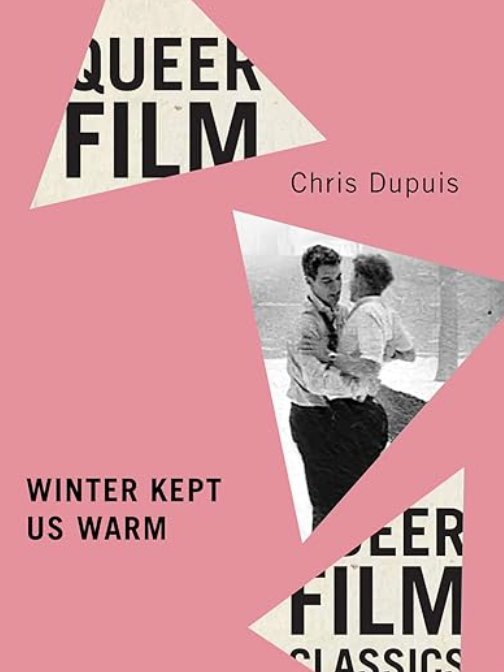

WINTER KEPT US WARM

WINTER KEPT US WARM

by Chris Dupuis

McGill-Queen’s Univ. Press

124 pages, $19.95

WHEN the Canadian film Winter Kept Us Warm was released in 1965, no one, including the director and producer David Secter, a 22-year-old English major at the University of Toronto with no prior filmmaking experience, believed it would become Canada’s first successful independent film. But despite its critical success, within a decade the film had been all but forgotten. Chris Dupuis’ important book, the latest volume in McGill-Queen’s Queer Film Classics series, attempts to answer the question: “How does a film so radical in its approach, so lauded upon its release, and so important to the history of queer and Canadian cinema, virtually disappear?”

The film’s plot is autobiographical, inspired by Secter’s own brief friendship with—and unrequited crush on—a younger student at the University of Toronto. It tells the story of the relationship between Doug (a popular senior) and Peter (a freshman) at the university over the course of the school year. The two students first meet at a hazing in the dormitory cafeteria. Later, in the library, where Peter is borrowing a copy of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (from which Secter takes his title), Doug apologizes for his earlier conduct, and the two begin a friendship that culminates in an erotically charged romp in the first snowfall and, after the winter carnival, a shower scene in which they soap up each other’s backs. But after Christmas break, things become complicated when Peter starts dating an older girl (Sandra) and Doug’s long-time girlfriend suspects that he is more interested in Peter than in her, which Doug denies. The film’s climax occurs when Doug assaults Peter after learning that he’s had sex with Sandra. Doug returns to the library and rereads The Waste Land, which he had tried to read but “couldn’t make sense of it.” In an epiphany, he finally begins to “make sense” of his true feelings for Peter and of his own sexuality.

Despite a budget of only $8,000 Canadian and a number of technical weaknesses, the film enjoyed early success. In April 1965, three months before shooting concluded, Secter got a letter from the Commonwealth Film Festival in Cardiff, Wales, inviting him to submit the film. Early in 1966 it began a six-week run at the Pace Theatre in Winnipeg, followed by two weeks at Toronto’s Elektra Theatre, and during that run Secter learned that the National Film Board (the largest film-production entity in Canada) had selected it as Canada’s entry in the Cannes Film Festival’s Semaine de la Critique, where Secter got to mingle with celebrities and dine with Sophia Loren, who was that year’s Jury Prize president. Back in Canada, the film was screened at the Montreal International Film Festival in 1966, where it received a Special Jury prize “in recognition of its ambitious young film-maker, and for his great sensibility and lack of pretentiousness.” In late 1967, it found a distributor, New York’s fledgling Film-Makers’ Cooperative, which secured a six-week run at the New Cinema Playhouse. Screening in New York and later in L.A. helped to generate critical attention to the film, which Variety praised for its “appealing handling of a heavily implied but not activated homosexuality.”

And then the film virtually disappeared, largely because of its pre-Stonewall reluctance to deal directly with gay subject matter. With the more politically engaged queer films that emerged after Stonewall, the film was simply ignored. Dupuis recalls that when he first saw the film in the early 2000s, he was unimpressed: “At that time, I was trying to expand my know-ledge of queer cultural history … hoping for a life-changing experience. In the end all I saw was a glitchy black-and-white film with choppy editing and stilted dialogue. I left disappointed and Winter quickly faded from my mind.” But when he saw it again years later, “my experience was radically different. An archaically dull picture that had barely sustained my attention was now a heart-wrenching portrait of longing, confusion, and unrequited love.”

In judging the film, we must, as Dupuis points out, realize that “Secter was creating the work at a time when homosexuality was a crime in both Canada and the U.S. He was working on a university campus, an environment just as homophobic as the broader culture, if not more so. And he wasn’t working within a queer community. … Instead, he was collaborating with a team of straight people at a straight institution, and so he had to consider the ramifications if the project were to ‘come out.’” Many of those involved with the making of the film, including the actors, were not aware of its gay themes. Moreover, Secter was anxious to make a commercially viable film that could be shown in major theater chains rather than only in art house cinemas.

Winter Kept Us Warm is long overdue for a reassessment. As Canadian film historian, critic, and gay rights activist Thomas Waugh told Dupuis: “It’s so important for a film like this to be preserved, because it really speaks to what it was like to be gay in this time and place. It’s a way to pass on to future generations who have no other way to access it.” Happily, you can judge for yourself: the film is available for viewing on YouTube and on Internet Archive.

Nils Clausson is emeritus professor of English at the University of Regina in Manitoba, Canada.