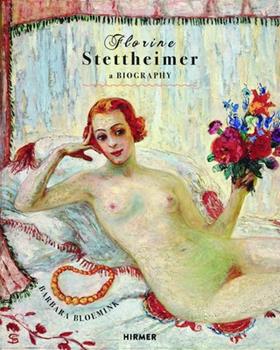

I WAS FULLY INTRODUCED to the “eccentric” art of Florine Stettheimer when the Jewish Museum in New York City mounted a major retrospective in 2017 (Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry). Until then, I had mostly been aware of her as the costume and set designer for the landmark Gertrude Stein-Virgil Thomson avant-garde opera Four Saints in Three Acts, which premiered in the U.S. in 1934.

I know a good deal more about Stettheimer now thanks to Barbara Bloemink’s new biography of the artist. Bloemink revises the previous profile of Stettheimer as a “cloistered spinster” or an “eccentric maiden aunt.” She corrects the impression, fostered by gay film critic Parker Tyler’s 1963 commissioned biography, that a “timid” and “hypersensitive” Stettheimer was unable to encounter the world as a fully realized, capable woman. For example, Tyler incorrectly claimed that Stettheimer was so “devastated” by the lack of sales from her earliest 1916 exhibition that “she never (or rarely) exhibited publicly again.” Finally, Bloemink wants to overturn earlier commentary that dismissed Stettheimer’s œuvre with such terms as “naïve” or “overly feminine,” resembling “puff-pastry” and compared to “outsider” or “children’s art.” The work, in short, has been treated with condescension, and the artist widely misunderstood. (That said, I do demur from finding Stettheimer’s paintings of flower bouquets worthy of deep reflection.)

Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944) had a privileged upbringing as one of five children whose parentage was German-Jewish, although also Dutch Protestant on their maternal side, and decidedly privileged financially.

In their youths, the Stettheimer girls lived with their mother in Stuttgart, with complementary travels throughout Europe. Florine painted even as a child and had regular art training, while also studying at a school for “upper-class” girls. In the late 1880s, the Stettheimers spent a part of each year in Berlin, but they returned to New York by the early 1890s. Florine enrolled in a four-year program at the city’s Art Students League, which maintained a liberal attitude toward female students, enabling Florine to take life drawing classes from the male model. Her early nude studies confirm a facility with the realistic rendering of the human form. And in the beginning of the new century, Florine took up various media, from colored crayons to oils applied thickly with palette knife. Similarly, contemporary European influences in her work—the Symbolism of the late 19th century, Fauvist color, and Pointillist and Postimpressionist approaches—demonstrated her willingness to experiment and to reject a modish orthodoxy.

Bloemink’s stress on Stettheimer’s formal training shores up her position that she was no naïve. Her early portraits, like a somber one of sister Carrie, evince an academic command. And a self-portrait from 1914-1916 shows Florine in artist’s smock, right hand clasping a wooden palette and paint brushes. She presented herself as a professional, confirming to her dubious mother and sisters that she was no dilettante.

Stettheimer’s choice of métier was not typical for a woman of her class and social situation. She was “brought up under the cloak of gentility and enforced social rules”—what Bloemink characterizes as “the hermetic, financially comfortable world of New York’s prominent German-Jewish members.” Nevertheless despite the Stettheimer cocoon of female domesticity, there were tensions and jealousies, especially between the intellectual but “extrovert” Ettie and the sharp-witted, ambitious Florine. The former was among the first women to earn a bachelor’s degree at Barnard, and later, in Germany, a doctorate in philosophy, while Florine’s observant and sly paintings sometimes revealed the inner life of their female clan in plein air summer scenes that included the avant-garde individuals who were the family’s guests. Ettie was both skeptical and envious of Florine’s public successes as a regular exhibiting artist—although this was always in large group shows. In this respect, Parker Tyler’s exaggerated claim is not without some basis: Florine’s first solo show in 1916 was the last such venture. Her next one, curated by her friend Duchamp, occurred after her death at the Museum of Modern Art. In between, Florine rejected invitations to join prominent galleries, even if invited by a prominent friend like Alfred Stieglitz. It was also her policy to ask for wildly exaggerated prices for her paintings, even when desired by friends or notable art connoisseurs, so that Florine remained the best collector of her work. I wish Bloemink had grappled more decisively with her feminist subject’s almost perverse tendency to undermine her own career.

Stettheimer’s capacious talents—she took enormous care with her home décor, frequently incorporated hand-crafted frames on individual paintings, and wrote poetry that was piquant, pithy, and capable of more than one mordant quip—were distilled by her Parisian encounter with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Evidence that she was no prudish old maid or lesbian is confirmed in several diary entries, including her delight in Nijinsky’s shocking erotic performance in L’après midi d’un faune in 1912: “I saw something beautiful last evening … Nijinsky the Faun was marvelous—he seemed to be true half beast if not two-thirds … he was as graceful as a woman. … He is the most wonderful male dancer I have seen.”

In 1920, Stettheimer would place Nijinsky at the center of her painting Music, where, in a pose from another Ballets Russes offering, Le Spectre de la Rose, she “deliberately changed Nijinsky’s costume … to create an implication of distinctly erotic bisexuality. … Its strapless, heart-shaped bodice-like front reveals the cleavage of a woman’s breasts.” The dancer, arms above his head, is positioned on the toes of his ballet shoes. At the time, Nijinsky was one of the few male ballet dancers able to dance en pointe. Stettheimer had obviously lost none of her enthusiasm for his indefinite gender qualities and emphasized them, which Bloemink takes as a particularly “provocative act” for the period. Within the year of Music’s completion, Bloemink tells us that the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice encouraged police raids at the Everard Baths, a favorite of the city’s gay men, and there were “numerous arrests and jail time for lewd behavior.” By 1923, a city law “prohibited loitering for sodomy within city limits.” Despite this, the Stettheimers continued to allow their salon to be a refuge “for their many friends to be open about their sexual preferences.”

As for the production of Le Spectre de la Rose, Stettheimer commented on how lucky its designer Leon Bakst was as a painter and designer to be “able to see his things executed.” She was so stagestruck that she spent several years writing the libretto and designing sets and costumes for an original ballet she hoped to see produced by the Ballets Russes. Bloemink concludes that, in Stettheimer’s drawing plans and three-dimensional “puppets” dressed as presentation models, the artist “developed the exact style, flattened manner, and active gestural forms and implied movement that later formed the basis of her unique mature painting style.” This experience undoubtedly informed Stettheimer’s rich colorful costuming and striking cellophane backdrops for the 1934 Four Saints in Three Acts, seen by many as the crucial ingredient that held the entire production together.

Her “mature” style was already forming in the 1910s, when Florine documented sometimes crowded scenes of activity in outdoor settings, as in Sunday Afternoon in the Country (1917) with its far-reaching view. Theatrical in composition, the scene shows tiny but identifiable figures engaging in various anecdotal activities downstage and centerstage, while the distant perspective might be described as a lavishly decorated scrim. Another such “busy” scene is a testament to her friendship with the title’s subject, La Fête à Duchamp (1917), where horizontal bands of color distinguish present daytime action, a tea party on a sunlit yellow lawn, from the later nighttime birthday celebration for Marcel on a purple-violet lantern-lit terrace across the top of the canvas. Here, as in other later paintings, Stettheimer presents a confluence of time sequences, what Duchamp himself termed her “multiplication virtuelle,” which tracked with the work of her favored writer, Marcel Proust, whose In Search of Lost Time takes the reader on a journey through a reawakened past.

It is Stettheimer’s four-painting sequence The Cathedrals of New York that are generally considered the summit of her painterly achievement. Produced from 1929 to shortly before her death from cancer in 1944, this quartet documents the energetic New York of post-World War I: its popular movie and theater palaces amid gaudy advertising and street lights (The Cathedrals of Broadway, 1929); an ostentatious society wedding surrounded by ads for luxury purveyors of jewelry, bridal gowns, and chocolates, while the bride and groom at center present themselves to a fashionable public and a formal wedding photographer (The Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue, 1931); the pomp and flag-waving pageantry of a patriotic celebration to commemorate the 150th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration amid the banking institutions of the Financial District and the U.S. Stock Exchange (The Cathedrals of Wall Street, 1939); and a lavish columned interior with central carpeted staircase where the mandarins of the city’s competitive institutional art world—The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art—shelter within their assigned alcoves near the impressive stairway whose steps are populated with a host of art-world luminaries (The Cathedrals of Art, 1942–1944).

The panoply of incidents in these canvases produces an array of figures disporting in movement or standing in solemn salute to the proceedings. Stettheimer’s figures are often rendered as slender and malleable as rubber; they recall some of her earliest group scenes where female or male figures appeared slim and slinky as salamanders. Even in her marvelous 1928 grisaille portrait of a standing Alfred Stieglitz, draped in his signature black cape, the imposing gallerist’s dark silhouette ends in tiny feet shod in black. Similarly, a 1922 seated portrait of Carl Van Vechten has the writer dramatically posed at odd angles in a dark suit; he is surrounded by a room carpeted red and full of objets and books. Arms and legs crisscrossed in an effete manner, his red tie, and exposed violet socks, code Van Vechten’s homosexuality even as Stettheimer references his marriage to the actress Fania Marianoff. But the figure’s lean angular frame ending in small hands and tiny feet are a declaration of Stettheimer’s intentional turn from the realism of the academy to a vaguely Surrealist manner that, finally, is sui generis, like the entirety of her life and work.