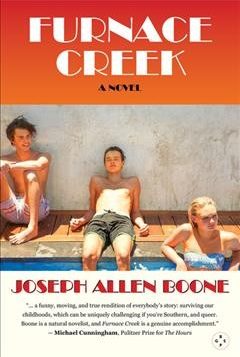

FURNACE CREEK: A Novel

FURNACE CREEK: A Novel

by Joseph Allen Boone

Eyewear publishing. 372 pages, $26.

JOSEPH ALLEN BOONE’S debut novel, Furnace Creek, is a contemporary queering of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations in which the author transposes key elements of the classic narrative to 20th-century America, centering the story upon a gay stand-in for the more conventional Pip. Boone, a professor of English and gender studies at USC, clearly knows whereof he speaks. In such scholarly works as Tradition Counter Tradition, Libidinal Currents and The Homoerotics of Orientalism, Boone displays a wide-ranging knowledge of the novel and how it reflects—and sometimes influences—social codes around gender and sexuality.

Furnace Creek opens in the 1960s when its protagonist and narrator, Newt Seward, is a teenager living a fairly sheltered life in Virginia. We first meet Newt when he’s lying beside the eponymous creek satisfying himself (as adolescent boys free of Victorian literary constraints are wont to do) and is suddenly confronted by Zithra Jackson, a former maid and recently escaped convict who blackmails him into aiding her flight.

Furnace Creek, it turns out, is named for a stone oven where Confederate bullets were forged. Boone thus turns the reader’s attention to a distinctly American history, further elucidated by the fact that Zithra, a stand-in for Dickens’ Magwitch, is a Black woman, her fate part and parcel of the Southern legacy and America’s original sin. Already we see the makings of a parallel to Dickens’ conflict—one based more on race than on class.

Furthering the Dickensian parallel, soon after his initial trauma, Newt begins working for an eccentric bachelor named Mr. Julian, who wants someone to organize the extensive library in his mansion. Mr. Julian’s closeted behavior makes for a delicious parallel to Dickens’ Miss Havisham, though his surroundings are far more fastidious (no moldering wedding cakes) and his worldview a bit less tragic.

When Newt meets Mr. Julian’s twin wards, Mary Jo and Marky, who are visiting from Europe, the plot gets much more complicated. Newt, still puzzled about his sexuality, finds himself drawn to both of his new friends, who play upon his innocence throughout the novel with a disturbing blend of allegiance and manipulation. Seduced by their world, Newt grows ever more determined to escape the confines of his own. His wish is granted when a mysterious benefactor comes to the rescue, paying for his education and entrée into distinguished circles. Soon Newt enrolls at the thinly disguised “Phipps Andover” and eventually at Harvard—right at the height of student protests over the Vietnam War. In the Bildungsroman tradition, the novel culminates in Newt finding his independence and finally resolving his sense of self—and his sexuality.

Like other writers who update and/or “queer” a classic text—a good example would be Michael Cunningham in The Hours—Boone picks and chooses from his source material in order to make the story believable in a contemporary context. While the parallels to Great Expectations are clear, the plot veers off in satisfying ways—most notably, its injection of sexual elements. Adherence to the original story, however, does have its downside. At times its faithfulness to Dickens seems to drive the plot rather than simply complement it. Like Dickens, Boone treats the identity of his hero’s benefactor as a mystery and an important plot point. But anyone familiar with Great Expectations knows exactly how this crucial piece of the story will play out. One might wish for a more ironic stance in relation to the original novel, some amusing acknowledgment, perhaps, of what Harold Bloom called “the anxiety of influence.”

In its resetting of Dickens, Furnace Creek reads like an entertaining amalgam of the Victorian tradition and Southern Gothic. Newt’s first-person narration is littered with Britishisms (“hob,” “two weeks’ time”) and often carries the highfalutin syntax of social aspiration, but the legacy of the South is never far away, as Zithra’s story brings on the climax and thus frames the narrative.

As any English major knows, the love of literature hinges not just on beautiful writing but on an awareness that the stories of the past have a lot to teach us about the present. By transporting Dickens into our own era, Boone demonstrates just that—and also shows that those stories belong to all of us regardless of our gender, sexuality, or time in history.

____________________________________________________

Lewis DeSimone’s latest novel, an homage to E.M. Forster, is titled Channeling Morgan.