The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard

The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard

Edited by Ron Padgett

Library of America. 541 pages, $35.

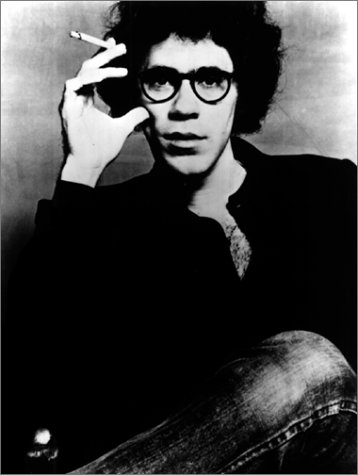

JOE BRAINARD (1942–1994) is a name that doesn’t appear in comprehensive reference books on gay American writers and artists, though his accomplishments included drawing, poetry, prose, theatre design, and more. The omission makes this beautifully realized compilation of Brainard’s writings an essential work for anyone interested in mid-century gay life and culture.

One of four siblings, all of whom ended up artists or working in the arts, Joe Brainard was raised in Tulsa and moved to New York at age nineteen (after a brief sojourn at the Dayton, Ohio, Art Institute), where he immediately took up with the New York School of Poets, whose members included Anne Waldman, John Ashbery, James Schuyler, Frank O’Hara, and Ron Padgett, among others. Brainard and Padgett, who had been friends since childhood, had started a small magazine called the White Dove Review while still in high school. It ran for five issues and featured such writers as Robert Creeley, LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), and Ted Berrigan. While in his twenties and finding it hard to make a living from his art, he began an open relationship with well-off poet Kenward Elmslie, whose many books of poetry he illustrated with drawings ranging from crushed cigarettes to flowers and fruit and the occasional male nude. Wrote Brainard in 1971: “Kenward’s money. I like it too much. And have gotten to need it too much. And am still embarrassed to admit to taking it.” Elmslie had a summer house in Calais, Maine, where Brainard retreated every summer.

Reprinted in its entirety in Collected Writings is Brainard’s 150-page I Remember, composed between 1969 and 1973. First published by Full Court Press in 1975 and reprinted in 1995 by Penguin, this is a memoir recounted in sentence-length fragments and short paragraphs. Not strictly chronological, the phrases nevertheless build on each other. Here, he reflects on the first time he met Frank O’Hara: “[H]e was wearing only a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up to his elbows. And blue jeans. And moccasins. I remember that he seemed very sissy to me. Very theatrical. Decadent. I remember that I liked him instantly.” For his part, O’Hara wrote in a letter to artist Larry Rivers: “Now I am making some cartoons with Joe Brainard, a 21-year-old assemblagist genius.” (Brainard’s first solo exhibition, in 1964, occurred right after being chosen by Larry Rivers for a group show.)

Other memories in I Remember may strike a chord with many readers: the “algebra teacher who very generously passed me”; classrooms with “roll-down maps and rubber-tipped wooden stick pointers”; “bar stools and kitchen nooks and brass ivy planters”; “losing things through a hole in your pocket.” A rather particular memory was “when a fish-tail dress I designed was published in ‘Katy Keene’ comic” (a 1950’s cartoon strip appearing in his local newspaper). In his article “Saint Joe” (Art in America, July, 1997), Edmund White mentioned Kenneth Koch (another member of the New York School) using I Remember to teach poetry—a technique adopted by other teachers: use the words “I remember” to begin a short paragraph, and then recall very personal memories, related sets of memories, and so on.

Most of the essays in Collected Writings are either autobiographical or commentaries upon contemporary life, with such titles as “Queer Bars” and “The Gay Way.” “Andy Warhol: Andy Do It” (1963) can be read on the surface as great praise, but right below is a subtle slam: “I find Andy Warhol to be spectacular, grand, clean, courageous, great to look at, and likable. I like Andy Warhol. And there is more to be said. I like Andy Warhol.” An entry from his 1972 Washington, D.C., journal found him regretting his own “lack of focus” and “lack of dedication” as a painter. “Although I work all the time, do I really work that hard?” He was also designing book covers, theatrical sets, and costumes.

In an excerpt from his “1969 Diary,” he wrote that he liked the cartoon form, the combination of words and pictures, both admitting and boasting that “there is always something slightly unprofessional about my graphic work. Which is probably the best thing about it.” Scattered throughout Collected Writings are reproductions of some of his drawings, including a few of the less salacious “Nancy” cartoons, based on the Ernie Bushmiller comic, which started in the 1930’s. (For the salacious ones, consult Siglio Press’s 2008 The Nancy Book, which also includes an essay by Ron Padgett.)

This reviewer had the opportunity to see a small but charming exhibit of Brainard’s works at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York earlier this year, mounted to coincide with the publication of Collected Writings. The two-dozen framed collages, many of which were trompe l’oeil, were filled with vibrant colors and non-ironic themes of homey kitchens, playing cards, fruit, and flowers. There was also the occasional male torso peeking out from a mid-Victorian greeting card, with its pink ribbon and glitter still intact.

In 1978, Brainard stopped writing, stopped exhibiting his work, and devoted his life to his many friends and to reading. (He’d read avidly all his life: Gertrude Stein, Evelyn Waugh, James Purdy, Jean Genet, Lillian Hellman. Biographies were his favorite.) The reasons for this early retirement are unknown. In Paul Auster’s introduction to Collected Writings, he noted the possibility of burnout (Brainard had done speed for years); feelings of failure as an artist; distress over the commercialization of the art world. In an excerpt from his “1969 Diary” he wrote: “I imagine that I will die young: 40 or 50. Not because I want to die young. But because I can’t imagine being old.” Joe Brainard was lost to complications of AIDS at age 52.

Martha E. Stone, literary editor for this magazine, is a research librarian at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.