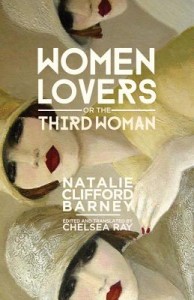

Women Lovers, or The Third Woman

Women Lovers, or The Third Woman

by Natalie Clifford Barney

Edited and translated by Chelsea Ray

Wisconsin. 216 pages, $29.95

“THEY LOOK GOOD together … seeing them makes even people hur-rying to catch the train turn around and do a double take. They are a good-looking—and modern—couple.” So wrote Natalie Clifford Barney, with aching fragility and resignation, of two women she had loved and lost to each other. The two were Liane de Pougy and Mimi Franchetti. At different stages of Barney’s life, she’d been passionately in love with each woman, and both had broken her heart—one leaving a well-healed scar, the other a still-fresh wound. As the painful scene continues, she follows close behind, acutely aware of her own insecurities, watching with eyes that “carry with them the discomfort of their own sincerity.”

In this autobiographical modernist novel, Women Lovers, or The Third Woman, written in 1926 as Amants féminins ou la troisième, Barney constructed a barely fictionalized memoir of passion, jealousy, and heartbreak. It’s important to note that she never embraced the concept of monogamy, loathed possessiveness in others, and once seemed so indomitable that French poet Rémy de Gourmont dubbed her “the Amazon.” Now, at fifty, she found herself cast aside in a love triangle as “the other woman.” Heartbroken, tortured by jealousy, and feeling resentment over being a conduit for two women she considered her own, she put pen to paper, designating Liane simply as “L,” Mimi as “M.” and herself as “N.”

A fabulously wealthy American expatriate who lived in Paris, Barney is perhaps better remembered as a witty saloneuse, an arts patron, and a seducer of women than as a writer. Yet she was a writer, and a prolific one. Her first book, a daring collection of overtly lesbian poems called Quelques Portraits: Sonnets de Femmes, came out in early 1900 when she was 23. The book received little fanfare in France but caused big trouble for her back home. When the family’s good name appeared in scandal sheets under such headlines as “Sappho Sings in Washington,” her social-climbing father set out to destroy nearly every copy in existence. After his death two years later, she got a sizable inheritance and won the freedom to live and create as she pleased. Her literary output consists mainly of poetry, plays, epigrams, and memoirs, written almost exclusively in French. During her lifetime, she published one novel, The One Who is Legion, or A.D.’s After-Life (1930), which is also her only work written in English.

At her Left Bank home, she hosted one of the most famous and enduring salons of the 20th century. A complete list of her guests would include virtually every major artist and writer who passed through Paris from 1909 through the late 1960s. The salon’s notoriety tended to overshadow her own talent as a writer. For that reason—among others, which Melanie C. Hawthorne discusses in her brilliant introduction to Women Lovers—Barney has been undervalued as a modernist literary figure in her own right. But thanks to Chelsea Ray’s research and meticulous translation, Barney’s experimental modernist novel is available for the first time in English, further advancing her literary legacy.

With Barney displaced as the third woman, who were the other two women? Once a dancer at the Folies Bergère, Liane de Pougy was a Belle Époque courtesan with celebrity status who wrote fascinating accounts of her life as a demimondaine. Her memoir My Blue Notebooks provides insight into her relationship with Barney over the years as well as real-life episodes the latter recounts in Women Lovers. As for the love triangle? “It was [Natalie] herself who prepared her own fate,” Pougy tells us.

Those two went way back. Barney’s romantic involvement with Pougy began in 1899, when both were young, wild, and the toast of Paris. Pougy dished many of those salacious details in her novel Idylle Saphique. While their initial relationship didn’t last, they remained close friends and rekindled their sexual intimacy in later years despite Barney’s other relationships and Pougy’s marriage. By the mid-1920s, jealousy, bitchy brink-manship, and triangular tensions between them had already emerged. For example, in 1922 Pougy became obsessed with Barney’s longtime lover, Élisabeth (Lily) de Gramont. In that situation, Pougy retreated as the odd one out while Barney retained control of her position. But the next time around, things didn’t pan out the same way.

In 1926, Barney’s new lover was Mimi Franchetti, an Italian-Jewish aristocrat. She wasn’t a writer; instead, she was written about. Her personal charisma would prove a compelling literary subject for both Barney and Pougy. Born into immense wealth, Franchetti grew up in Venice as the granddaughter of a Rothschild and the daughter of an opera composer. For about a year, she and Barney had been involved in an intense love affair when Pougy resurfaced, which led to unexpected consequences.

In Women Lovers, Barney writes explicitly and unflinchingly about sex (really hot sex) and gender role-play between women, which was extremely courageous for the period. As her biographer Suzanne Rodriguez observes, this kind of unabashed honesty about lesbian sexuality was shocking back then. When writing of her own vulnerability in love, however, Barney exposes an utterly different side of her character: a woman who is wanting, woeful, and wounded—far from the mythical Amazon persona.

Whether she ever intended to publish this novel is unclear; it can be argued that she wrote it primarily for herself. She once quipped that she wanted to be the bow, the arrow, and the target. Perhaps the writing served as a cathartic experience, allowing her to conduct a post-mortem, to retrieve memories of lost love, to embrace her own fragility, and to explore her pain a little more deeply.

Shannon Leigh O’Neil is a writer and researcher in New York City and the former managing editor of GO! magazine.