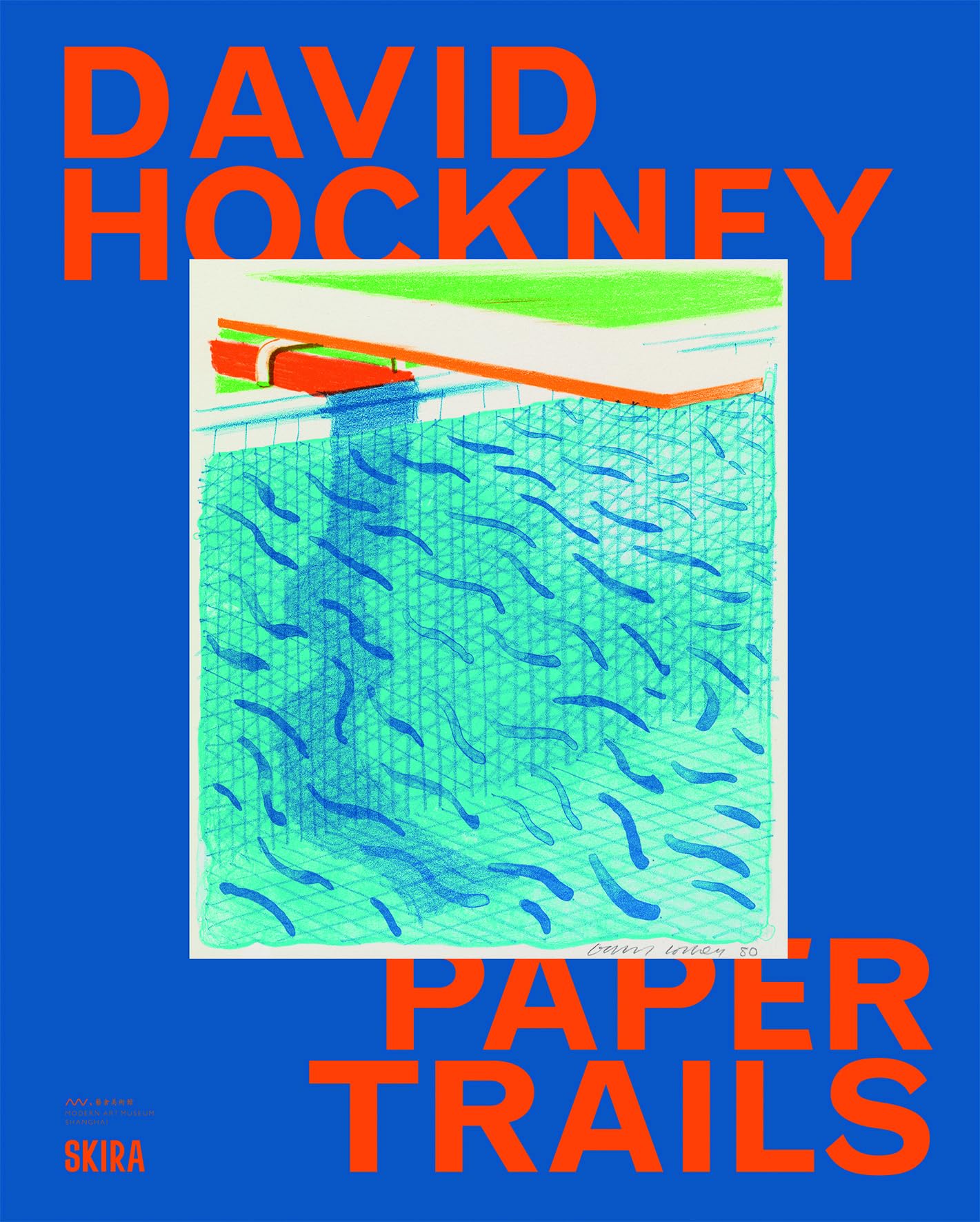

DAVID HOCKNEY: Paper Trails

Edited by Shai Baitel

SKIRA. 221 pages, $65.

I WELCOME any chance to see artworks by David Hockney, directly or through printed reproductions; but David Hockney: Paper Trails is not what I had hoped for. The book serves as the catalog for the Modern Art Museum Shanghai’s Hockney exhibition, which opened last June—a fact that explains some of the book’s limitations.

The curator’s idea was to focus only on Hockney’s “works on paper,” a category meant to include lithography, etching, photo collage, prints made from iPad drawings, and what Hockney calls his “photo drawings.” Not included are any examples of his traditional draftsmanship (done of course on paper), even though the drawings he made with color pencil in the 1970s are among his most brilliant works. Further, very few of his early pieces in the medium of etching and aquatint are included—disappointing for the readers of this magazine, given the homoerotic character of many of those etchings. None of them appears in this volume. To be fair, it’s true that as Hockney aged, he moved away from gay-themed subjects, and this show is composed for the most part of recent work.

Hockney’s major fame is based on his paintings, partly because he moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1960s and found the light, color, palm trees, architecture, swimming pools, and hedonism of Southern California congenial for painting. His treatment of all these subjects was inflected by his experience and sensibility as a gay man, an array of personal choices confirmed and accentuated by the gradually accelerating exit of other tenants from their airless closets. The new sexual freedom was emblematic of a more general freedom in both life and art. Describing his move to the city, he said: “Within a week of arriving there in this strange big city, not knowing a soul, I’d passed the driving test, bought a car, driven to Las Vegas and won some money, got myself a studio, started painting, all in a week. And I thought, it’s just how I imagined it would be.”

Despite the acclaim his paintings won, Hockney never abandoned printmaking, especially if you place photographic and digital experiments under that rubric. As with Jasper Johns, his graphic work runs a close second in importance to his paintings. It seems likely that Hockney, more literate than most painters, read Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” an essay whose conceptual underpinnings were inseparable from photography. Hockney never became a photographic artist in the sense that Berenice Abbott and Robert Mapplethorpe were. Instead, photographs were simply one step in the process of making a comprehensive artwork that incorporated photographic images. The key example is Hockney’s technique of collaging together a “mosaic” of dozens of Polaroid snapshots into a single work. Each photo would be taken from a slightly different angle, so that, once they were joined together, the aggregate would offer multiple overlapping views of a given subject. The result could be described as the photographic equivalent of Cubism in painting.

I assume these photographic aggregates were what prompted Hockney to explore another aspect of visual representation: the technique of Renaissance perspective, which gives the illusion of spatial distance by constructing an image around a single vanishing point. Reversing or subverting the foundational rules of perspective has consistently preoccupied Hockney in his later phase. One work in this catalog includes the written phrase “Perspective Should Be Reversed,” and to the extent that such a reversal is possible, the image does so, moving the vanishing point into the foreground rather than the background of the picture. Other works use multiple vanishing points in the background, forming a kind of Cinemascope presentation of a landscape or an interior space. It’s as though a camera has panned in a left-to-right semicircle to achieve the final still image. Hockney’s concern with perspectival experiments might seem pedantic or unduly technical, less engaging than his representation of human subjects, but I see them as conscious or semiconscious expressions of his sexual orientation. In this framework, they qualify as manifestations of the LGBT initiative to deconstruct inflexible rules about what is natural and normal in favor of transformative reversals and an antinomian pluralism.

Putting aside all technical or sociological aspects of Hockney’s work, we can enjoy his pictures simply as brilliant and inventive visual experiences—surprising excursions into a realm of color, fruitful allusion, and kinetic design. This catalog includes portraits in a number sufficient to remind us that, in addition to his technical investigations, Hockney was always concerned with the human subject negotiating familial affection, friendship, physical pleasure, and conjugal love.

Alfred Corn has published eleven books of poems, two novels, and three volumes of critical essays.