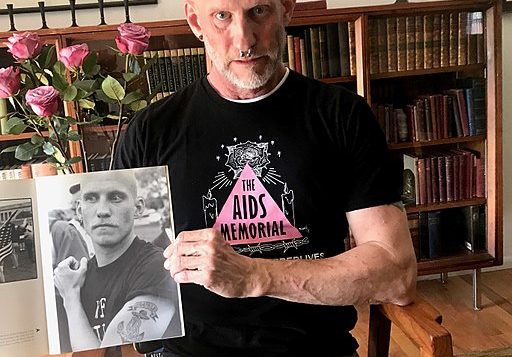

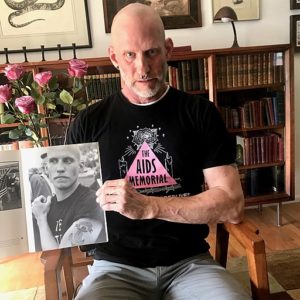

BORN IN 1962, Malcom Gregory Scott, is an American writer, activist, and AIDS survivor. As a young man he joined the U.S. Navy, but in 1987 he was discharged for homosexuality. Upon his release, Scott also learned that he tested positive for HIV. A decade later, his battle with AIDS nearly ended his life. Miraculously, with the emergence of protease inhibitors coupled with medical marijuana, he survived, and he survives today.

In the years that followed his discharge from the military, Scott dedicated his life to activist efforts that included legal challenges to the Department of Defense for anti-gay discrimination, support for medical cannabis, and advocacy work for organizations such as ACT UP and Queer Nation. Through TV appearances, speeches at huge rallies and small workshops, organizing protests, guerilla tactics, you name it, Scott became one of the most effective LGBT activists of the 1990s.

In the years that followed his discharge from the military, Scott dedicated his life to activist efforts that included legal challenges to the Department of Defense for anti-gay discrimination, support for medical cannabis, and advocacy work for organizations such as ACT UP and Queer Nation. Through TV appearances, speeches at huge rallies and small workshops, organizing protests, guerilla tactics, you name it, Scott became one of the most effective LGBT activists of the 1990s.

As we find ourselves in politically and socially perilous times, I interviewed Scott via e-mail relay. In what follows he reflects on his life and work, shares the story of his near-death episode, and offers his take on what today’s activists need to do to succeed in advancing the cause of LGBT rights.

A. Miller: As a veteran activist over many decades, how would you summarize your life story to date?

Malcom Gregory Scott: Mine is a story of fighting to survive, the random good fortune of timing, and redemption through gratitude. In 1987, when I was first diagnosed with HIV, I was told I might not live even another year. In fact, another six years would pass before I would experience full-blown AIDS, and, by then, rumors of a new class of medications then being tested for safety and efficacy had already begun to circulate. Although I was already in the terminal stages of the disease, the hope that drugs that actually worked might soon be available renewed my determination to fight for life.

Before I grew frail, I had been active in ACT UP and Queer Nation; the abstract collectivized fight for survival was a surrogate of sorts for the individual concrete struggle that had been so hopeless then. I was also fighting in another sense, because I was using marijuana illegally to combat AIDS wasting. Without it, I surely would have died before I finally got the miraculous new drugs. These new drugs, protease inhibitors, in combination with other drugs already available, changed the existential calculus. The fight for survival was no longer an abstraction; survival was a real possibility. Patients in the trials were doing so well that the drug companies were expanding them to include as many patients as possible. Unfortunately, one had to have at least 400 T-cells to qualify for the trials, so I was already far too ill to qualify; I had not measured even a single T-cell in more than a year.

But then an activist group that had spun off of ACT UP, the Treatment Action Group, pressured the FDA and the drug companies to implement compassionate access lotteries so that a few people who were very ill would be able to get these new drugs. I applied for two such lotteries that summer, and six months later, my number was randomly drawn. Today, I live in gratitude for my fighter’s constitution, my good timing, medical marijuana, the new drugs that came in the nick of time, and all the people (like my brilliant doctor) who helped me through the dark times.

AM: Can you tell me a bit about your childhood? When did you know you were gay, and what was it like coming out and being sexually active in the 1970s and ’80s?

MGS: I was born in Arkansas but grew up mostly in Mississippi, and lived briefly in Georgia and northern Virginia. I was the third of my mother’s three boys by my father, who worked as a bookie in Little Rock. My mother wanted a better life for us and divorced my father when I was six, then moved us to Oxford, Mississippi, where she resumed her education, ultimately receiving a doctorate in English literature from the University of Mississippi. There she also met her second husband, and they were married when I was eleven years old. Two years later, they had a son together, and with my two stepsisters from my stepfather’s first marriage, we formed a real-life, slightly twisted Brady Bunch.

I remember understanding I was different in some of my earliest memories, although I was probably eight when I fully realized that this had something to do with what I then understood as sex and gender. The ’70s were a time of liberation, actually, and sex was not a dirty secret in our family. My mother encouraged us to ask questions when we were very young and encouraged responsible behavior as we grew old enough to be sexually active. When I was young, public men’s restrooms were extremely active, many with graphic graffiti and glory holes. My father’s apartments were always in one of the singles’ communities popular in that era, and a weekend there was always educational. Stacks of adult magazines—like Playboy, Hustler, Penthouse, and especially the “letters” spin-offs these magazines also published—were the only reading material my father kept, and in those days they were all filled with references to bisexuality, homosexuality, and unconventional sexual behaviors. The art on his walls consisted of beer signs, astrology posters, and erotica. His female visitors were often flirtatious, and the scene at the pool sometimes ribald. I didn’t forego the opportunities presented by the liberal times, and became sexually active at a very young age.

The emergence of the Moral Majority at the end of the decade heralded a more conservative time to come, and in the autumn of 1980, just as I was beginning my freshman year at the University of the South at Sewanee, a small private Episcopalian college in Tennessee, we saw the election of Ronald Reagan and the rise of a conservative, evangelistic, and homophobic movement. Then, in June 1981, as if a sign from heaven that all their homophobia was justified, The New York Times reported the first cases of what would later be known as AIDS. It seemed clear very early into the decade: the 1980s would definitely be very different from the ’70s.

AM: What were the deciding factors that led you to join the Navy a few years later (in 1985)?

MGS: After I was run off campus for being a fag (a high school classmate outed me to our fraternity pledge class), I was not economically able to return to college, and the job market was very limited for someone with no degree. A test that detected HIV had just become available, but there was no such thing as an anonymous test back then, never mind a free anonymous test, so I couldn’t have afforded it anyway. When the Navy announced it would begin testing recruits, and not accepting HIV positive enlistees, I saw it as an opportunity to find out if I was HIV-positive at no cost, and to land a job with long-term prospects if I wasn’t.

A regular sex partner from when I was seventeen years old died in 1982 or ’83 from “GRID,” as it was then known. No one had yet proven the disease to be sexually transmitted, but we intuited it to be, so when I heard he died I assumed I must have it. Thus I was surprised when the Navy accepted me as an enlistee even after they drew my blood to test for HIV, suggesting I had been wrong, and had somehow dodged the bullet.

AM: How safe was it for you to be gay in this environment?

MGS: Like all the branches of service, the Navy offers havens—certain specialties, certain commands—where homosexuality is more tolerated. I had scored so well on the military entrance exams that the recruiter pushed me hard to enlist in the nuclear Navy, a command not known for such tolerance. So I was not safe in any sense, to an extent I did not realize at the time, and I could not be openly gay in any way. This was many years before “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” of course. The policy then was very strict, and enforcement sometimes very harsh.

AM: What was it like for you emotionally when you tested positive for HIV?

MGS: I admit I was afraid. I was not ready to die, but I was also subjected to so much messaging that told me I did not deserve to live. I had to overcome the culture in which I had come of age, and that is never easy. But I was lucky because I was never alone in this endeavor. From the moment I resolved to take a stand in defense of my own queer life as well as queer lives more generally, I was among loyal comrades.

AM: You’ve described the next phase as “throwing myself into furious years of activism.” Was that part of your survival strategy?

MGS: I have no doubt that activism gave me a needed outlet for my indignation. Without it, as the science of cortisone, adrenalin, etc., now confirms, the anger would have elevated my inflammation levels, and I might have been much sicker, much sooner. The activism, like the marijuana, was good medicine. Aside from the physiology of anger, though, activism connects us with a vital support system of comrades and allies, and gives us ways to reach outside of ourselves to help others, which is always healing, redemptive work.

AM: How would you describe your time at ACT UP and other organizations that you worked with?

MGS: Urgent. United. Uncompromising. We understood that the threat against us was existential and immediate. Our emotions, voices and actions were pitched accordingly. In terms of my survival, moreover, I would describe those years as the most important and meaningful. Had our collective activism not been successful, the drugs that saved my life would probably not have existed, and my personal engagement with activism gave value to what I believed would be my last years.

AM: What was it like to survive a near-death experience and then emerge into a time when effective anti-retroviral therapies finally became available?

MGS: The drugs snatched me from the grave at the very eleventh hour. Had I won the compassionate lottery to receive Saquinavir even a few weeks later, I may not have lived. And once I recovered, so much uncertainty persisted about the sustainability of the therapies and the qualities of the revived immune systems, that several years would pass before those of us so rescued were able to reasonably internalize the idea that we now faced a future.

AM: What are your thoughts on today’s generation of activists? To what extent are you participating in their efforts?

MGS: Today’s activists are killing it [in a good way]. Never before have there been more ways to resist, and more causes that deserve our outspoken resistance. Younger activists have a savvy for radical militant politics that I admire, and I think they have come of age exposed to more diverse influences than we enjoyed. Like others, I do see potential pitfalls created by the Internet: the lure of an activism limited to social media and never realized in the material world. But the opportunities for organizing created by this technology are unlimited. I often wonder whether ACT UP might have been even more successful if we had had e-mail, never mind smartphones and social media. At the same time, I think it’s important not to abandon some of the analog approaches to these problems, because they offer unique benefits not provided by the Internet.

When I left Florida for California in 2004, I told the gay paper in Fort Lauderdale that I wanted to retire from activism somewhere where marijuana and sodomy were legal. For a few years, I did indeed change gears, focused on my physical, mental, and spiritual health, and started a new life as a medical marijuana farmer. That in itself was revolutionary in my opinion, especially farming as we were, applying permacultural, regenerative farming techniques and relying on a collectivist economic model. I’ve also been trying to write the story of my near-death with AIDS, so my writing remains very close to my activism. And, of course, in recent years, I’ve taken to the streets just as we have all had to do, first to support the Black Lives Matter movement and to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline, and most recently to resist the current president at every opportunity. But I’m content to let younger people do the heavy lifting of leadership. This generation of activists boasts media sophistication and other skillsets that render us old-timers somewhat operationally irrelevant.

AM: What is your life like today?

MGS: Today I live in Portland, Oregon, where I spend my time gardening, working on my house, and writing my memoirs. For the last two years, my 79-year-old mother has lived with me. AIDS continues to be a challenge, and only now are health care providers beginning to understand the extent to which long-term HIV complicates the aging process. Many of the health issues facing me are typical of a man in his seventies or eighties, though I am only 56. The cognitive and psychological complications of long-term HIV disease, sometimes referred to as AIDS Survivors Syndrome, also require extra care and attention as the years mount. I try to remain physically and mentally active, recognizing that this is the key to remaining fit enough that I may continue to enjoy a quality life. Most importantly, I try to live without fear, which is easier having once faced illness and death.

AM: What is the legacy you hope to be remembered for?

MGS: This is really the hardest question to answer. Needless to say, I hope the book I’m writing might contribute to my legacy as a writer and as an activist. I hope people will remember my role in reclaiming the word “queer,” helping in the late 1980s and early ’90s to show the American queer Left why they should care about gays in the military, and advancing the cause of safe, legal, and affordable access to medical cannabis.

AM: Is there anything you’d like to add?

MGS: I think we are again entering dangerous times, in the US and around the world, and young activists will again be required to courageously put their bodies on the cogs and levers of the machine in order to defend our shared humanity and to rescue the planet from the profligacy of capitalism and false religion. For me, anarchism is not about a state or condition, but about a movement away from domination in all its forms, a movement always toward autonomous self-actualization within the secure framework of mutually recognized interdependence. As the darkness seems to fold around us, I have faith that if we will take each other by the hand and trust the earth, the light will find us again. We will have to fight, and I remain ready to do my part.

A. Miller, a Midwestern poet and essayist, has appeared in Making Queer History, The New Verse News, and others publications.