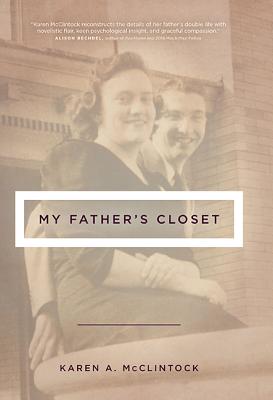

My Father’s Closet

My Father’s Closet

by Karen A. McClintock

Ohio State University Press. 256 pages, $29.95

WRITING in a recent issue of The New Yorker, Daniel Mendelsohn describes taking a trip with his elderly father. In the article, he remarks: “Our parents are mysterious to us in ways that we can never quite be mysterious to them.” What Mendelsohn means, I think, is that, while we are in full view of our parents as we grow up, our parents are only revealed to us little by little as we mature and make discoveries about them, often at the same time as we are making discoveries about ourselves.

Making discoveries—sometimes unwanted ones—is the subject of McClintock’s memoir, My Father’s Closet.

McClintock’s father, Charles, who was affiliated with Ohio State University, seems always to have been a bit hidden and aloof. Outwardly, and in journals he kept during World War II, he was a devoted family man, part of the prevailing heteronormative culture of America in the 1950s and ’60s. And yet, there was ample evidence all along that this was a convenient façade to hide behind as he wrestled with his true nature. At some point, Charles finally meets a German Jewish refugee named Walther Michael who seems to have become the love his life. When Walther is killed in a plane crash in South America, his death sends Charles into a depression so deep that the strength of his attachment becomes impossible to ignore.

The evidence the author accumulates over the years regarding her father’s true sexuality is intriguing: an oddly uncomfortable painting of a hustler looking at a client that Walther gave to Charles as a gift; the frequent visits he took with Walther to New York; the increasingly Platonic relationship between her parents, which they would never acknowledge or discuss. At one point, McClintock’s grandmother tells her a bit too emphatically that she really does believe that her mother and father love each other. And yet, at Charles’ funeral, she leans forward and says: “You have no idea what your mother has gone through.”

Eventually, of course, the truth comes out. The day after Charles’ funeral, her mother tells her pointedly: “Honey, you were our last sex.” Many years after that, McClintock finally reads her father’s journals and discovers an uncharacteristically frank—even exuberant—description of a sexual encounter that her seventeen-year-old father had with a male friend. Vindicated in her suspicions at last, McClintock begins having discussions with a frequent male visitor to the house, and he confirms for her that her father was, in fact, gay. The author details a fairly typical set of reactions, including disbelief and anger before finally settling into acceptance. There are many instances in which McClintock notes the ripple effect of her father’s secrecy on her own and her sister’s marriage. This leads to the interesting speculation that such a background may have led McClintock to pursue a career as a psychologist.

To her credit, McClintock works not only to piece together her father’s story but also to imagine his struggle and anguish through it all. And yet, this is precisely where My Father’s Closet runs into difficulties. There’s always something queasily uncomfortable about imagining your parents’ sex life, but there’s something almost voyeuristic in her imagined descriptions of Charles’ relationship with Walther. Unfortunately, too, the dramatizations are often thin and unconvincing. Too often, she not only takes this awkward path, but then proceeds to call even more attention to her own authorial intrusion: “Grandma, from her place in heaven, has given me permission to fill out the story since I’ve heard it from several viewpoints over the years. She deserves full credit for my skill at this.”

The cumulative effect of this approach is that the reader doesn’t know whether to believe that something actually happened or is only being imagined. This is perhaps unavoidable, since, as we learn late in the book, her father largely stopped writing letters, and kept no journal, after the War. Thus, for example, when her father tells himself “I don’t deserve all this” as he builds a new home or comments on Walther’s flamboyance on a weekend trip to New York, the reader might be forgiven for wondering how she could know these things. As admirable as My Father’s Closet is in many ways, the book often sits uncomfortably between a desire to get to the truth of her father’s struggle and an urge to dramatize the unknown details of his life.

________________________________________________________

Dale Boyer is the author of The Dandelion Cloud.