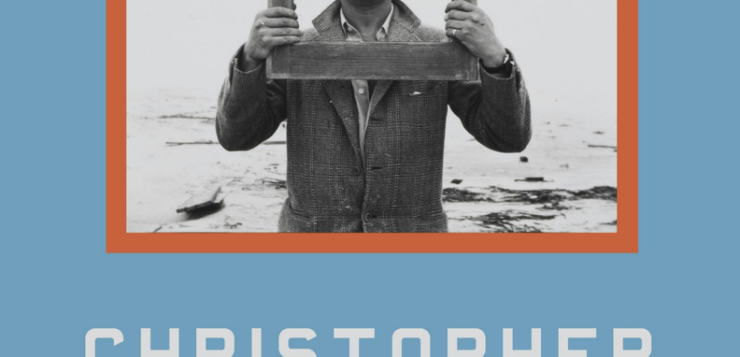

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD

INSIDE OUT

by Katherine Bucknell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

864 pages, $45.

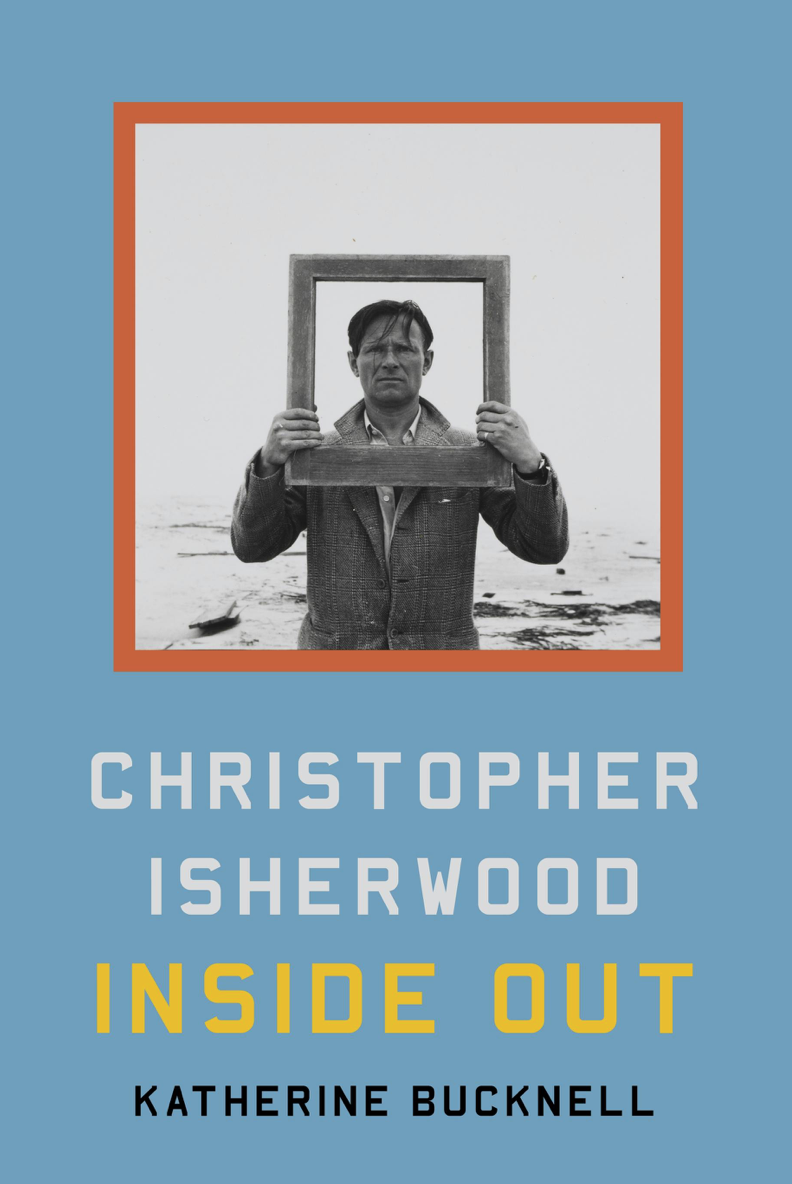

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD was born 120 years ago on his family’s estate in northern England, but the life he lived and the books he wrote speak with a powerful voice to the experience of queer people in 21st-century America. His life story is all about the need to be one’s authentic self and to resist forces that would deny that need, and it is told with impressive skill by Katherine Bucknell in her major new biography, Christopher Isherwood Inside Out.

Isherwood’s early life resembles a Masterpiece Theatre period drama. He was raised with a nanny and sent to boarding schools. His father, a colonel in the British army, was killed early in World War I. His doting mother, sensitive to class distinctions and devoted to the Church of England, hoped her son would marry and have an academic career after he completed studies at Cambridge. However, early on Isherwood rebelled against the world into which he was born. After two years at Cambridge, where he spent most of his time writing stories, he deliberately failed his exams and withdrew. His first novel, All the Conspirators, was published in 1928, when he was 24. The next year, he left England for Berlin, where

The young Isherwood took on what he would later refer to as the “Others”: the British Empire, Cambridge, Anglicanism, social class, marriage, sex roles. The hidden source of his rebellion was his homosexuality. Under the tutelage of his friend W. H. Auden, Isherwood embraced his sexuality in Berlin, where he had a series of affairs with young, working-class men. This was his first pivot toward authenticity. The next would come in 1939, when he and Auden left England for America on the eve of World War II. By then Isherwood was a pacifist. His first great love, a young man named Heinze, was now a soldier in the German army, and Isherwood knew he could never take up arms against him or any other man. Once the war began, he and Auden were widely denounced in England for abandoning their country.

There would be two more pivots. Five months after arriving in New York, Isherwood set out for California, where he would support himself by writing for movie studios. In Hollywood, English friends introduced Isherwood, who considered himself an atheist, to Swami Prabhavananda, a Hindu monk who ran the Vedanta Society of Southern California. Becoming an acolyte of the Swami’s teachings, Isherwood would follow a lifelong quest involving meditation and spiritual discipline to help him see beyond the illusion of this world and find enlightenment about life’s ultimate meaning. Through Swami, both his guru and a father figure, Isherwood came to believe in his inherent worthiness as a gay man. Many fellow writers and reviewers of his books were either skeptical of his embrace of Vedanta or never understood it.

The final, most important pivot came in 1953, when he began a relationship with Don Bachardy, an eighteen-year-old college student thirty years his junior. While the relationship lasted until Isherwood’s death, it was fraught with conflict stemming from their age difference, Isherwood’s growing celebrity, Bachardy’s struggle to establish his career as an artist, and the many sexual liaisons that both had with other men. They found ways to express their love through the home they created together in Santa Monica and their collaboration in each other’s work.

Before emigrating to America, Isherwood published several books based on his circle of English friends in which there are clear suggestions of homosexuality. But the two short novels that made him famous, Mr. Norris Changes Trains and Goodbye to Berlin, were set in Berlin and derived from diaries that he kept of his daily—and nightly—life in the German capital. Published in the U.S. as The Berlin Stories, they are the source of the 1951 play I Am a Camera and the 1966 musical Cabaret. Isherwood was not involved in either adaptation, but the royalties he received from the musical and later the movie made him financially secure. In the Berlin novels, he made himself a character, an observing narrator who reveals little about himself, a “camera” recording the Nazis’ rise to power and the people, including homosexuals, who were caught up in the cataclysm that would soon engulf them. Isherwood’s appearance in his own books became his trademark and was key to his search for authenticity as a writer.

Once in America, he again began keeping copious diaries, filled with touching self-examination, that he later mined for a steady output of novels, memoirs, and biographies. His books received mixed reviews and were never bestsellers. In 1964, he published a landmark in gay literature, A Single Man. The novel, about one day in the life of George, a closeted college professor whose lover has died in a car accident, stemmed from his experiences teaching at Los Angeles area colleges and his ever-present fear that he might lose Bachardy. It is notable for the open rage that George expresses against the heterosexual world, and also for a beautiful metaphorical passage near the end of the book in which tide pools washed over by ocean waves represent individual identity subsumed into a larger consciousness. Indirectly, Isherwood revealed here both his sexuality and his spirituality. The novel received mixed (or negative) reviews in 1964, but he never doubted its worth, and it has since become a classic of gay literature.

In 1971, Isherwood came out in print for the first time, writing candidly about his homosexuality, tellingly enough, in a biography of his parents titled Kathleen and Frank. The death of W. H. Auden in 1973 prompted him to revisit his years in Berlin and write a memoir of that period in which he would make himself the central character, not just an observer, and be open about his sexuality. Christopher and His Kind, published in 1976, made Isherwood a celebrity in the increasingly visible gay community. As he said in his public talks, he had “found his tribe.” Despite many negative reviews, the book sold well.

Katherine Bucknell was well positioned to write this new biography, having edited four large volumes of Isherwood’s diaries. She had access to the enormous archive of written material about Isherwood, and she interviewed both Don Bachardy—who still lives in the house they shared—and many people they knew. The result is a detailed life story and a brilliant critical study of the author’s books. Bucknell is adept at showing the origin of the books in the events of Isherwood’s life, particularly childhood experiences that stayed with him forever. This is a deeply penetrating psychological study written in direct, lucid, and graceful prose worthy of its subject.

Bucknell takes us on a long journey that ends on an emotionally shattering note. In 1986, when Isherwood lay dying in his bed at home, Bachardy cared for him and drew a new portrait of him every day, creating a diary of physical ruin. The writing had come to an end, but Bachardy’s chronicle continued until Isherwood’s Atman, his soul, was released from his body.

Daniel A. Burr, a frequent contributor to this magazine, lives in Covington, Kentucky.