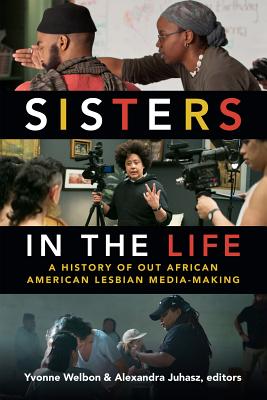

Sisters in the Life: A History of Out African American Lesbian Media-Making

Sisters in the Life: A History of Out African American Lesbian Media-Making

Edited by Yvonne Welbon and Alexandra Juhasz

Duke University Press. 296 pages, $26.95

IN HER INTRODUCTION to Sisters in the Life, editor Yvonne Welbon explains the significance of the “minority group” under discussion, namely African-American lesbian filmmakers: “Since the 1922 theatrical release of Tressie Souders’s A Woman’s Error, approximately one hundred feature films have been directed by African-American women. Almost one-third of those films were directed by black lesbians. Statistically about four percent of the adult American population is likely to identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, but over thirty percent of the feature films have been directed by this minority population.”

Who knew? The editor goes on to say that Ava DuVernay’s current Hollywood film, A Wrinkle in Time, now has the biggest budget ($100 million) of any film directed by an African-American woman. This scholarly book is clearly intended to fill a gap in film studies as they have traditionally been taught. Both of the editors remark that this is the book they needed to read when they were fledgling students and filmmakers looking for evidence that women who resembled them in any way had ever created a cinematic legacy.

The anthology is divided chronologically into two sections: “Part I: 1986–1995” and “Part II: 1996–2016.” Essays in the first part include an analysis of panel discussions, visual art, and sculpture, as well as film, and all discuss the need for queer black female authenticity. In the title of “Birth of a Notion,” filmmaker and academic Michelle Parkerson refers to the notorious 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation, which featured white actors in blackface and showed sympathy for both the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan. Parkerson’s essay is subtitled “Toward Black, Gay, and Lesbian Imagery in Film and Video,” and it explores the challenge of overcoming the invisibility and stigmatization of LGBT characters within the African-American community. She sees a “new generation of gay and lesbian filmmakers of color” on the horizon.

The interdisciplinary, multimedia approach of the editors allows them to include a diversity of voices. There is some discussion of the work of heterosexual and gay male artists and artistic representation, and this material places lesbian filmmakers in a broader cultural context. On the other hand, it does dilute the specific focus on African-American lesbian filmmakers.

The last essay, “Creating the World Anew: Black Lesbian Legacies and Queer Film Futures,” by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, discusses two projects: the Queer Women of Color Media Arts Project in San Francisco, and the Queer Renaissance and Black Feminist Film School Project in Durham, North Carolina. Both are described as efforts to provide training in film production as part of a “futuristic movement.” In an effort to be “transparent,” Gumbs explains: “Yvonne Welbon, the editor and initiator of this book, and other contributors have participated in the activities of both or one of these projects, and this is as it should be. The future of Black lesbian filmmaking is not something about which we can be objective; it is something we do.” Some might criticize this bold rejection of detachment, but, as a number of the contributors remind us, those engaged in creating cultural visibility can’t afford to make critical distance a priority in their work.

Black-and-white photos of actors, artists, scriptwriters, directors, and panelists break up the pages of prose. Even a casual viewer of film and television dramas is likely to come across a few familiar faces. Despite the academic tone of most of the essays, the collection as a whole conveys the energy and camaraderie of artists in the midst of revolutionary change. This is an eye-opening study that seems likely to become a classic in its genre.

________________________________________________________

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Canada.