QUEER ARRANGEMENTS

QUEER ARRANGEMENTS

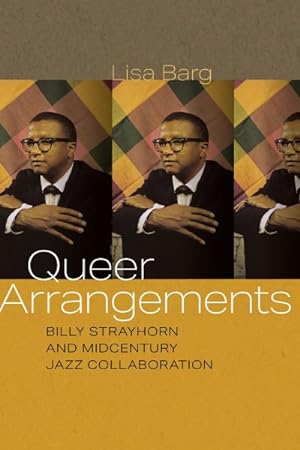

Billy Strayhorn and Midcentury Jazz Collaboration

by Lisa Barg

Wesleyan Univ. Press. 288 pages, $24.95

BILLY STRAYHORN (1915–1967) was a mid-20th-century jazz pianist, arranger, and composer who toiled for three decades under the long shadow of Duke Ellington. The two men met in 1939, and Ellington immediately hired Strayhorn as second piano and arranger for the Duke Ellington Orchestra. In that capacity, Strayhorn also composed many of the jazz standards associated primarily with Ellington: “Take the ‘A’ Train,” “Johnny Come Lately,” “Chelsea Bridge,” “Something to Live For,” “Lush Life,” and more. He composed major sections of the song suites attributed to Ellington, such as “Black, Brown and Beige” and their resetting of “The Nutcracker Suite.” He also made groundbreaking vocal arrangements for Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, Rosemary Clooney, Billy Eckstine, and other jazz singers of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and early ‘60s.

Since Strayhorn’s death, a handful of writers have worked to rescue him from Duke Ellington’s shadow. David Hajdu’s 1997 biography Lush Life and Walter van de Leur’s Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn have solidified Strayhorn’s position as a major force in American jazz. To those titles we can add Lisa Barg’s new Queer Arrangements: Billy Strayhorn and Midcentury Jazz Collaboration, a scholarly examination of Strayhorn’s work and life as a queer Black artist working in a time of overt racism and homophobia.

Barg approaches Strayhorn and his working relationships through the three lenses of queer theory, critical race theory, and musicology. There are lengthy sections of the book that are rife with insider lingo and academic jargon from those three subdisciplines. Some passages are nearly indecipherable without a dictionary of queer Black music theory. The book reads like a graduate school thesis or a forced “publish or perish” project (with 48 pages of footnotes) and clearly was not written for the casual reader.

If, however, you’re able to wade through the jargon, this book contains some interesting revelations about Strayhorn’s life and work. For example, regarding his decision to work somewhat anonymously as Ellington’s arranger and sometime co-composer, Barg quotes “an anonymous fellow Black gay jazz musician” as saying: “Strayhorn … had the strength to make an extraordinary decision … not to hide the fact that he was homosexual. And he did this in the 1940s, when nobody but nobody did that. Billy could have pursued a career on his own … but he’d have had to be less than honest about his sexual orientation. Or he could work behind the scenes for Duke and be open about being gay. It really was truth or consequences, and Billy went with truth.” This consideration also informed Strayhorn’s decision to live for extended periods in Paris, the center of European jazz, where he experienced only a fraction of the racism and homophobia he encountered in the U.S.

If, however, you’re able to wade through the jargon, this book contains some interesting revelations about Strayhorn’s life and work. For example, regarding his decision to work somewhat anonymously as Ellington’s arranger and sometime co-composer, Barg quotes “an anonymous fellow Black gay jazz musician” as saying: “Strayhorn … had the strength to make an extraordinary decision … not to hide the fact that he was homosexual. And he did this in the 1940s, when nobody but nobody did that. Billy could have pursued a career on his own … but he’d have had to be less than honest about his sexual orientation. Or he could work behind the scenes for Duke and be open about being gay. It really was truth or consequences, and Billy went with truth.” This consideration also informed Strayhorn’s decision to live for extended periods in Paris, the center of European jazz, where he experienced only a fraction of the racism and homophobia he encountered in the U.S.

Also of note is Barg’s examination of Strayhorn’s relationships with Lena Horne, Herb Jeffries, Rosemary Clooney, and Ella Fitzgerald, all of whom benefited from Strayhorn’s friendship as much as from his skill as an arranger and pianist. Lena Horne, in a 1980 interview, commented: “We were both at that time necessary to other people, me as a provider, Billy as Duke’s collaborator. But when we were together we were free of all that.” Strayhorn’s relationship with Horne was that he wrote, arranged, and polished songs for her nightclub act. (“Billy rehearsed me. He stretched me vocally … he wrote arrangements that had my feeling in the music.”) It was, Barg remarks, an example of “queer collaborative dynamics at the intersection of the personal, social, and the musical.”

Similarly, when it came time to write arrangements for the album <em>Blue Rose: Rosemary Clooney and Duke Ellington and His Orchestra</em>, Strayhorn and Clooney became “soulmates.” Clooney was pregnant and spent a great deal of time in bed as Strayhorn took care of her and nursed her back to health. When they did work together, Clooney remarked: “[I]t was like I was working with my best friend. I wanted to do my best for him … [he]was so completely unthreatening and uncontrolling and so completely in charge.”

One of the longest sections of the book concerns the creation of Strayhorn’s solo project <em>The Peaceful Side</em>, recorded in late-night sessions in an underground studio in Paris with local musicians. Unfortunately, parts of this section are among the most difficult to read. Barg’s intricate reading of Strayhorn’s scores for some of the songs is as complicated as a critic’s <em>explication de texte<em> of James Joyce. The section does, however, attest to the freedom and joy that Strayhorn experienced while working with French jazz musicians, most of them queer and Black as well.

Hank Trout is the former editor of A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.