Translated by Mark Oshima

What follows is the first English translation of a piece by the great Japanese novelist, poet, and playwright Yukio Mishima (1925–1970), which appeared in the September 1966 issue of Higeki Kigeki(“Tragedy and Comedy”).

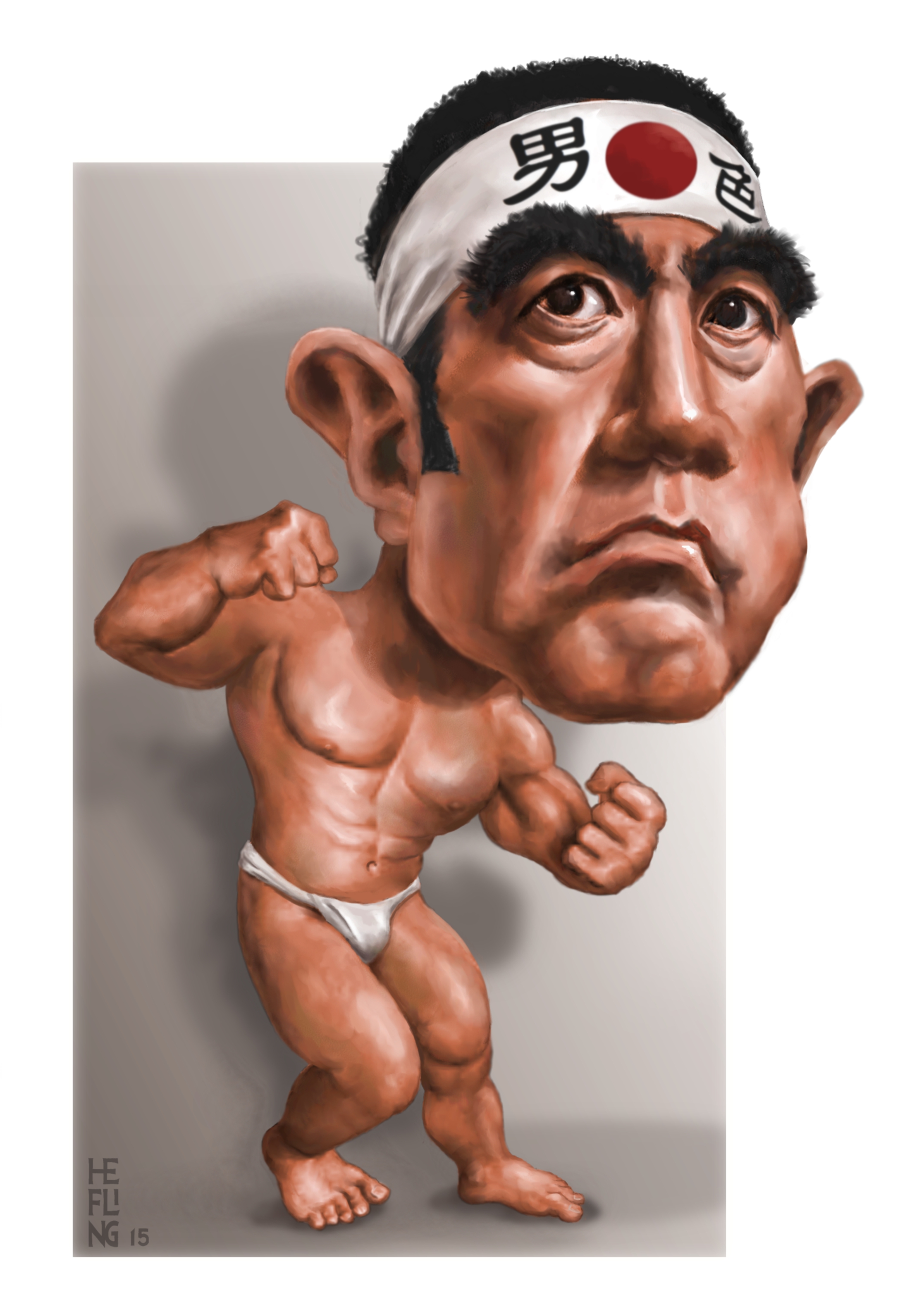

AS YOU CAN SEE from his photograph, Tennessee Williams looks like a Southerner, an ordinary-looking, slightly plump man with a short mustache. From the eccentric nature of his works, you might imagine a pale and skinny, high-strung man, but he doesn’t look anything like that. He looks perfectly ordinary and he speaks with a Southern drawl. He seems for all the world like nothing but the owner of a small plantation by the Mississippi River.

But still, there is no doubt that he is a great playwright, a great artist. But unlike the image of the artist in Japan, in America there is a bit of a romantic nuance. The artist is imagined as being uncontrolled and selfish, capricious and eccentric, highly individualistic, demanding and difficult to deal with. The American writer is not a part of larger organizations of writers, as in Europe, and all business matters are left to their agents. So, in America, since writers can make a living working in a solitary state, that is why this romantic image still remains. Tennessee Williams is indeed this kind of romantic figure. It is not accidental that he was extremely attracted to novels by Dazai Osamu like The Setting Sun and No Longer Human in English translation. Dazai was a wild child of a good family in the Tohoku region of Japan. Dazai’s decadence and desire to recover himself probably seemed to Tennessee Williams, born in the American South, as a portrait of himself.

But for a variety of reasons, it is not very good for a playwright to like Dazai. The weakness of the architecture of Tennessee’s plays and their hysterical impressionism is reminiscent of Dazai. It was not so bad once Dazai was dead, but while he was alive, he was always opening up his wounds and showing them off and using this to condemn the hypocrisy of others. That is like trying to be an austere Indian ascetic in the middle of material civilization. Tennessee was probably most successful with this approach in A Streetcar Named Desire. It was outstanding for its sense of the lyricism of isolation, its purity and self-mockery. Blanche comes to symbolize the South in a way that is approached by none of the other characters in the play.

But for a variety of reasons, it is not very good for a playwright to like Dazai. The weakness of the architecture of Tennessee’s plays and their hysterical impressionism is reminiscent of Dazai. It was not so bad once Dazai was dead, but while he was alive, he was always opening up his wounds and showing them off and using this to condemn the hypocrisy of others. That is like trying to be an austere Indian ascetic in the middle of material civilization. Tennessee was probably most successful with this approach in A Streetcar Named Desire. It was outstanding for its sense of the lyricism of isolation, its purity and self-mockery. Blanche comes to symbolize the South in a way that is approached by none of the other characters in the play.

Tennessee writes every morning.

He gets up early and faces his desk for at least five hours every day. He quits around lunch time. But even so, he always complains that he can only write a line or two. I always believed that a play comes out of its structure, so that if you have the structure right, you should be able to write the whole thing at one go, so I couldn’t understand Tennessee’s way of working at all. Why on earth does Tennessee take so much time to write? No matter how vital each and every line is, if you only write one or two lines a day, you would completely lose the flow. That’s ridiculous! I thought that by taking a whole year to write a play, Tennessee was writing a play as if writing a novel.

When he finishes writing for the day, Tennessee goes for a swim. Even when he came to Tokyo, despite the fact that it was September and there were many chilly days, he immediately moved from the Imperial Hotel because it didn’t have a pool and stayed at the Akasaka Prince Hotel. There, even though there weren’t many people because it was autumn, he happily went swimming daily.

At that time Tennessee had a faithful secretary named Frank Merlo who had been with him for over ten years. The way the world works can be funny. Often when you actually meet a very talented and famous person, it can turn out that he seems very ordinary. But by his side and in his shadow, there is someone very individual with an overwhelming personality. There are probably all kinds of reasons for this. A writer’s individuality is almost totally expended in his works. But with him is a person who has accepted the idea that the most important thing is to express yourself, but without his own works in which to express this individuality, he inevitably comes to seem much more colorful than the writer himself. Frank was not particularly a genius or extraordinary person and was just a typical Italian: chatty, cheerful, and friendly. He was a sharp businessman and thought about everything in a practical way. He was the perfect secretary to compensate for the weaknesses in the romantic Tennessee.

But whether he was an ideal secretary in the usual sense of the word is a little doubtful. Once I visited Tennessee in New York at the hotel that he was using as his work space. The room was crammed with five cats, three dogs, a parrot, and several other animals that I couldn’t identify. The room stank and was filled with the cries of all these animals. But I learned that they were not Tennessee’s pets; they all belonged to his secretary Frank, and every time they went to New York from his home in Key West, they took the entire army of animals with them. Tennessee had a small workroom in the back that was relentlessly assailed by the noise and smell. Tennessee complained, as always, “I can’t write, I can’t write!”

But while still in his thirties [Merlo actually died at age 41], Frank died of cancer. Even though it seems that they had all kinds of fights while he was alive, when Frank died, it was a great blow to Tennessee. Not knowing what I could do to comfort Tennessee, I wrote him a long letter mourning Frank.

Usually when Tennessee had a hit play, he’d stay in New York for a long time in a hotel room costing over a hundred dollars a day. But his plays were not always hits.

Once I went to the opening of a rare comedy by Tennessee Williams, Period of Adjustment. Strictly speaking, I didn’t actually see the opening. After my plane landed in New York, I went to my hotel to change, and by the time I got to the theater, the play had just ended. I had no intention of attending a black-tie gala while traveling. So I ventured backstage and saw an exhausted-looking Tennessee sitting in his tuxedo in the darkness by the stage sets talking to his agent. His eyes were puffy and swollen—of course, his eyes were always a little puffy—and seeing Tennessee looking like that, I decided not to bother him.

One week later, Tennessee invited me to a Chinese restaurant. Period of Adjustment was not a hit either critically or commercially.

All through lunch, with a dejected face, Tennessee continually talked about the failure of this play. All the newspapers had praised it except for The New York Times. “I missed The New York Times!” Tennessee had all kinds of disappointments and was going to go back to Florida that night.

I could see before my eyes that the bitterness of the theater had filled his heart. I too am something of a playwright. With every play, there is a tremendous sweetness that attracts people—this draws the playwright, this draws the director and the actors, this draws the audience. This sweetness fades and vanishes easily. But the bitterness never goes away and accumulates inside of you. And that ash-colored accumulation becomes the motivation for writing the next play. No matter how it works out, playwriting is a rotten business.

Tennessee and I shared the same agent.

“Have you seen Tennessee?”

“No.”

“I don’t meet with him either, but I talk with him on the phone. Come to think of it, I haven’t actually seen him in a long time.”

For my part, I didn’t have the curiosity that I had when I was younger, and I no longer wanted to go and meet famous people. Tennessee always seemed so busy and reclusive and there was no point in chasing him down and demanding to meet.

“When are you leaving New York?”

“Tomorrow.”

“Then write a letter to Tennessee before you go. Just a couple of lines will be enough.”

“Can’t I call?”

“No, don’t call. You should absolutely not call. Write a letter, this is what you should write, ‘I’m just leaving New York. I’m sorry that we didn’t have a chance to get together. You are always in my thoughts. Be well.’ That’s all you have to write.”

I did exactly as I was told. This was a fine way of doing things. For both of us, it was better not meeting. This didn’t take time or excessive emotional investment, but still for a moment, it could rescue Tennessee from his isolation and solitude. “Just drop a line.” This is like a drop of rain from the heart of one human being to another. I think this is a good example that shows how much American agents use psychology with their clients, and also how good they are at it.

Mark Oshima is a kabuki scholar and translator based in Tokyo. His translations include Mishima’s Black Lizard, which will have a staged reading at the Tennessee Williams Festival in Provincetown in Sept. 2019.