Donald Moffett: The Extravagant Vein

Donald Moffett: The Extravagant Vein

by Valerie Cassel Oliver

Skira/Rizzoli. 224 pages, $65.

A TWENTY-YEAR retrospective of Donald Moffett’s work titled The Extravagant Vein has been mounted by the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, where it will remain on view until January 8, 2012. After that, the exhibit will travel to the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery of Skidmore College in Sara-toga Springs, New York, and then (next June) to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Accompanying the exhibit is a handsome, full-color catalog, published by the Houston museum and Skira/Rizzoli, which includes essays by Bill Arning and Russell Ferguson, an interview with Douglas Crimp, and an overview by exhibit curator Valerie Cassel Oliver.

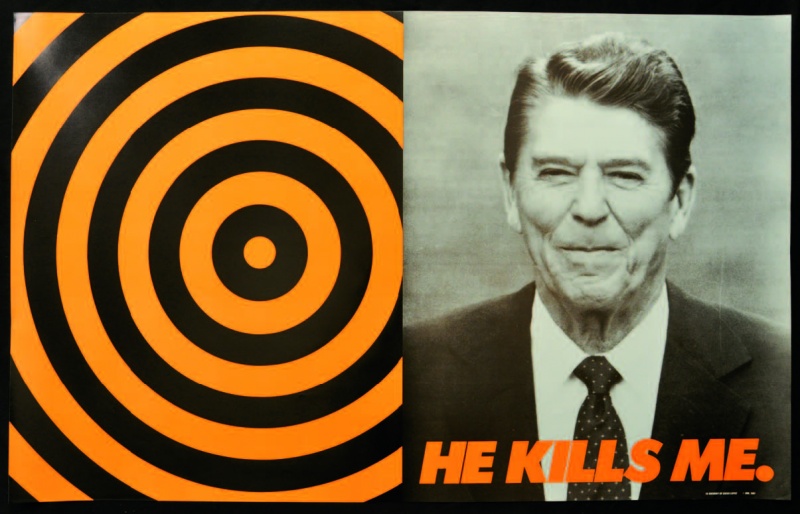

Moffett is perhaps best known for his work as an AIDS activist while a member of the artists’ collective Gran Fury in New York in the 1980’s. Gran Fury was the propaganda arm of ACT UP, and its artists’ visual images included such iconic posters as  “He Kills Me” (1987), the “Silence = Death” logo (1987), and the “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” series. From 1989 to 2001, Moffett worked with the graphic design studio Bureau, which he cofounded with fellow Gran Fury member Marlene McCarty, with whom he worked on activist and commercial projects.

“He Kills Me” (1987), the “Silence = Death” logo (1987), and the “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” series. From 1989 to 2001, Moffett worked with the graphic design studio Bureau, which he cofounded with fellow Gran Fury member Marlene McCarty, with whom he worked on activist and commercial projects.

Moffett’s art will probably have scant appeal to those whose tastes run to sexy and erotic representation, as his interests probe more cerebrally into the socio-political issues of being gay. And given the context of his early involvement with the AIDS crisis—he came to New York from Texas at age 23 in 1978—it’s understandable that Moffett’s art is tied inextricably to the larger issues of gay liberation. A lithographed poster from 1987, “He Kills Me,” juxtaposes an orange and black target with an unflattering photo of Ronald Reagan, emphasizing the president’s naked indifference to the growing epidemic. These artistic explorations are clear examples of the personal as the political.

For the early 90’s, the exhibit and catalog offer bodies of works that are non-AIDS related, such as “Gays In the Military” (1990), a series of reproductions of celebrated 19th-century Civil War officers with discreetly applied captions stating their alleged—and humorously outrageous—gay sexual proclivities. This series, along with another one that also deals with historical figures, “Nom de Guerre” (1991), was created during cultural debates and discussions about gays serving in the military and the resulting “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

There were additional personal art projects, including his 1993 homage to murdered Navy radioman Allen R. Schindler, who was brutally killed by a shipmate for his sexual orientation. For a related series of 18 drawings, “Mr. Gay in the USA,” Moffett attended the sentencing of another killer, Ronald Edward Gay, accused of the murder of Danny Lee Overstreet and the maiming of six others in a Virginia gay bar. Commenting on these simple line drawings of visual elements in the courtroom, New York Times critic Holland Cotter characterized Moffett’s series as part of “this artist’s continuing study of the shifting positions of normality and strangeness, in which he lets the facts speak for themselves.”

By the mid-90’s, Moffett was beginning to feel burned out, drained by the ongoing struggles and losses of the AIDS crisis, including the death of his lover, and the demands of the Bureau studio. Henceforth, Moffett’s work took greater strides to address artistic issues, though his focus on gay sexuality remained central, if less obvious. He created oil on linen paintings that explored the use of paint in unusual ways, extruding paint with cake decorating tools in an effort to make it stand up rather than lie flat. These paintings were highly textured, monochromatic abstracts which resulted in a small 1996 exhibition titled “A Report on Painting,” marking a radical turn in his artistic journey to combine formal concerns with subtle social and cultural commentary. Another later series of larger canvases employed oil on linen with video projections of the Rambles in Central Park, long used as a gay cruising ground for anonymous trysts.

Beginning in 2007 through 2010, three series called “Gutted,” “Fleisch,” and “Comfort Hole” are subtle commentaries on openings and exposures, flesh, and bodily orifices. All are quite abstract, often monochromatic, and coolly nonsexual. The catalog’s essays are quite helpful in explaining the artist’s processes and intentions, keeping a clear focus on their cultural contexts.

While there are working gay artists who are not necessarily inspired by the more physical and visual aspects of their sexual orientation, it is refreshing to be challenged by one who takes the intuition of his sexuality to a more intellectual level. Moffett’s work is not for everyone, but it does illustrate the breadth of creativity of our visual artists, and this retrospective catalog pays appropriate homage to this highly regarded contemporary artist.

David B. Boyce is a freelance writer and an art curator in New Bedford, Mass.