FRANCES BINGHAM has written a biography that reads like an Iris Murdoch novel, specifically A Fairly Honourable Defeat. It’s a moving portrait of the life of British poet Valentine Ackland (1906–1969), but it’s also about her longtime companion Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893–1978), an accomplished novelist and poet. Both writers have gone out of fashion, and Ackland is often difficult to admire, but they both led rather fascinating lives. (Full disclosure: I met Bingham in 2017, when her play The Blue Hour of Natalie Barney premiered at the Arcola theater in London. After the play, Bingham and I briefly talked about varieties of lesbian relationships in the 1920s.)

Ackland and Warner became lovers in 1930 after passing three bliss-filled days and nights making love. This sexual passion cemented their relationship for life, along with Warner’s promise to “stand by Valentine always.” Ackland sowed the seeds of suffering for herself and others throughout her life by her flagrant sexuality. Warner absorbed the abuse in Christ-like fashion, accepting it without passing it on. Warner’s love was indispensable to Ackland’s sense of security. Each had something to give the other, something they alone could give.

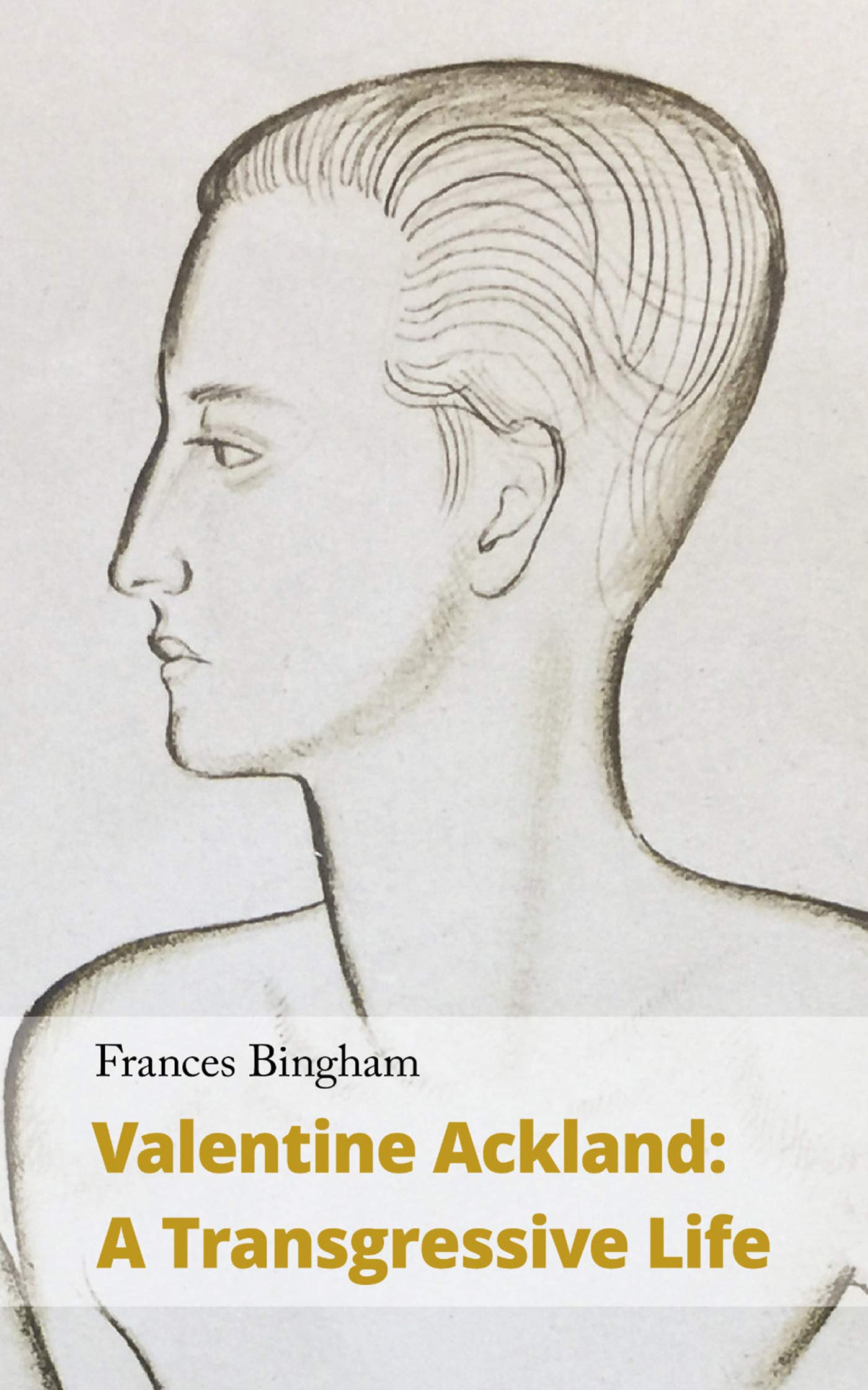

When they met, Molly Ackland Turpin was nineteen years old, almost six feet tall, and extremely thin. She could easily have been mistaken for an English schoolboy: pale, slender, reserved in the extreme, with a lock of dark hair falling over a high forehead. Despite being totally repulsed by her husband, Richard Turpin, she went through with the humiliating removal of her hymen so her closeted gay husband could impregnate her in his rape-like way of lovemaking. She did become pregnant, miscarried at five months, and spent years grieving this loss.

Predictably, Ackland’s Catholic family, especially her father Robert, was appalled by her “depravity,” and she was exiled from their household. Despite her masculine appearance, she did not identify as a transgender man (though she would probably identify as nonbinary or gender fluid in today’s terminology). With her direct gaze and swaggering performance of female masculinity, she joined many other “butch-babes,” including Romaine Brooks, Marlow Moss, Marion Barbara “Joe” Carstairs, Bryher, and Hannah Gluckstein (Gluck). Warner once wrote to Ackland: “the sex of your body, without prejudice to the rest of you, is female.” Her “masculine” skills included driving fast sports cars, repairing antiques, lighting her own cigarette, chopping wood, catching fish, and handling guns and knives. She was amused by the Freudian symbolism of her weapons.

Ackland was a fast-living, hard-drinking, but lonely person when she fell deeply in love with Sylvia Townsend Warner, a celebrity who had recently been photographed by Cecil Beaton. Warner’s dark hair was cut fashionably short. She wore horn-rimmed spectacles, which immediately identified her as a sophisticated “new woman.”

While she was courting Warner, Ackland enjoyed an uncomplicated affair with the ravishing Chinese-American film star Anna May Wong, who delighted in telling her: “If I could make love like you, I guess I’d father half the world.” Meanwhile, Warner was lonely and felt something was missing from her life. To Ackland she wrote: “I like your way of writing, the lines that are sleek and cold like the pebbles the sea has but just now left,” signing it “Your ever.” They moved in together in October 1930. Wrote Ackland to Warner: “I do not remember ever being comforted or supported by anyone through the whole of my childhood. I never had any sense of there being anyone I could turn to for protection or shelter.” Warner soon discovered her new lover’s insatiable need for reassurance had to be gratified on an ongoing basis.

In 1934, their wildly experimental book, Whether a Dove or Seagull, was published by Chatto. It featured over fifty poems by each author. Ackland was 27, hungry for success, with impossibly high expectations. They dedicated the book to Robert Frost, who wrote to poet Louis Untermeyer: “If you could have got along without two or three of the more physical poems… Don’t you find the contemplation of their kind of collusion emasculating? I am chilled to the marrow, as in the actual presence of some foul form of death where none of me can function.”

In their bios for the book, the publisher referenced Warner’s other works thus: “Ackland see Warner, S.T.” Ackland was furious and disillusioned. The incident exposed a side of her that Warner wished she hadn’t seen: envious and resentful of Warner’s greater success as a writer. They never collaborated on a writing project again. Warner didn’t publish another book of poetry for 25 years, so fearful was she of wounding Valentine’s fragile ego.

Gay, communist-inspired, and female, the women saw a rising tide of social injustice that they felt compelled to speak about on behalf of those lacking the skills or resources to speak for themselves. This led to their being blacklisted and monitored by M15. By age thirty, Ackland was drinking heavily and prone to deep depressions. She thought of herself as the husband in their relationship and decided it was her prerogative to seek other lovers. She slept around but remained committed to Warner, who occupied the position of the faithful spouse. Nevertheless, this arrangement led to many tensions in their relationship.

Ackland died of cancer at 63. Warner outlived her by almost nine years. Bingham has given us an admirable biography about a complex subject who was as beautiful to look at as she was difficult to love.

Cassandra Langer is the author of Romaine Brooks: A Life (Univ. of Wisconsin Press).