LAST OCTOBER, as I watched the Discovery Channel special “Discovering Ardi,” I could picture the religious right going into meltdown over this latest possibility of a “missing link” in human evolution. The discovery of Ardi, and analysis of that discovery by 47 scientists, had just been published in Science magazine. Ardi knocks one more brick out of that ragged wall of biblical arguments built by creationists—that God got inspired around 6,000 years ago and made the world in six days. The U.S. media went wild, with the Irish Times proclaiming Ardi to be “a mother of all of humanity.”

Ardi may also knock a brick or two out of another wall—that of conventional evolutionist dogma. Some scientists can be no less dogmatic than scripturalists when they set their feet in concrete on a

position that they believe to be settled. Already there are hot debates about which prehistoric primates Ardi was related to, and what sex might have been like in Ardi’s world. We GLBT people can add our own questions about sexual orientation and gender differences that may have left their fossilized footprints upon that distant horizon.

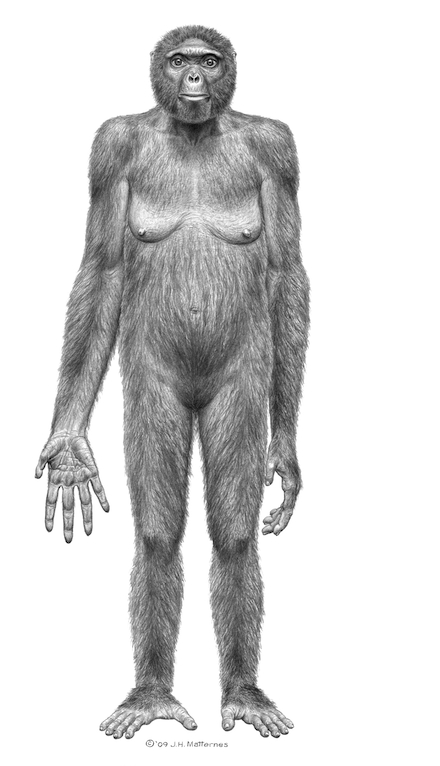

Ardipithecus ramidus, a.k.a. Ardi, lived around 4.4 million years ago in what is now a desert in Ethiopia. She stood about four feet tall, weighed perhaps 110 pounds. According to her discoverers, Ardi’s frame combined both ape-like and humanoid characteristics. Her skull had a primate look and a small brain, with teeth that included a pair of small canines. Although her feet had a thumb-like big toe that enabled her to grasp tree-limbs, her pelvis and femurs were shaped for walking upright. Her fingers and flexible wrists were also much like ours, making it impossible for her to “knuckle walk” on all fours in the manner of chimpanzees and other great apes.

It was in 1994 that paleo-anthropologist Tim White and his field team were working in those desert hills and an Ethiopian member of the team spotted the first shattered bits of what turned out to be a nearly complete fossilized skeleton. It was located in an area where fragments of dozens of other Ramidus individuals are also eroding out of the dry, crumbly, many-layered hills. But there are only a few reasonably intact skeletons of early hominids from the long period after our line split off from that other hominids some six million years ago, so this was regarded as a rare find. White’s international team painstakingly reconstructed the skeleton over a fifteen-year period. It was eventually identified it as female and given the nickname Ardi, an Ethiopian word for “ground” in recognition of her apparent life as a ground-dweller.

If they’re right, Ardi lived around 1.2 million years earlier than “Lucy,” an Australopithecus that was heretofore classified as our earliest upright-walking relative. Ardi may or may not be a direct human ancestor. Scientists are still looking for an earlier creature that may have lived closer to the fork at which the proto-human line parted company from other hominids in the evolutionary timeline. But, according to White’s team, Ardi could well be more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees. Thus hominids who walked upright appear to have had their own branch of evolution that began much earlier than scientists had thought.

According to White’s team, Ardi’s discovery—along with a few others that have recently come to light—radically rewrites the accepted account of human emergence. Prior theories placed our ancient ancestors on grassy savannahs in east Africa. There they supposedly had no trees to climb, so they started walking upright in order to see over the tall grasses for safety and for hunting success. But Ardipithecus fossils are found in a region that’s also rich in fossils of ancient trees and forest-dwelling animals, including predators like big cats. In fact, Ardi’s flat feet, with their splayed-out big toes, might have made it hard for her to run very far or fast. She wouldn’t have lasted long on the savannahs without a handy tree to scramble up in case of a predator attack. To be sure, there are some evolutionists who disagree with White’s reading of Ardi’s bones. These scientific arguments will doubtless last until that older fossil is found.

But, of course, it was the creationists who rushed most urgently to the barricades. Claude Mariottini, an Old Testament professor at Northern Baptist Seminary, trumpeted on-line: “The controversy between science and Scriptures is an issue that will not go away anytime soon. … Christians believe human beings were created in the image and likeness of God, human beings are different than the animals. And honestly, when I look at the recreation of ‘Ardi,’ I do not see any family resemblance.”

Anticipating the creationists’ consternation over Ardi’s human-like features, University of Minnesota biologist P. Z. Myers jibed: “Brace yourself, gang. The creationists are going to be claiming that this shows humans were created first, and all of these other hairy beasts the paleontologists are digging up are just degenerate spawn of the Fall.”

The Institute of Creation Research took a predictably puritanical tack, accusing Ardi’s discoverers of stooping to crass marketing with their reconstructed portrait of her, by portraying her with breasts, they fumed, which “look essentially like those of human females, albeit hairy. Research shows that men notice nude images. Advertising strategies have made extensive use of the observation that ‘erotic, suggestive and nude female models have a particularly strong attention-getting impact among male consumers.’ What better way to attract attention than to portray Ardi with overt human female characteristics?”

Sexual Relations among the Ardipithecus

As if to torment the creationists ever more, White’s team has waded boldly into theorizing about Ardi’s sex life. Their theories start with her teeth. Most early primates had (and their direct descendants still have) two large canine teeth that males use in their dominance contests and in aggressive sexual behavior toward females. But Ardi’s canines are relatively small, so her discoverers speculate that pair-bonding may have been developing, with females exerting more control in the mating process than with other primates. Females of her species may have been selecting for males with smaller canines, leading to a gradual decrease in their size.

One question that White didn’t tackle is a big one: when did evolution bring the emergence of our human-style breeding cycle? Wild primates, and many non-primates as well, have breeding cycles that are seasonally regulated to ensure that offspring are born when food is abundant in the environment. Some mammals are timed to have just one birth during a solar year. But humans today can conceive and give birth in any month of the year, including the dead of winter, even in northern climates. This variation may have developed as a result of our emerging ability to use tools to adapt to otherwise inhospitable habitats—to create a protected environment, complete with warmth and stored food, that could allow babies to survive at any time of the year.

Ardi’s discovery also pushes back the possible horizon for questions about the origins of homosexuality, bisexuality, and gender variants. For some years now, scientists have been accumulating evidence for homosexuality in animals from penguins to horses. Most important for this discussion is the growing body of evidence for homosexual behavior among other primate species, especially our closest relatives. According to Canadian anthropologist Paul L. Vasey in International Review of Primatology, “Available data indicate that this behavior [same-sex sexuality] is phylogenetically widespread among the anthropoid primates, but totally absent among prosimians. … It appears to be a more common pattern under free-ranging conditions.”

In 2004, even the National Geographic earnestly went looking for data on this fascinating subject—and found female macaques happily engaged in what we would call lesbian lovemaking. Also, according to National Geographic, “The bonobo, an African ape closely related to humans, has an even bigger sexual appetite. Studies suggest 75 percent of bonobo sex is non-reproductive and that nearly all bonobos are bisexual.” Thus the prevalence of homosexuality and bisexuality in our closest relatives is a matter of record.

Here’s where Ardi’s reduced canine size hits home. The bonobo is one of the only two extant species of the chimpanzee genus, the other being the larger and more widespread common chimpanzee. Despite their physical similarity, the two species display marked differences in social behavior and organization. As egalitarian and peace-loving as the bonobo tend to be, the common chimpanzee displays patterns of male aggression and dominance in relation both to each other and to females. As it happens, the latter species has considerably larger canine teeth than does the bonobo—one of the prominent physical differences separating the two. What we know about the bonobo, in addition to its gentleness and gender equality, is that members of a troop tend to engage in easy-going physical contact with one another, including sexual contact, and that this behavior includes both opposite-sex and same-sex activity. Ardi’s relatively small canines suggest that a similar pattern might have been emerging for this intermediate species, one in which males did not dominate females or compete aggressively for resources, but instead a situation closer to that of the bonobo, characterized by free-floating sexual liaisons and frequent eruptions of nonprocreative sex.

What the bonobo example shows is that homosexual and bisexual behavior can form a positive part of the troop’s overall social life. In her 1982 book Primate Paradigms: Sex Roles and Social Bonds, Linda Marie Fedigan writes about the lesbian-type relationships that she saw among Japanese macaques, which she called “consort bonding.” Writes Fedigan:

We found homosexual behavior, which took place in the context of definite consort bonding, to be part of a larger pattern of female sexual initiative. While homosexual behavior is not directly functional in the sense of procreation, it may be part of a larger sexual pattern which is adaptive in terms of reproduction, or it may have other significance for social living. For example, in our study we found that females who had engaged in homosexual consorts during the mating season were likely to remain affinitively bonded (friends) throughout the year in contrast to male-female consort pairs which were not translated into year-round bonds. Since sexual partners are almost always unrelated, these friendships cross-cut matrilineal lines and are a potential source of alliance and bonding.

Female-female relationships like these, among female primates, might be valuable as support networks for defending the young or dealing safely with outbreaks of aggression within the troop.

Non-Breeders in Non-Human Communities

Some gender variations that exist in humans may have their origin in early hominid evolution. In much of the animal world, the nature of genetic sex and sex chromosomes is far more complicated than it is in humans. Most primates have the same XX/XY system that we have. But biologists have learned that a certain percentage of animals, like some humans, are born with intersex variants of what would be the normal sex-chromosome configuration for that species. An example would be humans who are configured as XXY or XYY. (This question has been seriously discussed by scientists such as Frances D. Burton in “Ethology and the development of sex and gender identity in non-human primates,” published in the Dutch journal Acta Biotheoretica, March 1979).

In other animal societies—especially among the so-called “higher animals”—intersex individuals are not bullied or hounded out of the community. Instead, they share fully in the life of the group and contribute to its collective survival, even though they typically do not contribute to its gene pool. For example, as a member of a large grazing herd, such individuals form part of the protection-in-numbers factor. In a wolf pack or meerkat colony, an infertile female or male can still play a vital role by hunting for food and helping to care for the alpha pair’s pups. In a band of pre-human hominids such as Ardi, perhaps a non-reproducing female could have served as a free-floating aunt to help her sisters raise their young, for example.

Only among Homo sapiens, and only in recent millennia, have we seen the emergence of a fierce objection to full participation of non-conforming individuals in the social life of the community. Only among humans is there a focused attempt to isolate or oppress non-reproductive individuals. It’s chilling to note that strict Christian creationism is the product of a religion that aims to obliterate all non-heterosexual and non-gender-conforming members of society.

If the six-day creationists are ever forced to admit that evolution really did happen over many millions of years, they’ll also have to admit that they themselves—along with the rest of us—evolved out of those ancient landscapes where a whole range of sexual behaviors was not only natural but also part of a global dynamic in which all creatures moved ever onward, inch by inch, into their future. Indeed, they might be confronted with the fact that they must carry genetic traces of that GLBT contribution in their own DNA. They might owe their personal existence to those richly textured support networks that all the different sexual orientations contributed to that shared moment on the great time-line when Ardi’s ancestor took her first steps on two feet.

Patricia Nell Warren is a novelist and essayist whose latest book of nonfiction is The Lavender Locker Room: 3000 Years of Great Athletes Whose Sexual Orientation Was Different (2006). This article is based on a post at the Bilerico Project website on 10/14/09.