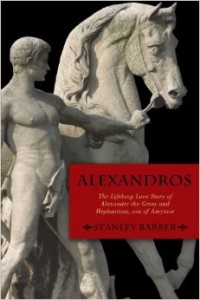

Alexandros: The Lifelong Love Story of Alexander

Alexandros: The Lifelong Love Story of Alexander

the Great and Hephæstion, Son of Amyntor

by Stanley Barber

iUniverse. 334 pages, $19.95 (paper)

STANLEY BARBER STARTS OFF by declaring that this work is “written as a libretto for a sung-through musical,” repeating this in the Epilogue. I confess that I can’t see it working as such. It is written in various lengths of short verse, but the style is reminiscent of nothing so much as those 1950’s Italian toga movies, or the very serious films (in English) of the great Greek tragedies that we were shown in high school back then.

Thus, for example, Antipater tells King Philipos, Alexander’s father: “May I suggest/ You invite all the elders/ Of all the city-states of Greece/ United as one nation,/ Your daughter’s marriage to celebrate.” When Philipos’ male lover Pausinais is killed, the king vows: “And I will find a way/ For this outrage and defilement to repay.” Olympias, Alexander’s mother, chides her son’s male lover, Hephæstion, telling him: “But you two have passed that time [of experimenting],/ And still the bond is strong,” and tells her son “Between you and the throne/ There must be no impediment./ A male living heir there must not be.” When the style does on occasion become modern-sounding, it seems like a jarring mistake, as when Kleopatra tells Alexandros “You better, or I will have you thrashed.” I can’t imagine such diction being set to the sort of music that is used in musicals today.

At times it seems that this might work as an opera libretto—much less lucrative, I realize, but perhaps more realistic. It would need to be drastically reduced in length, but there are occasional love duets for Alexandros and Hephæstion that could make for powerful opera, even if they do sometimes conclude with homosexual lovemaking, which would be largely new on the operatic stage but certainly not unappreciated by a significant segment of the American opera-going public, myself included. There are also scenes of Alexandros stirring up his troops that one could imagine as powerful choral numbers.

There are even scenes that remind me strongly of some of the great repertory operas, such as in Act I, Scene 11, where Olympias tells Hephæstion that he must leave her son until after Alexander has become King of Macedon. It reads very much like Germont telling Violetta Valéry in La Traviata that she must leave his son Alfredo so that Alfredo’s sister can find a respectable middle-class husband. When an older Hephæstion tells Alexander’s young male lover Bagoas that he is not jealous of their relationship, I was waiting to hear the Marshallin in Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier sing “Na ja” as she watches her erstwhile lover Octavian kiss his soon-to-be young bride Sophie.

In the end, however, at least at its current length, this opus is most likely to remain a book to be read rather than any kind of theatrical work. It is 300 pages of sometimes rhyming verse that recounts the major events in the life of Alexander the Great in strictly chronological order, from his youth in Macedon, where his mother schemed to put him on the throne after his father took a second wife and sired more children, to his death in the Near East. Some of the intimate scenes with Hephæstion worked for me. Some of the public scenes, such as those between Alexandros and the Maharaja Poros, reminded me of the “I can be nobler than you” scenes in Pierre Corneille’s untranslatable 17th-century verse tragedies. Some scenes make no effect, even if they are historically accurate. Even as a text to be read, Alexandros might fare better as a shorter work.

________________________________________________________

Richard M. Berrong is the author of In Love with a Handsome Sailor, a gay reading of the novels of French author Pierre Loti.