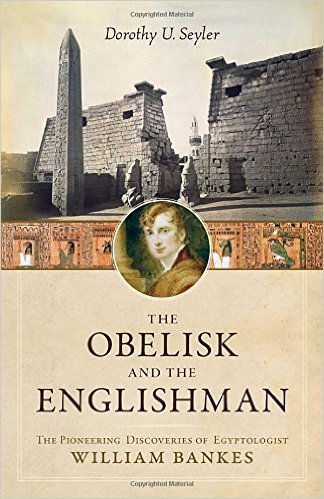

The Obelisk and the Englishman: The Pioneering Discoveries of Egyptologist William Bankes

The Obelisk and the Englishman: The Pioneering Discoveries of Egyptologist William Bankes

by Dorothy U. Seyler

Prometheus Books. 304 pages, $26.

BY THE TIME I finished this book I had come to the conclusion that the subtitle was somewhat misleading. The middle— and largest—section does describe William Bankes’ 1815–20 travels through Egypt and the Middle East. There, often battling severe illness, recalcitrant administrators, and hostile locals, this scion of English landed gentry, who had been expected to do nothing more adventurous than spend his adult years sitting in Parliament and whose adolescence had been largely frivolous, showed an amazing amount of grit and downright courage in his efforts to uncover and record some remarkable historical sites. The question is, are Bankes’ discoveries in Egypt really the main subject of this book?

William John Bankes (1786–1855) was one of the first modern Westerners to see and, more importantly, record in accurate detail the carved city of Petra and the interior of the newly excavated temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel. (Seyler uses the spelling “Ramesses,” which may be phonetically closer to the Egyptian original but obscures the association with the old Ramses condoms.)

If Bankes is virtually unknown today despite this pioneering work, it is because, while he showed amazing perseverance in discovering and recording such sites, he evinced no interest in publishing his findings once he returned to England. Fortunately, he was generous about sharing his discoveries with scholars who were able to use his work to further their own research in Egyptology. Seyler argues that some of the material Bankes furnished Thomas Young, such as the list of pharaohs he discovered at Abydos and his work on hieroglyphs, aided Young in deciphering the Egyptian holy script—work which the French Champollion evidently used in turn without crediting either Englishman.

The problem for me in this central part of the book is that it is a narrative of events without feelings. Bankes was good about recording his discoveries but did not bother to note his reactions to them or the events that led up to them. This isn’t Seyler’s fault, certainly, but it leaves us looking on from a distance at a man who braves sometimes astounding obstacles without telling us why. Imagine reading a summary of the plot of Raiders of the Lost Ark with illustrations but no dialogue or soundtrack.

The first and last sections of the book are more frustrating still. In the first seventy pages, Seyler recounts Bankes’ youth and time at Cambridge, where he was a friend of Lord Byron and others who dared to go beyond the bounds of England’s restrictive moral code. Here the problem is that there are almost no documents of any sort. Seyler does a lot of supposing and proposing, in particular about Bankes’ involvement in possible same-sex activity, perhaps even with Byron, but it’s all speculation. She recounts the sad outcome of the Vere Street roundup in 1810, for example, as a result of which about twenty men were accused of sodomy and subsequently hanged. But when she then adds “although the record is silent, William’s internal anguish must have been severe,” she has nothing to support such speculation or convince us that Bankes reacted in this way.

The last seventy pages of this book suffer from the same problem. Bankes is twice arrested for homosexual activity after his return to England, in 1833 and 1841. The first time he’s able to buy his way out of prosecution, helped by the fact that he knew some very influential people, such as the Duke of Wellington, who were willing to testify to his “manliness.” This was evidently proof enough that Bankes could not have committed a homosexual act (which by the way suggests that, well before the date proposed by Foucault, early 19th-century England had a sense of a distinct homosexual personality). The second time, however, he didn’t have such character witnesses, and the evidence was harder to dismiss. His lawyer advised Bankes to flee England for France at once and, like Wilde and other Englishmen in that situation before and after, he did so. Though he seems to have been able to manage a few short, clandestine trips back home, Bankes spent the last decade of his life in France and then Italy. Again, however, there are no documents that tell us how he felt about all this, much less a work of art like Wilde’s Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Seyler can’t be expected to fabricate what doesn’t exist, of course. What might have compensated for this absence, however, is more socio-historical context. She quotes Bankes’ lawyer as saying that the Home Office didn’t seem willing to let Bankes off easily in the second case because it felt “a desire to respond to ‘public clamor for the sake of gaining a title to a little short lived popularity among the lower grade of society by affecting to deal an equal justice to the great and the little.’” Was there popular reaction to the English government’s increased prosecution of men for homosexual activity, reaction that accused the Home Office of classism and selectivity? How was this second case presented in the press of the time?

Such pressure from the working class could not have been too great. Once Bankes left England, the Home Office did nothing to pursue his case. Bankes spent the last fourteen years of his life arranging, long-distance, for lavish improvements on his house in Dorset, which included the purchase of a great deal of mostly Spanish and Italian art. Whether it was realistic or not, he must have thought that he would eventually be able to return home to enjoy it.

William Bankes’ story is worth telling, at least parts of it. If I had been Seyler’s editor, I would have suggested that she greatly reduce the first section and in general spend less time speculating about things for which, unfortunately, she had no documentation. On the other hand, I would have asked for more context in several fields. It would have been good to hear from some modern Egyptologists to get a sense of the value of Bankes’ discoveries and drawings to other Egyptologists. It would also have been good to hear from modern art historians about the role, if any, that Bankes’ art collecting played in the way English taste in Renaissance Spanish and Italian art has developed in the last two centuries. And, as I’ve mentioned, it would be interesting to know what if any role Bankes’ second arrest for homosexual activity had in the history of thought about homosexuality in England in the 19th century leading up to the trial of Oscar Wilde. The answers to those questions would determine what was really important about William Bankes and how the subtitle of the book might better have been phrased.

Richard M. Berrong, professor of French literature at Kent State University, is the author of In Love with a Handsome Sailor.