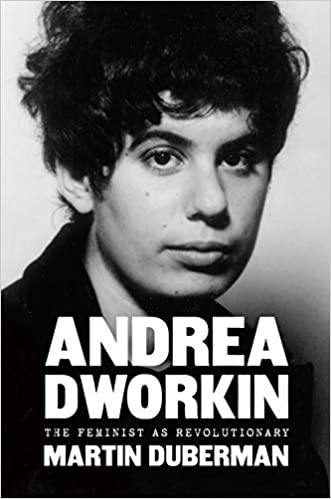

ANDREA DWORKIN

ANDREA DWORKIN

The Feminist as Revolutionary

by Martin Duberman

The New Press. 384 pages, $29.99

RECENTLY a student said to me: “No one has seen women the way that Andrea Dworkin saw us.” In fact, I think few have seen the human condition with as much clarity as Andrea Dworkin did. Still fewer writers have dared to write the truth about it in the way that she did. She was a force both destructive and liberating. And that caused her to be feared, hated, and much maligned. The brutal, misogynistic, often pornographic caricature of her as a hyperbolic manhater who thought all sex was rape (she never said that) is alien to anyone who has actually read her work; but it stuck. The real Dworkin was often eclipsed by it.

I never got to know her personally in any real sense. However, because some of her loved ones and close friends—namely John Stoltenberg and Catharine MacKinnon, who figure prominently in this biography—have also been my close friends and professional collaborators for many years, I have often felt as if I knew her. The woman who emerged for me through the eyes of her loved ones was multifaceted, vulnerable, uncompromising, easily wounded, fiercely protective of her work, and convinced of her entitlement to a creative life. She was a personality, like most, riven with contradictions, only more so—softness, compassion, fury, and a huge capacity to love that was shot through with a steely survival instinct and the resolve to cut offenders out of her life with surgical precision and without any apparent doubt as to the necessity of her actions. They sometimes included erstwhile close friends, among them Martin Duberman, the author of a recent biography titled Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary.

While Duberman ferrets out this private side of Andrea Dworkin with aplomb, the public Dworkin, “huge and hollering,” as Ariel Levy once put it, is ever-present too. The events of her political career, often inseparable from her private hurts, are examined: her time in the New York Women’s House of Detention; the sadistically abusive husband who nearly killed her; her central position in the women’s movement, especially in the 1970s and ’80s; and, of course, her zealous attack on pornography as a form of sexual abuse. It is the last of these that made her the target of the pornography industry as well as some in the gay community who accused her of “anti-sex” censoriousness. The picture of Dworkin that emerges in this biography is consistent with her reputation as a fierce, difficult woman.

Duberman’s biography coincides with a notable revival of interest in Dworkin’s work—a recently published collection of her writings, Last Days at Hot Slit, got more press than any of her work published during her lifetime—and Duberman’s treatment of her as a fully human personality advances the argument that old labels should not impede an honest assessment of her work. His adroit handling of the complexities of her personality leaves one feeling that, however difficult a friend she may have been to make and keep, it would have been worth the effort. Duberman illumines her work in some depth, but the major contribution of this book is in the way it foregrounds Dworkin’s fundamental humanity. Readers whose lives have been upended by her provocative insights will undoubtedly see her work with a new clarity.

For many years, I’ve shown a documentary in one of my free speech seminars in which Andrea Dworkin appears and speaks for herself. Students often remark on the stark contrast between the Dworkin they read in their assignments and the soft-spoken woman in the film, who is rather self-effacing and so obviously earnest in her concern for the forgotten, victimized women that she wrote about. Once they encounter her “in person” in this way, many demonstrate a noticeable softening towards her, as if her personal presentation should cause them to re-evaluate her work. I’ll admit to my reservations about this reaction, but if Duberman’s presentation of the complicated, vulnerable person the students were able to see in this footage encourages a fairer reading of Dworkin’s important work, unencumbered by the old caricatures and the lies, then his book may amount to a measure of the justice she was usually denied in life.

Shannon Gilreath is professor of Law and of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Wake Forest University. He is the author of The End of Straight Supremacy and other books.