy, who writes to me occasionally. Circumstances connected with their benefit and fortune have separated me from intimate relations.”

It was Symonds who actually fathered four daughters; of Whitman’s offspring there is no record whatsoever. But Whitman, despite “Calamus,” was not about to go where the British writers wanted him to; that would have been fatal to his image as the Good Grey Poet, the memorialist of Lincoln and the Civil War. Whitman was constantly refining his public persona: The contents of Leaves of Grass were revised and recalibrated over the course of his lifetime to appeal to as wide a readership as he could get. Each time a different publisher brought out a new edition of Leaves of Grass, not only did the typeface, cover, and likeness of the author change, but so did the contents. Sometimes it was more homoerotic, sometimes less.

To be fair, things were hardly better in the U.S. Whitman was fired from his government job after a copy of Leaves of Grass was discovered in his desk, and the Comstock Law made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious” materials like Leaves of Grass through the mail. In England, the persecution was even more draconian. By 1870, English courts were hearing testimony from doctors called venerologists to determine the guilt or innocence of men picked up for soliciting or having sex with one another by using something called a “sphincterometer” “to assess the anus of the accused. … If there was an opening of ‘4 to 5 cm in diameter,’ then the man under investigation was deemed guilty.” As for the tops, the courts relied on the treatise of a French physician who claimed that men who practiced active sodomy had penises that were correspondingly altered in shape; either a “slim, attenuated member” or a glans tapered like “the snout of certain animals.”

Wolf makes a connection between the increasing censorship and policing of sodomy with other fears of infection that prevailed in early 19th-century England, when there were still open sewers in London, people’s basements contained a cesspit into which their feces were deposited, and cholera and typhus were an ever-present danger. The resolve to clean up the sewers expanded to include a desire to clean up other things, like prostitution and sexual deviance. Flash forward to Oscar Wilde’s trial in 1895 for “gross indecency,” when one of the chambermaids in the hotel in which he’d stayed reported that there were “fecal stains” on the sheets.

Wilde, of course, haunts the story of John Addington Symonds, who died in 1893, two years before Wilde went to jail. Reading Outrages one feels, bubbling up beneath the grim and punitive homophobia that suffocated Symonds, the sublime mockery that turned the Reverend Tyrwhitt into the divinely demented Lady Bracknell—a mockery on which the patriarchy would take its revenge with the three trials of her creator. Wilde was broken by the penal servitude he endured from 1896 to 1897; he died in 1900, not long after his release, after leaving, in The Ballad of Reading Gaol and De Profundis, vivid testimony to the hard labor and isolation that he endured.

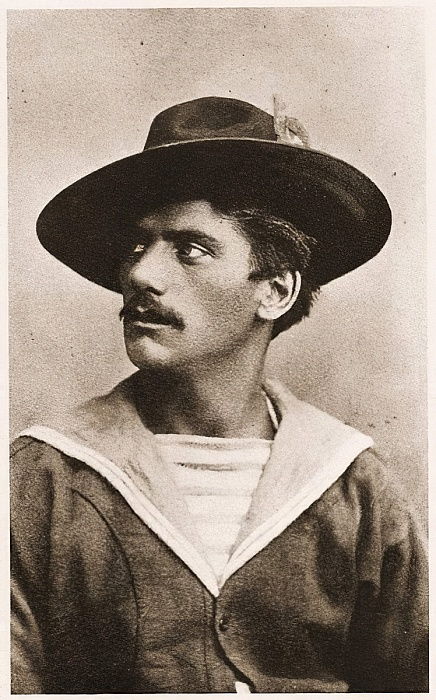

Outrages ends not with Wilde’s demise but with Wolf’s perusal of another work that Symonds suppressed: the memoirs he left to the guardianship of a friend after his death, which were locked up in the London Library and not published in book form until 2017 (by Palgrave Macmillan). In brief, fascinating entries, Symonds describes his piggish classmates at Harrow and the first time he laid eyes on Angelo Fusato, the gondolier he met in Venice, who became part of his family. The memoirs are written in the same clear, straightforward prose that J. R. Ackerley was to use years later in his classic My Father and Myself, and they are about the same struggle: the search for a “masculine” object of affection. “Morally and intellectually,” Symonds wrote, “in character and taste and habits, I am more masculine than many men I know who adore women. I have no feminine feelings for males who rouse my desires. The anomaly of my position is that I admire the physical beauty of men more than women, derive more pleasure from their contact and society, and am stirred to sexual sensations exclusively by persons of the male sex.”

The paradox of Symonds’ life is that, although homosexuality caused him so much personal anguish, he somehow managed to live a life full of relationships and human warmth. After the Reverend Tyrwhitt’s review, which he felt had cost him a professorship at Oxford, Symonds moved abroad with his family, ostensibly for his health, to Switzerland—and met, on a trip to Venice, the handsome gondolier. The irony is that Symonds was cared for by Angelo during his final illness, while Whitman was looked after by a woman in exchange for living rent-free in his house, downstairs. At the time of his death, Symonds was collaborating with Havelock Ellis in an attempt to make sure his upcoming book on sexuality reflected Symonds’ conviction that there was nothing unnatural or heinous whatsoever about homosexual desire.

Outrages was published in England in 2018, and during an interview on the BBC, the moderator, another Victorian scholar, pointed out to Wolf that the phrase “death recorded,” which Wolf had taken to mean execution for sodomy, did not mean that at all; it meant that there was no execution (an Alice-in-Wonderland paradox that is not explained). This was picked up by the media as the sort of “gotcha” moment that people find dramatic. Virago Press pulled the book until revisions could be made, and Houghton Mifflin canceled publication in the U.S. Now it’s being published here by Chelsea Green, and the same BBC interviewer is criticizing her interpretation of the “death recorded” sentence again, this time, in the case of one offender, for confusing male-male sex with the attempt to have sex with children and animals (another definition of sodomy). Wolf’s defense as reported in The Guardian is that her larger point is still valid: such sentences were part of the atmosphere that made Symonds so afraid to publish and come out.

Of course, historical facts matter, but none of these criticisms invalidates Wolf’s book, it seems to me. The mostly young men who were spared execution for soliciting sex with one another were still sent to prison and hard labor, in some cases for ten or fifteen years. (Hard labor could run the gamut from walking on treadmills in total isolation to unraveling ropes used in shipping to working in quarries or dragging vessels in dry dock, all the while being forbidden to speak to your fellow prisoners.) The confusion over one phrase does not invalidate the richness of the research in Wolf’s book. What British law did to homosexuals in the Victorian and Edwardian eras warrants the title of this fascinating study.

Andrew Holleran is the author of the novels Dancer from the Dance, Nights in Aruba, The Beauty of Men, and Grief.

Discussion1 Comment

Naomi Wolf is simply an amazing woman, who has an incredible way of being exponentially wrong about things.