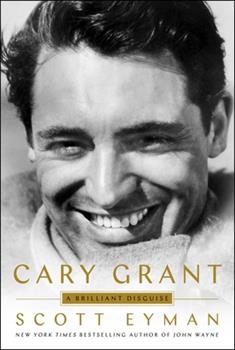

IN CARY GRANT: A Brilliant Disguise, author Scott Eyman argues that the persona we know as “Cary Grant” was an entirely fictitious invention of Archibald Leach. An ambitious lad from working-class Bristol, England, Archie fled his humble origins and by sheer grit remade himself into a debonair romantic lead and silver screen icon. Stunningly handsome, beautifully appointed in bespoke suits, always in fighting shape, and slyly charming, Grant was the object of desire for Hollywood’s leading ladies from the early talkies to the era of John F. Kennedy’s “Camelot” White House. His masquerade was so believable that even he had difficulty distinguishing his two identities.

Eyman also uses the word “disguise” to address more recent speculation about Grant’s sexuality. Was he, or wasn’t he? Eyman doesn’t come down firmly on either side but always remains open to the unlikely prospect that a man married five times could be counted as a “friend of Dorothy.” As if settling his own argument, Eyman wonders: “why would a theoretically gay actor in a tightly closeted time go out of his way to appear in hilarious drag—a fetching peignoir in Bringing Up Baby, while hopping up and down proclaiming, ‘I just went gay all of a sudden!’”

If the question of his sexuality is a frequent touchstone for Eyman, that of Grant’s childhood and family traumas plays an even greater role in the quest to understand his later career and private life. His parents were unhappily married, his father a drinker and his mother Elsie mentally unstable. She was sent off to a mental institution at her husband Elias Leach’s instigation. Archie, away at the time, returned home to the mystery of his mother’s disappearance. Elias would only reveal her whereabouts to his son more than a decade later when Grant, now an up-and-coming American actor, returned home to Bristol for a visit. Even so, she would not be released for many more years, by which time Elias was dead. Grant assumed responsibility for the care of his mother, with whom he maintained civil but strained relations.

Eyman portrays the adult Grant as a man who was conflicted, ashamed of his early status as a British music hall comic acrobat who followed England’s Pender troupe for an American tour and remained stateside to enter the vaudeville circuit. Having given up formal education in his teens and lacking any serious stage training, he managed to get undistinguished work on Broadway and eventually made it to Hollywood. There, his darkly handsome allure tipped the scales in his favor. Soon enough he was called upon to play opposite the blond and buxom Mae West, who was preparing to shoot She Done Him Wrong. Desperate to find a leading man, the brazen West saw Grant walking on the studio lot and declared him “the best-looking thing in Hollywood. … If he can talk, I’ll take him.” The film’s commercial success prompted another pairing of Grant and West in I’m No Angel. While he didn’t especially “impress the critics, the public, or his coworkers,” Paramount kept him around. The studio saw something in Grant “beyond good looks—a sense of something held in reserve.”

Among the English acting community on the Pacific Coast, Grant was aware that he lacked the classical training common to their set, so he plumped up his background to appear middle-class, turning his father Elias from a tailor to a clothing manufacturer and claiming a prep school education. But he was still beset with insecurities, with a “tetchy temperament on set,” and watched every dollar he spent, establishing his well-earned reputation of a tightwad, despite his taste for nice cars and clothes. Curiously, despite his good looks, he did not display an obvious narcissism, preferring to trade on his comic abilities to win over friends and audiences. On the other hand, he had a controlling disposition, both during movie shoots and in his many marriages.

His first marriage, to the actress Virginia Cherrill, moved forward despite the bride’s concerns about Grant’s “volatility, his jealousy and a temper that could easily ascend to rage.” Years later, she described him as “obsessive.” After she suffered a miscarriage, Grant unaccountably became jealous of any man who conversed with his wife. He didn’t want her to work and insisted that they stay home in the evenings, preferring to drink. “And when he’d had a drink or two and got angry,” Cherrill said, “he used to kick and hit me.” When she finally sued for divorce, there followed a contentious battle over alimony, and she added to the charge of physical abuse that he had “threatened to kill her.” While Grant privately complained that Cherrill accused him of being homosexual, she later denied ever saying this and, despite the passage of time, admitted to “carrying a torch for Cary for years after we parted.”

Grant’s hungry bachelor years as Archie Leach on the vaudeville circuit in New York included periods of seeking work through the National Vaudeville Artists clubhouse near Times Square. He lived on and off with an Australian named Orry George “Jack” Kelly in the heart of bohemian Greenwich Village. Kelly was friendly with such top vaudevillians as George Burns, Gracie Allen, and Jack Benny. The struggling Archie Leach met Burns when the latter was courting Allen. Burns taught Leach about timing and “ingratiating” himself with the audience since “it makes getting laughs easier.”

“Jack” Kelly developed a side business designing men’s painted neckties, which Archie Leach would sell on Broadway out of a suitcase, earning commissions. For Kelly, this was a prelude to his later success as Orry-Kelly, an esteemed costume designer for the movies. Kelly was decidedly gay, but when he later wrote about these early years, he made a point of mentioning Leach’s girlfriends, prompting Eyman to wonder “what besides financial desperation impelled Archie to room with a gay man.” Cary Grant’s friendship with Orry-Kelly soured over time, and he instructed his former roommate “to tell them nothing” if questions were raised about those early days in Greenwich Village. Still, Orry-Kelly insisted that there “was really never anything to hide.”

Orry-Kelly’s insistence that there was nothing to the rumors of Grant’s homosexuality, along with similar denials by some of Grant’s wives, sometimes has the tenor of “protesting too much.” Evidence offered for Grant’s homosexuality includes the early publicity stills of Grant and Randolph Scott from their years-long cohabitation in Hollywood, pictures that have since been widely disseminated on social media. Grant’s shared living quarters with Randy Scott near Paramount had been Orry-Kelly’s suggestion when he decided he’d had enough of Grant’s self-absorption and condescension. Neither Grant nor Scott was at the top of the Paramount food chain, but Grant was the more ambitious of the two. They’d met in 1932 as costars on the set of Hot Saturday, both cast as suitors to the same woman. They hit it off and began appearing “everywhere, social butterflies on a mad whirl.” When they roomed together, photos of the handsome pair in their sunny West Coast arrangement began to appear in movie magazines. Theirs was described as a “Damon and Pythias friendship,” though it wasn’t clear which man would be willing to die for the other.

Even Grant’s pursuit of his first wife did not loosen the men’s bond.

Even Grant’s pursuit of his first wife did not loosen the men’s bond.

Grant and Scott became the focus of several movie magazine articles whose titles walked a tightrope: “We Can’t Afford a Hollywood Marriage”; “Movie Bachelors at Home”; and as late as 1939, Photoplay’s “The Gay Romance of Cary Grant.” Eyman concludes that “either everybody was incredibly naïve, or the transparent bravado of Grant and Scott’s life together defused the obvious conclusion. People who refused to acknowledge they had anything to hide could not possibly have anything to hide.”

None of this would be worth the telling were it not for the celluloid guise that Grant fashioned to a T. Onscreen, he concluded that it was better to be chased by his female costars than for him to do the chasing. Furthermore, in the 1930s screwball comedies that solidified his early reputation, such as Bringing Up Baby, he brought “the gamut of emotions from dismay to frustration to several varieties of panic,” all matched to an array of physical tics, misalignments, and zany vocal inflections. Eyman is insightful in characterizing the qualities of Grant’s performances: “The basic joke, repeated … in most of Grant’s comedies, was the gradual but increasing discombobulation of his impeccable surface. … Cary Grant was invariably classy, but rarely dignified, at least not for long.”

He also brought a dexterous verbal wit to his performances, extemporizing where a director like Howard Hawkes confidently allowed it, as in His Girl Friday opposite Rosalind Russell. Brash newsman Walter Burns (Grant) is trying to lure his ex-wife, Hildy Johnson (Russell), also an aggressive news reporter, away from her new fiancé and back into his own clutches. Burns/Grant breezily claims that Hildy’s fiancé looks like “that fellow in the pictures—you know, what’s his name—Ralph Bellamy.” Ralph Bell- amy was in fact playing the hapless fellow, injecting what Eyman calls a “meta before meta” cultural reference. In a film whose rat-tat-tat dialogue was delivered at an amazingly fast pace, Grant proved himself up to the task. Grant’s character Walter Burns dismisses a threat by quipping: “The last man to say that to me was Archie Leach, just a week before he cut his throat!” Rosalind Russell matched Grant’s high-speed delivery and moxie, representing for her generation what independence-minded women meant when they dreamed of pursuing careers rather than marriage.

With exceptions, much of Grant’s early career traded on his physically fluid comic performances opposite such female stars as Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby and Holiday or Irene Dunne in The Awful Truth. The latter, directed by Leo McCarey in a footloose style, demanded of his actors an equally relaxed and improvisational demeanor. So, Grant mumbled under his breath, expressing frustration amid his character’s growing alarm. He might still look like a leading man, “but his willingness to play the fool implied an indifference toward his own good looks.” Critic Pauline Kael credited Grant with bringing “elegance to low comedy and low comedy gave him the corky common-man touch that made him a great star.”

Director Alfred Hitchcock, a fellow working-class Brit, likewise outwardly cheerful, brought a different hue to Grant’s acting palette. First in Suspicion opposite Joan Fontaine and then in Notorious opposite Ingrid Bergman, darkness descended. The scripts brought out an undercurrent of menace in Grant that showed him capable of being a cad. In his late Hitchcock movie North by Northwest (1958), when Grant’s character Roger Thornhill discovers that his love interest, Eva Marie Saint, is a double agent, he denounces her in the sharpest of terms, revealing a sourness and contempt that rarely surfaced in his performances. Years after their work together, Hitchcock credited Grant as the one actor who could fake a charm that he did not in fact possess.

What Grant did possess was an almost cutthroat ambition that allowed him to break free of the studio system in favor of a freelance career. That way, he could accept a smaller paycheck while getting a percentage of the gross on a given film. Such arrangements worked to his advantage and enabled him to save up for a comfortable retirement. His second wife was the heiress Barbara Hutton, related both to the Woolworth family and Wall Street’s E. F. Hutton. She was believed to be the richest woman in the world. While the marriage might suggest a degree of calculation on Grant’s part, others saw real affection between the couple. But it didn’t last. Grant renounced any claim to her money, and eventually there followed three more marriages.

When he met his fourth wife, actress Dyan Cannon, in 1961, she was a voluptuous 22-year-old and he was a well-preserved 57. He had become a devotee of the hallucinogen LSD, which he took under medical supervision and occasionally persuaded Dyan to take with him. Grant found that it helped him with many of the internal anxieties and depressions that had plagued him throughout his adult life. He proselytized on its behalf even as the hippie generation embraced its cause. But it could not save a marriage in which, according to Cannon, Grant was forever guiding her domestic upkeep and condescendingly explaining how to do nearly everything.

However, this marriage produced Grant’s only child, an adored daughter named Jennifer. She was undoubtedly one of the great comforts of his mature years when Grant finally resolved that he was too old to be making onscreen love to younger women and wearied of the demands of stardom.

Once he became a brand name, Grant cossetted his reputation as a deliverer of sophistication and charm by avoiding roles that might require him to stretch beyond this comfort zone. He’d been nominated twice for an Oscar: in 1941 for George Stevens’s Penny Serenade, a domestic drama with emotional heft in which Grant was forced to break down and cry; and in 1944, for None But the Lonely Heart, written and directed by Clifford Odets, in which Grant played an embittered Cockney man, which allowed him to call upon his working-class roots and his internal conflicts. From then on, Grant’s name always appeared above the title of his films, but he was determined to give the audience what it had come to expect: his light and breezy comic touch.

As for his private reputation, in his last years he toured American cities and towns in a one-man colloquy with audiences titled “A Conversation with Cary Grant,” with his fifth and final wife, Barbara Harris, dutifully by his side. If during the Q&A the names of either Sophia Loren (it’s complicated) or Randolph Scott (see above) were invoked, an uncomfortable silence would follow before he moved on to the next question.

In the mid-1970s, between marriages, Grant kept company with a much younger English writer named Maureen Donaldson, who brought into their tight circle her friend Bill Royce. Royce might house-sit for Grant when he and Donaldson were away. Royce found that he and Grant shared similarly difficult beginnings, and this allowed Grant to open up to the younger man. Royce eventually “unburdened himself” about his bisexuality and, as Eyman puts it, “Grant responded by implying he had been basically gay as a young man, later bisexual, still later straight.” Given Grant’s history, it would be easy to imagine all of this. He was an attractive teenager who had traveled in the rakish company of British music hall performers and vaudevillians. He may well have been a target of interest and, if so inclined, might have found the attention appealing and gay sexual adventures good sport. Getting to Hollywood, the menu was wide and varied, and playing both sides of the fence was undoubtedly irresistible. But Grant wanted a family and sought a parental role—such as with Barbara Hutton’s son Lance and Clifford Odets’s son Walt. He mentored younger people sympathetically. And, according to Royce, he didn’t think homosexual acts were shameful, only “part of the journey, not necessarily the final destination.” Given the times in which he lived, Grant preferred to keep his audience guessing.

As for his relationship with “Randy Scott,” you’ll have to read Eyman’s sensitive if sometimes dark account of Grant to draw your own conclusions. Eyman provides background on the Hollywood studio system and its many players while sounding the depths of Grant’s emotional turmoil. Randolph Scott’s place in the puzzle of Grant’s emotional life is best discovered by reading this often entertaining but sometimes intentionally confounding life story of one of Hollywood’s great stars.

Allen Ellenzweig, a longtime contributor to this magazine, is a cultural writer based in New York City.