DAVID WOJNAROWICZ

Hall Art Foundation, Reading, VT

May 10 to November 30, 2025

Artist-activist David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) came of age in New York’s 1980s East Village gallery scene, alongside Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. His art was highly political, angry, and belligerent, taking an aggressive stance that reflected the harshness of his adolescence on the streets of Manhattan, which included drug use and sex work. He also lived with AIDS. He was often in the crosshairs of the Culture Wars before his untimely death in 1992.

This exhibition’s centerpiece is an eight-foot-square, four-panel painting titled Dad’s Ship (acrylic and enamel on Masonite, 1984). It depicts an ocean liner in flames: billowy clouds and churning seas, layered with frantic brush strokes that allude to the psychological and physical abuse inflicted by the artist’s merchant seaman father. In the upper quadrant, an image of a prone dog floats in relief. On an adjoining wall hangs a painting of a mugging (collaged paper, acrylic on Masonite, 1982), its violence cartoon-like, a wristwatch, ring, and wallet flying into the air. A fiberglass model of a shark collaged with map fragments (1984) serves as a peaceful counterbalance to the mayhem in the paintings. Wojnarowicz often drew on animal imagery as a reassuring talisman.

The second gallery contains eleven sculptures of disembodied heads (acrylic on plaster, 1984). Each is embellished with its own distinct mix of torn-up maps, money, paint, and differently colored eyes. The artist’s idea was to represent what he called “the evolution of consciousness.” Bruises, gags, and deteriorated bloodied bandages also distinguish each head. Two painted globes and a repurposed supermarket poster stenciled with bestial imagery fill out the display.

The seventeen paintings and sculptures on view are political, but they contain little of the homoeroticism that was an essential part of Wojnarowicz’ dissident vision. Some inclusion of his media works, published screeds, and performance footage would have added considerably to the gestalt.

John R. Killacky

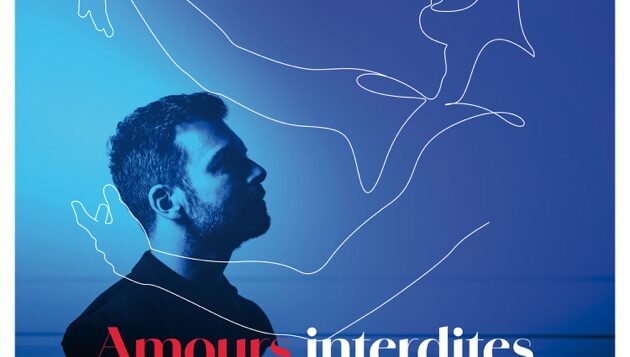

AMOURS INTERDITES

Played by pianist David Kadouch

Mirare Productions

It’s high time we had a CD devoted entirely to piano music by gay and lesbian composers—and not played by just any pianist, but by the internationally renowned David Kadouch. Born in Nice in 1985, Kadouch has been praised for his elegance, insight, emotional power, and eloquence as a performer—all of which are on display here.

“Hommage à Édith Piaf,” by Francis Poulenc (1899–1963), is a lovely, expressive opener, and his “Mélancolie” is also very affecting. Brilliant virtuosity is on display in Percy Grainger’s “Paraphrase on the ‘Waltz of the Flowers’” from The Nutcracker by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) and the “Variations on a Polish Folk Theme” by Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937), a colorful major work that ends with tumultuous exultation. Late-Romanticism also shines through in miniatures by the flamboyant Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) and the melancholic Reynaldo Hahn (1874–1947).

Perhaps the most surprising pieces are those by the great Polish harpsichordist Wanda Landowska (1879–1959), who reveals a dark and passionate soul in three works, especially the dramatic “Nuit d’automne.” An arrangement of the ever-popular “April in Paris” by Charles Trenet (1913–2001) makes for a perfect conclusion. In this imaginatively planned and executed program, Kadouch takes us into the intimacy of personalities who were sometimes bruised and sometimes liberated by their “forbidden loves.” I look forward to listening again many times to this exceptional disc.

Charles Timbrell

BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN

Directed by Ang Lee

River Road Entertainment

Rewatching a beloved film decades later can be crushing: Scenes that felt fresh and vital may seem mawkish; once-resonant themes can become embarrassing. Brokeback Mountain (2005), rereleased in theaters upon its twentieth anniversary, has lost none of its power. If anything, its relevance feels renewed as conservative culture warriors expand their attacks on the LGBT community and films centering queer characters seem in danger of disappearing. Seeing Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist again, tiny beneath the expansive Wyoming sky, with an entire society seemingly arrayed against their desire to be together, feels like an apt metaphor for the cyclical nature of history.

Heath Ledger’s performance as Ennis remains a startling portrayal of a borderline nihilist trying to survive an inhospitable world. He doesn’t dare dream of voicing his love for Jack—he can only express his feelings through violence or quiet, lonesome tears. As Jack, Jake Gyllenhaal intuitively understands and tries to accept Ennis as he is, saving their bloodied shirts like a valentine after a fistfight that is subtextually about Ennis’ inability to say he doesn’t want to lose Jack.

Seeing Brokeback Mountain again in middle age, I’m struck by the film’s understanding of the walls we build around ourselves and those small gestures and mementoes that mean nothing to anyone else but convey a lifetime of emotion for one person—or two. Ennis and Jack found the loves of their lives herding sheep on a mountain in the summer of 1963, and they spent the rest of their days trying to find their way back there.

Jeremy C. Fox