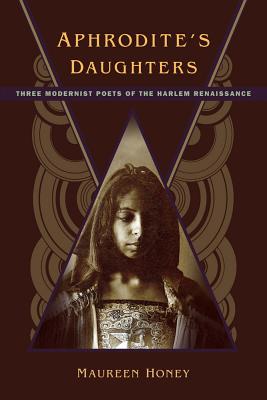

Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Poets of the Harlem Renaissance

Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Poets of the Harlem Renaissance

by Maureen Honey

Rutgers. 224 pages, $27.95

STUDIES of the Harlem Renaissance typically focus on black male figures such as Langston Hughes and Claude McKay. Not only are women typically underrepresented; indeed, the movement is often portrayed as being essentially a black male phenomenon. Thus, this study of three lesser-known female poets—Angelina Weld Grimké (1880-1958), Gwendolyn Bennett (1902-1981), and Mae Virginia Cowdery (1909-1953)—is a welcome departure. Adding to the intrigue is the fact that, broadly speaking, one of the writers could be considered the first openly black lesbian poet, and another was gender fluid or bisexual. (The third was straight.)

University of Nebraska professor Maureen Honey’s thesis is that these three black women appropriated the historically white myth of Aphrodite, reclaiming her as a black woman, thus creating a more identifiable conceit through which to view their experience. Though Honey does not push this thesis too hard, it’s a useful organizing principle and a good starting point for discussing the three women’s work. Not much is known about any of the three, particularly Cowdery; and none published much during her lifetime. However, Honey has done a remarkable job tracking down both unpublished work and biographical data on all three.

Angelina Weld Grimké was the mixed-race child of a white mother and a black father, Archibald Grimké, born a slave but rising to great prominence as a lawyer and diplomat. She lived in Washington, D.C., where she taught school for almost 25 years. Publishing her poetry in journals and magazines, Grimké was arguably the first African-American woman to publish lesbian-themed poetry. What’s more, her work seems startlingly fresh and sophisticated even today. It is also surprisingly frank. In the poem “Babette,” for instance, she states: “I love

Babette. … Last night when in the fields we met/ She paused and bade me tie/ Her britches string. Was it a net?/ I only know as she slipped by/ She raised me eyes I can’t forget.” The implication of illicit sexuality arising from the two women meeting in the fields and tying the string of their britches is clear—even startling—given that Grimké is writing near the turn of the century. Elsewhere, however, Grimké acknowledges the forbidden nature of the desire in references to “all the loving words/ I never dared to speak,” and, perhaps most movingly: “But I may never, never press/ My lips on thine in mute caress,/ E’en touch the hem of thy pure dress.” (“Thou Art So Far, So Far,” 1901). Grimké has a lovely, effortless intelligence in all the verse quoted by Honey, whose sleuthing efforts are all the more appreciated for that.

Gwendolyn Bennett was a New Yorker two decades younger than Grimké. In Honey’s analysis, one of the most interesting aspects of her work is her celebration of dark female sexuality as an alternative to the dominant white culture. Her most famous poem is “To a Dark Girl (1927),” where she confidently and defiantly states: “I love you for your brownness,/ And the rounded darkness of your breast. … Something of old forgotten queens/ Lurks in the lithe abandon of your walk/ And something of the shackled slave.” Though it may seem tame now, this assertion of beauty and sexual power in a nonwhite body was quite radical for its time.

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery is the work of the largely unknown Mae Virginia Cowdery. A young apostle of Langston Hughes, Cowdery, who was born in Philadelphia in 1909, seems to have been a rebel from the start. Early on, she had no qualms about openly expressing desire for both male and female lovers. The poem “Nameless” illustrates the beauty of her spare, unrhymed lines, as well as her frank eroticism: “No more/ The feel of your hand/ On my breast/ Like the silver path/ Of the moon/ On dark heaving ocean.” Letters to Hughes (whom she amusingly and affectionately calls “Lankey”) indicate that she is clearly addressing the poems to women, as when she asserts: “You may rest assured I wasn’t speaking of the ‘other guy’s’ red lips.” Complicating the picture is the fact that other poems are addressed to men. Indeed, she was married twice, and, given her talent and rebel nature, her disappearance into the role of wife seems both tragic and ironic.

If, in the end, Aphrodite’s Daughters leaves the reader wanting more, that’s perhaps a good thing, and perhaps it will serve to generate new interest in all three writers. For the time being, Honey has made a remarkable case for the restoration and addition of these three remarkable women into their rightful place in the canon.

Dale Boyer is the author of the novel The Dandelion Cloud. He lives and works in Chicago.