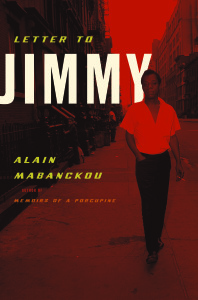

Letter to Jimmy

Letter to Jimmy

by Alain Mabanckou

Soft Skull Press. 176 pages, $15.

THIS SHORT BOOK provides many insights into the life and work of James Baldwin (1924-1987). On the twentieth anniversary of his death, French-African writer Alain Mabanckou has written a biography in the form of a letter to Baldwin, addressing the novelist as a way of examining his life and writings as he considers Baldwin’s relevance today. Mabanckou finds much in Baldwin that still speaks to us concerning race, sexuality, and Western history.

Mabanckou begins by thinking about a wanderer he observed while living in Los Angeles who turned out to have a connection of sorts to Ralph Ellison. His reflections on this stranger lead him to reminisce about Baldwin, who wandered as well, both physically and emotionally, moving from Harlem to Greenwich Village and on to Paris, always isolated from his surroundings by virtue of being “black, bastard, gay and a writer.” He used his outsider perspective to create powerful works that still resonate today, notably the novels Giovanni’s Room and Go Tell it on the Mountain and the essays “The Fire Next Time” and “Everybody’s Protest Novel.”

Born to an unwed mother in 1924, Baldwin grew up in a dysfunctional family in Harlem during a harsh period in U.S. history. Not only did he grow up in a black ghetto where the police eagerly enforced racial discrimination; he also had to deal with a stepfather who was “consumed by his religious faith.” David Baldwin passionately hated white people, refusing to let his son’s teacher take him to the theater. He also seemed to hate his own and his son’s blackness, as he made many comments to his young son about the boy’s ugliness and “big eyes.” For all his work as a preacher and his commitment to Christian doctrine, he could not find peace for himself. Indeed, “convinced that his own family [was]plotting to poison him,” he refused to eat at home and later died from tuberculosis. Of the latter event James Baldwin remarked: “the disease of his mind helped the disease of his body to destroy him.”

Despite his relationship with his father, Baldwin didn’t change his name. As Mabanckou observes, in an age when many African Americans, such as Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali, did just that, Baldwin kept his name as a reminder of “a lineage forged of lurid relationships, domination, whipping, and slavery.”

Baldwin’s friendship with novelist Richard Wright was equally complicated. Having followed the author of Native Son to Paris, Baldwin would later reject his mentor’s work. In the essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel” he argues that Native Son, like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, favors “moral stories over art,” displaying insincere outrage over big issues and showing off the authors’ emotions. Although Uncle Tom’s Cabin moved him as a child, as an adult he finds it dishonest, sentimental, and unable to elicit true feelings. He levels the same criticisms at Native Son, finding the characters “to be far removed from the truth of daily life.” This inevitably caused a rift between Wright and Baldwin, but it did establish Baldwin as a “young Turk.”

Mabanckou also considers Baldwin’s life as an expatriate. While in France he generally escaped the racism that dogged him in the U.S. To be sure, at first he was isolated from French society due to the language barrier, spending time instead with white Americans also visiting and living in France. Even abroad he was not exempt from prejudice. Renting a room in a farmhouse in the countryside, he had to win over his landlady, a woman who had lived in Algeria during colonial times and “always believed that black people had helped chase the French out of … her homeland.” Nevertheless, living abroad gave Baldwin the opportunity to discover himself and shape his talent. Deeply intimate, Letter to Jimmy is a tribute from one expatriate writer to another who achieved his dream of becoming “an honest man and a good writer.”

________________________________________________________

Charles Green is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.