“WE CAN’T MARRY even if we want to. But if we moved in, could we take the heat?” So sings the Australian rocker Alex Lahey on the song “There’s No Money.” Take a listen to the acoustic version available on Spotify’s “Badass Women” playlist. Lahey is a badass, and I should know because I interviewed her before her gig at the Lost Lake Lounge in Denver. At the tail-end of her I Love You Like a Brother album tour, she joked that life on the road was full of too many hamburgers and not enough sleep.

After touring the U.S. by van for two months—with a stop at Late Night with Seth Meyers to make her TV debut—the 25-year-old Lahey was ready to return home to Melbourne for the holidays. Backstage—where a bottle of whiskey was conspicuously positioned for later—I asked her about growing up gay Down Under, to which she replied: “It’s not about places. It’s about families and people looking out for each other. I’ve been really fortunate with an ideal upbringing. A big adjustment for me was realizing that may not always be the case—the realization that your partner’s family is not going to accept you.”

Here is a musician who writes pop ballads as catchy as they are forceful. Her music turns on the tension between being young, and thus feeling trapped in unfulfilling romantic relationships (par for the course), and hoping for a better world out there, waiting to be found. A song like “Lotto in Reverse” is about female erotic reveries and taking note of a Barbarella poster in a girlfriend’s bedroom, while “You Don’t Think You Like People Like Me” is an anthem about being misunderstood. In it, she essentially sells herself to a lover: “Maybe I’m the one exception that could last forever.” Similarly, there is a secret romantic hidden in a line from the drinking song “Every Day’s the Weekend”: “We should ride this wave to shore.”

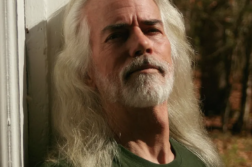

Giulia McGauran photo.

Alex Lahey (born “Alexandria”) has eclectic tastes. She grew up listening to the Ramones, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and even Dolly Parton. Surely this is part of her appeal, which transcends social groups. At the concert, there were scores of drunken straight guys bobbing their heads and mouthing the words to each and every song. During her set, she covered the one-hit-wonder Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn” (1997) as an homage to her fellow Australian. Trying to get at how Lahey’s political sense informs her art, I dissected a lyric of hers like it was a frog. “Does the song ‘I Love You Like a Brother’ have a queer subtext?” The effort backfired spectacularly. “It’s a song that is literally about my brother,” she deadpanned. “I was playing with the phrase without playing with it.” I pointed toward the Rufus Wainwright T-shirt I was wearing, however, and said that certain pioneers paid the price so that the next generation of artists could treat sexual orientation as if it’s no big deal. “People are just people,” she said, and explained that sexuality shouldn’t be a person’s defining feature.

Colin Carman, PhD, teaches lgbtq film studies at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction, Colorado.