The following text is drawn from the catalog for an art exhibit called Graphic Intervention: 25 Years of International AIDS Awareness Posters: 1985–2010, which ran at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston last fall. The international poster collection of James Lapides formed the basis for the exhibit; several of the 153 posters that were on display are shown here.

THIRTY YEARS AGO the AIDS virus began killing thousands and infecting hundreds of thousands more. Although the Western world was hit unaware, the disease had been coursing through the world’s bloodstream for many years. When Europe and the Americas were directly impacted, however, curative and preventative measures were gradually instituted.

With death tolls on the rise, mainstream and alternative media eventually rallied to dispel demonizing half-truths and myths. It wasn’t until 1993 that the film Philadelphia with Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington made a dent in the wall of denial (and fostered the fashion for red ribbons on Oscar night). As more victims in the creative industries were struck down, international celebrities took to their soapboxes. Amid their heartfelt clamor, and in addition to a surge of attention in the kinetic mass media, the most prodigious barrage of information was disseminated through a more static medium: the printed poster.

Even in this hyper-saturated media and information age, printed pieces of paper continue to influence and inspire, incite and inform. The poster, a universal medium and arguably the most affordable means of conveying important messages, has been essential in the war against AIDS. Before viral videos circulated throughout the Internet, posters held sway and crossed all boundaries. Even today, posters go where WiFi cannot.

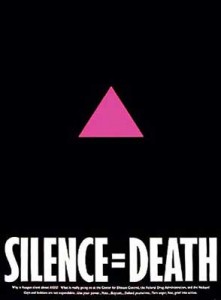

Posters were (and are) the great equalizer in countries where paper is a high-tech medium. Although verbal and visual languages and dialects may be different, a poster can make the difference between ignorance and understanding. A poster campaign, in fact, triggered my own wake-up call to the issue—and this was no thanks to public health officials at the time. In late 1988, Gran Fury, the graphic design spin-off arm of ACT UP, launched a massive attack throughout New York City to caution gays and enlighten straights. I wasn’t the only one who was ignorant of the facts. Accurate Health Department information was hard to come by, even though the gravity of this illness demanded accessible educational materials. For me, awareness began with an enigmatic pink triangle (with its reference to Nazi concentration camp branding of homosexuals) and the slogan “Silence = Death” (at first an enigmatic but later highly recognizable slogan).

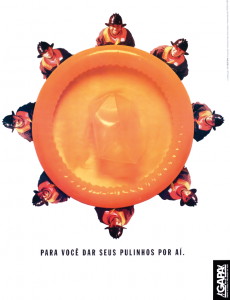

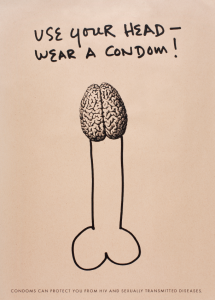

My education continued with posters that celebrated alternative lifestyles and love-styles while promoting condom use for all. The most startling and effective Gran Fury message was placed on the outside of city buses and read “Kissing Doesn’t Kill, Greed and Indifference Do.” In a style reminiscent of Benetton ads, couples of different races (man and woman, man and man, woman and woman) fondly kissed. The image itself was doubtless a shock to many, but the overall message, that AIDS existed but it needn’t be feared or cause prejudice, was even more profound. This and subsequent advertisements by ACT UP, Gay Men’s Health Alliance, and other groups eventually led to mass awareness of the epidemic.

Every country hit by the disease—which is almost every country—tapped into posters for their persuasive and propagandistic powers. It isn’t a new phenomenon. Cautionary posters were tools of education long before AIDS. In the 1940’s and 50’s, syphilis and gonorrhea were the scourge, but it wasn’t until posters promoting prophylactics were distributed that prevention and treatment measures were discussed in public. Decades later, it was more important that AIDS be better understood, as it was long treated as mysterious and sinister.

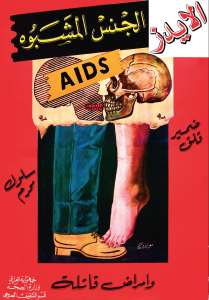

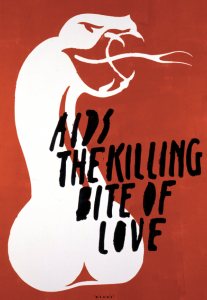

Initially, even New York Times obituaries didn’t report AIDS as a cause of death. But eventually the reality was as infectious as the virus. By the early 1990’s, almost every day one or more obituaries referenced AIDS as a cause of death. Not since the 1920’s, when infantile paralysis was such a life-threatening specter, had a health emergency evoked such fear—or such an aggressive visual response. Just as the iron lung became the visual icon of polio, the emaciated, cadaverous human form covered with lesions, as seen in a mid-1990’s advertisement produced by Oliviero Toscanni and Tibor Kalman for Benetton, came to symbolize the human suffering of AIDS. With mainstream media treating it as a bona fide illness, not some mere perversion, more varied forms of information dissemination were developed. Around the globe, different cultures visualized AIDS in ways that were acceptable to their populations.

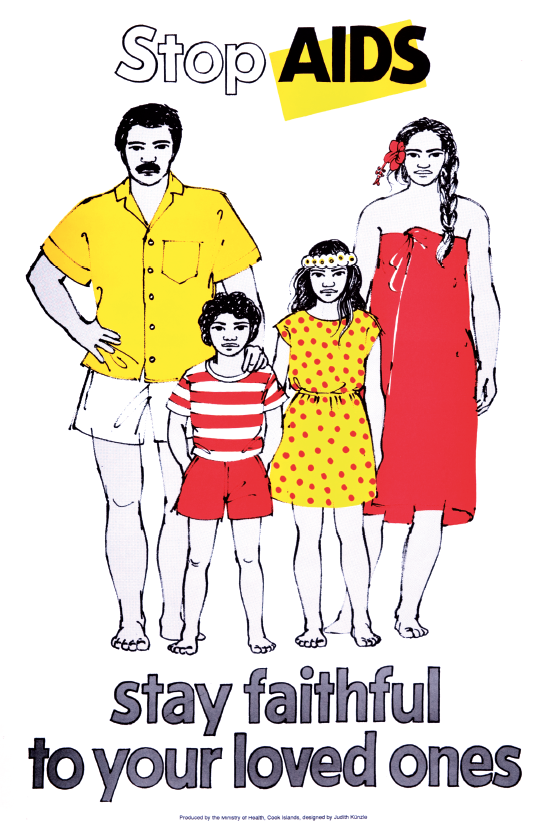

How many different ways are there to talk about hiv/aids? It’s one thing to show the Benetton ad in a magazine or on a billboard, yet another to show it on television. A static image can be viewed in a contemplative way; a kinetic one could be construed as an attack on an unwitting viewer. Understanding what the public will accept at any give time or venue (what the industrial designer Raymond Loewy called “most advanced yet acceptable”) is not an exact science but demands good instincts. Designing in particular vernaculars, across different borders, and for varied constituencies is what makes the posters so distinctive as we go from one country to another.

No single design language fits all problems. The level of intensity of a message must be weighed against the kind of response or action that is wanted and expected. With AIDS, it’s not enough to advertise to fund a cure or advocate prevention; degrees of emotional investment must be considered. Is that done through design, image, or text? Do the standards of “good” or “modern” design matter? Is a message best served by simplicity or complexity? And what are the cultural taboos—the lines that artists and designers cannot cross?

used to adorn young women’s bodies at social celebrations. Here the henna-designed

hands symbolize sex and marriage. The playful manner in which they hold the condom

conveys happiness and health.

In the West, many AIDS posters attacked the issue quite polemically. But in India, for example, they more touchingly conveyed stories designed as warnings to alter common behavior. Using vernacular imagery rendered in popular styles, one such poster written in Hindi states: “My beloved has gone overseas to earn a living. I hope he does not return with AIDS. Protect yourself from a strange woman, so that AIDS may never enter. AIDS spreads through unprotected sex!” Another from India shows an even more compassionate side: “People suffering from AIDS need love. Not disgust, not abandonment, but just love.” In Uganda, heavily hit by AIDS in the early 1990’s, posters were designed to encourage detection and treatment, like this: “What does a person with AIDS look like? AIDS can look like many other diseases. Don’t be confused. Don’t spread rumours. See a qualified medical person for tests if you think you or someone you know may have AIDS.” Or this: “Can you spot which person carries HIV? The answer is no! The AIDS-Virus can hide in a person’s blood for many years. People who carry HIV may look and feel healthy, but they can still pass HIV to others!”

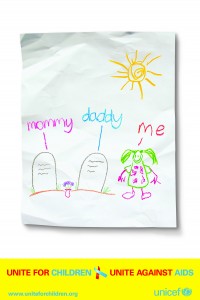

The most politically and emotionally charged posters are not necessarily the best designed or conceived in the world’s pantheon of posters. But they hit the message like a hammer. “I Have AIDS / Please Hug Me: I Can’t Make You Sick” is a heart-wrenching plea, and the poster’s faux childlike drawing and lettering serve to underscore the message. Also compelling are the tulip and the rose in the familiar “Make Love, Not AIDS” poster, which unfortunately evokes the æsthetic of a tired greeting card; but if it works, who can complain? More intelligently conceived, the unicef “United for Children, United Against AIDS” poster, showing a paper boat floating in a red sea of mines, may be too clever for its audience, or just clever enough. The same might be said for a poster showing a shark fin emerging from a sea of blue with just the word “AIDS.” Nice design, but other than cautioning the viewer to beware, what is the message? One of the more powerful pieces is “Condom-man,” which speaks in the universal language of the comic book in a witty way that informs rather than preaches.

Attempting to evaluate these posters is not easy—and probably not necessary, since each nation has its own unique priorities. Effectiveness is not decided on whether the typography is pristine or the drawing is nuanced. Although the niceties help (and for designers are essential), the viewer’s ability to comprehend is the deciding factor. If “AIDS: Don’t Be Afraid / Be Aware” captures your attention, then the poster has done its job. If “Senza? Senza di me” lulls you into the security that this is a billboard for an everyday product, like milk, and then lobs the “Stop AIDS” bomb, then bravo!

Attempting to evaluate these posters is not easy—and probably not necessary, since each nation has its own unique priorities. Effectiveness is not decided on whether the typography is pristine or the drawing is nuanced. Although the niceties help (and for designers are essential), the viewer’s ability to comprehend is the deciding factor. If “AIDS: Don’t Be Afraid / Be Aware” captures your attention, then the poster has done its job. If “Senza? Senza di me” lulls you into the security that this is a billboard for an everyday product, like milk, and then lobs the “Stop AIDS” bomb, then bravo!

Twenty-five years have passed since the first AIDS posters were created. They reveal the use of graphics as an information tool and intervention weapon, and show that a balance must be struck between æsthetics and communication. Can posters stop a disease? Obviously not. But depending on where they are displayed and who sees them, they can make a huge difference. They may only be made of paper, but their message can be tough and durable.

Editor’s Note: Great thanks go to Javier Cortés, co-curator of the exhibit, for his help and consultation in the preparation of this article.

Steven Heller, author of numerous books on graphic design and popular culture, is co-chair of the Designer as Author Program at the School of Visual Arts, New York.